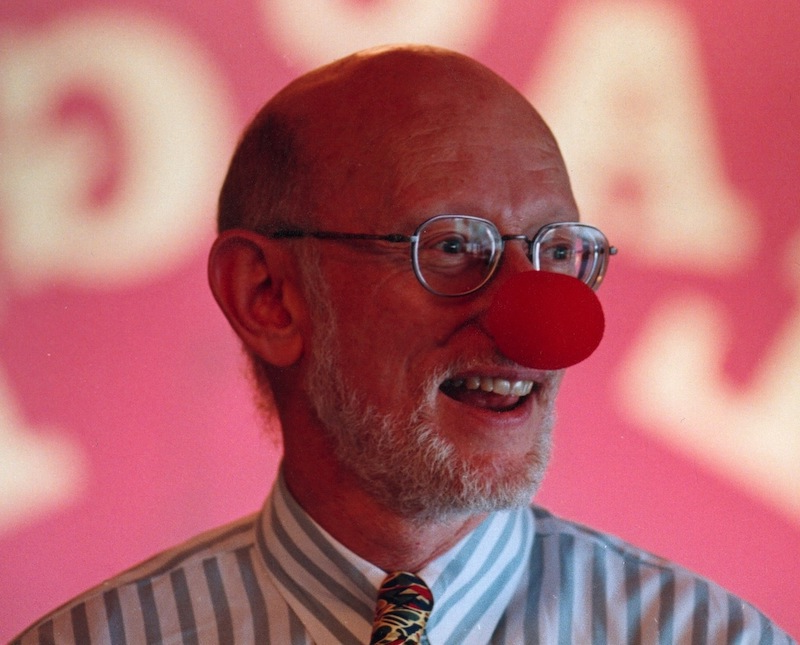

Allen Klein Jollyologist

dr george pollard

Here’s a fact you can’t ignore. All species, save humans, arrive intact, with everything needed to live full, fruitful lives. Only humans arrive lacking a full survival kit. We rely on others; we invent and learn to fulfil our wants and needs.

Think of it this way. An apple pie is circular. Run your index finger along the outer edge of the crust, the rim; it never ends, it’s complete. That’s how your dog or rhinoceros arrives, intact.

Now, imagine a pie, with a large slice missing. Run your index finger along the rim. Sooner than later your finger falls into the empty gap.

That gap is the human dilemma. We’re born with a gap in our survival abilities. Humans struggle to fill the gap, to create what nature doesn’t provide.

We scramble to protect the young, make tools for hunting or war and ideas or rituals to explain bad luck, the weather or death. Our wit emerges, as a latent result. Wit or intelligence forms a mind we use to fill the gap left by nature.

We think of the past and present, as do most animals. We can predict the future, to a degree. This means we can plan for an unknown, volatile tomorrow, if we wish.

Here’s a practical example. Howard Smith is 91 years old, reports Noah Remnick, in the New York “Times.” Smith still shovels the snow in front of his Upper East Side home. His secret, for shovelling snow, without having a heart attack, is thinking and planning for the immediate future.

“What you want to do,” Smith told Remnick, “is mark your line from the top and then scoop it from below. The key is to use a small shovel. I want a safe sidewalk,” says Smith, “not a heart attack.” Salt is his favourite sidewalk garnish.

Smith planned before he began. He didn’t barge out the front door, gripping a huge shovel, ready to dig deep and fast into the snow. Smith used his wit; he readied for the abstract, although near, future and got the best, the safest, result.

Wit has advantages. As foragers, millennia ago, humans thought of the future. When do the tastiest berries grow? Where do those berries grow? Do those berries grow every year, at the same time or not? What animals are edible? How might I track down tasty animals?

Wit has a weakness. Hours or days not spent foraging or hunting, we spent thinking. Will the cave ceiling collapse. Might a large animal have me for lunch? Will rocks slide down the mountain, trapping us in the cave? If so, how might we get out? Could we get out? Why does everybody, in my clan, dislike me? What can I do to make everybody like me? Why does Glog always stare at me?

For the first farmers, thinking of the future was essential. What crops can I grow? What will produce the largest yields for the least effort? Will the weather hold? How can I protect surplus food and, maybe, the women and children, from marauders? Why does everybody in my village dislike me? What can I do to make everybody like me? Why is Isi always staring at me?

Thus, with wit came recognition of doubt that led to apprehension. Eventually, it morphed into worry. Wit, which allowed us to land on the moon, gave us worry about our appearance or abilities.

We believe we survive, best, what we expect. We prepare for problems, likely or imagined, not good times. A newscast mostly reports negative events or outcomes.

There's no sense worrying over good times, which are not much of a threat. Worrying about the future offers greater rewards than not worrying. What disaster might happen to us, we fret, not what benefits might we receive.

A profusion of worry led to anxiety, which often led to anomie. Anomie is a sense of instability or breakdown in society. Anomie may keep us from acting, suitably or not. Anxiety and anomie invade the clever mind. We may seek pills, discounting potential side effects, to ease our mind.

Fortunately, we can adapt to the positive and leave some of the negative behind. That, too, is a result of wit. We can change, if want, if we try.

Attending a talk, given by a motivational speaker, may be a benign way to change for the better. Such speakers “convey information or scenarios that inspire,” says Connor Pierce, a motivational speaker and author of “Transforming Your Life: a step by step guidebook to personal success.”

The goals of such a talk are many. To help us build confidence. To help us let go of anxiety. To help us find a better life. The result is often a more positive outlook and a less nerve-racking life.

Some speakers, such as the late Dr Wayne Dyer, help to improve the lives of individuals. Dyer wanted to inspire women and men to have confidence to change her or his life, for the better. More often, perhaps, the talk focuses on a corporate strategy or vision; here, the goal is to improve morale or cooperation among workers and, eventually, company profit.

A motivational talk may precede an offer to sell books, workshops and so forth. Sometimes you need to be wary what presents as helpful. Somebody is always after your pocket money.

Today, says Connor Pierce, we “are more in touch with emotions.” This is especially true for expressing emotions. Life can seem a series of linked experiences, not isolated incidents; this is good. Motivational talkers can help define and organise life experiences, emotionally.

In business, says, Pierce, companies, today, realise they are not selling only a product, but an experience. Nike moved its focus from shoes and clothing to an experience. Nike created an inspirational slogan, “Just Do It,” as a cue for its new approach.

The Nike model ties seller to buyer on an emotional level. A change in focus and a new slogan reset Nike customer relations. This built brand loyalty. Many companies, worldwide, use the Nike model, today.

Still, individuals as well as businesses need motivation. Speaking to employee groups may pay well, but a wider audience needs to find motivation and inspiration, too, as well as explanations. For that wider audience, humour and laughter may be the way to convert negative into positive.

Humour is the use of words or images to make people laugh or to amuse them. Laughing can build a bridge from speaker to audience, an important tool for inspiring men and women. Laughing feels good, too; we usually want more.

“Laughter is speaking in tongues,” says Robert Provine. It comes from a subconscious response to verbal and silent cues. An unexpected ending to a brief story evokes laughter; so, too, does someone slipping on a banana peel. We can self-induce laughter; this is how laughing clubs often start a session.

Reduced to its most basic sounds, says Provine, laughter is a set of syllables present in every language. The universal syllables are “ho,” “hee” and “haw.” Less emotional than a religious event, perhaps, laughter can be intense, convulsive and reach fever pitch.

Laughter attunes audience attention and reception; a gloomy audience is usually over-critical or indifferent. A laughing audience is eager for what comes next; it might be another reason to laugh and feel good. Learning through laughter is the most lasting way to learn.

Allen Klein, the motivational speaker, bills himself as a “Jollyologist.” He is to talk what Hunter “Patch” Adams is to medicine. “Humour is a tool I use,” says Klein, “that works well.”

Here’s an example. During one talk, a young woman rose to tell Klein of a problem she had at work. After she explained the problem, the audience was silent. Everyone identified with her. A silent seriousness took over the room. Klein asked the woman to repeat what she said and to add “Ha, Ha, Ha,” at the end.

What’s up she wondered? She did as asked. Adding “Ha, Ha, Ha” made her problem seem different, far less serious than she thought and resolvable. The audience laughed, heartily, and applauded, approvingly.

Allen Klein sees himself as an ambassador of life. “My purpose, my passion,” he says, “is to help people lighten up. If this life is the only one we have, we should enjoy ourselves, not knock ourselves over the head; we should be appreciating everything around us.” Never mind those women or men we think don’t like us, focus life around those that show they do like us.

When Sally Field won her second Oscar™, she said, “You really do like me.” It should take two awards to recognise more people like you than don’t like you. That’s life.

“Our lives,” says Klein, “unfold in the stories we tell ourselves.” A dirty look, from a co-worker, during a meeting, may make us think she didn’t like your last e-mail. That’s one story to explain the dirty look.

There are other, equally likely stories for what you think is a dirty look. Your co-worker might be concentrating on the discussion and not, in fact, looking at you. She might be focusing on her daughter, ill and home from school. More simply, she might be hungry, anxious for lunch.

“Lighten up,” says Klein. Don’t settle for the first negative story or explanation, for what happens. Find alternative stories. Maybe seek the truth from the other person.

“I started doing therapeutic humour after my wife died, at age thirty-four,” says Klein. When she died, I knew all I needed of grief. I needed comforting words that spoke to my heart, my soul.”

Klein needed to know how to become happy, again. “Over the past twenty years,” he says, “I expanded beyond humour to include happiness.” Happiness means seeing the world in a lighter way.

His quest is simple. “Happiness is what my most recent book, “You Can’t Ruin my Day: 52 wake-up calls to turn any situation around,” covers,” says Klein. “I see so many miserable people. I want to help them.”

“I guess my quest for a happy world stems from my father. He was a printer, all his life; he loved it. Every Friday he worked late to print a magazine; he didn’t mind. He was happy, all those years I was growing up. He retired at age sixty-five, with a gold watch the company gave him.”

As much as his father loved printing, he focused on a negative part of his job. “My father hated his boss controlling him,” says Klein. “He focused on how much he disliked his boss, not the joy of what he was doing, printing, for a living.”

“I see too many people unhappy at work,” says Klein. “Science shows us chronic unhappiness is not good for our health.” The stress of unhappiness at work, perhaps the most important part of our lives, may be doubly harmful.

The experience of his father suggests unhappiness may result from a lack of autonomy. “Yes, I think so,” says Klein. “I’ve see that lack of control in people around me. It can derail happiness.

It’s not in our stars; it’s in our attitudes. “How we choose to see what’s happening to us or around us is important,” says Klein. “I see people in traffic jams happy, smiling, enjoying what’s on the radio, say. I see other women and men that are angry because they’re stuck in traffic; they slam the steering wheel or dashboard.”

As a boy, Klein saw how well his aunt Jessie handled a stress-filled life. “She was divorced,” he says, “raising two children, on her own, during World War 2. She was working at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Then she was laid off and living on welfare.

“Still, Aunt Jessie was one of the happiest people I have ever known. What I think brought her happiness was doing this or that for others.” This was a diversion, allowing her not to focus on herself or her circumstances.

“If she knew it was someone’s birthday, in her apartment building,” says Klein, “she would immediately bake a batch of cookies and bring it to him or her. If she heard a woman, in her building, was pregnant, she might knit a sweater for the baby. She was always doing something for someone else.

“Aunt Jessie joked around, all the time. She was joyous. She kept her good mood even though she was on welfare, raising two children by herself.”

“Viktor Frankl, the noted psychiatrist, talked of humour in a World War 2 concentration camp,” says Klein. “It’s the last place anyone would expect humour; I don’t know if I find humour in a concentration camp and I’m the Jollyologist. Still, Frankl credits humour with helping him survive.

“Every day,” says Klein, Frankl found something funny. Humour gave Frankl the power to change his attitude. In humour was the power to rise above circumstances that he had no power to control.”

Poet Robert Desnos used humour to postpone execution in a contraction camp, during World War 2. “Susan Griffin told that story,” says Klein. “Desnos and others were on the way to a gas chamber. He jumped out of line and began to read the palm of the woman in front of him. He forecast a long life for her, as she stood in front of the gas chamber. Other prisoners came to life and thrust their palm at Desnos.” He read on.

“The guards became disoriented,” says Klein. “Desnos created a new reality. A routine mission changed, dramatically. The prisoners returned to the barracks. The executions did not go forward.”

Desnos lived to die another day. “He used his imagination to save himself and others,” says Klein. “The humour, the sheer lunacy, of reading palms on the way into a gas chamber altered what seemed a certain destiny for several women and men that day.”

Do we have the ability to change circumstances? “Not all the time,” says Klein, “but many times we can certainly change. We’re not in concentration camps, on our way to a gas chamber for execution. We do have the chance to change less severe circumstances, all the time.”

Is Klein on a mission to reverse part of how our parents raised us? “Yes,” he says, “there’s negativity in our up-bringing. I read research that showed such negativity reaches far back in our history, as a species. In pre-history, we had to be aware of a rockslide or dangerous animals.

“I think, because negativity is largely implanted in us [from birth], we need to give extra energy to counter-acting it.” What Klein tries to do is explain what we need to do to counter-act negativity, why and how. “Not everybody gets it,” he says.

“I try to counter-act negativity in my own life. I get up-set, too. I try to be an example of what I teach.”

Do motivational speakers, their books and workshops, urge us to focus too much, on what we do and how we think? “It’s hard to say, specifically,” says Klein. “When I read a book or go to a lecture, if I can take away one idea, I’m happy. It makes my life better.”

He’s not sure everybody takes away one idea or any ideas. “What I do,” Klein says, “is entertaining and educational.” Audience members may focus on the former at the expense of the latter.

Don’t try to take in everything a speaker or writer suggests. “I focus on one idea,” says Klein, “and I make sure it fits my life. I’m a member of the National Speakers Association (NSA). I learned a great from the NSA, but many of its members are talking to corporations, which doesn’t fit what I do.”

It’s important for the audience members to be selective. “Anyone that listens to a speaker or reads a book needs to take what fits, his or her life, and leave the rest behind. Every point or suggestion doesn’t work for everybody.”

Can a typical woman or man make such selective decisions? “Perhaps not, it’s why this conversation is important. A reader might see how she or he must decide what advice works for him or her and act on it.

“I have a friend that’s going through a major life crisis, right now. The other day, we were talking of the trauma he’s going through. He wanted to visit me, but there was trouble with the airline ticket.

“When we get off the phone, I said, call the airlines and correct the problem.” He called back after he talked with the airline. “He said all was now well,” says Klein, “he knew how much it would cost, how he might cancel the ticket, if necessary, and so forth.

“After the second conversation, I realised our first chat focused on what he could not do.” Distress was in his way; he was, perhaps, a little confused. “Our second chat focused on what he did to solve his problems with the airline.”

“My point is he needed a pat on the back. He needed to pat himself on the back. He needed encouragement, a boost of confidence.

“He had a problem. He took timely action to fix the problem, in the midst of all his difficulties. Now, he felt a great deal better,” says Klein. Everybody can do what his friend did; that is, take charge.

Klein thinks we don’t accept ourselves, enough. “We focus too much on our problems, the negative, which is a word I don’t like, in our lives. We need to focus on what is right in our lives; what we can make right, with a little thought.”

Maybe we focus too much on the irrelevant parts of our lives, not the relevant. “Could be,” says Klein. The point is there’s usually more positive than negative in our lives, which we don’t recognise. The old song reminds you to “Count Your Blessings.”

Is motivational or inspiration speaking prescriptive? Some listeners or readers can cherry-pick advice that helps them. Most can’t or so it seems. These women and men go to a talk or read book expecting a ready-made life plan handed to her or him.

“Well, it could be,” says Klein. “I don’t want readers to pour over my every page or word. If she or he opens my book and reads whatever passage pops up for that a day, that would be fine. Do whatever I suggest, on that page or in that section. Tomorrow, repeat the random opening of my book. He or she might go to the index to choose, say, keeping it light, and work on that.

“Sometimes, I’m not prescriptive enough. A reader buys my books to help his or her life; I must be prescriptive, to some extent. Too prescriptive, I don’t think so, unless the reader happens to be obsessive compulsive.

“I don’t expect readers to use every iota of advice I offer. I write of what I do. If readers did all I suggest in my books, he or she would be me. I’m not sure if that’s what I want or they need.”

“Life is analogous to a joke,” says Klein. “That doesn’t mean life is a joke, though. An elderly woman, living in a nursing home, raised her cane in her left hand and said, ‘I’ll have sex with any man that can tell me what I’m holding in my hand.’ A man across the room yells, ‘An elephant.’ The woman says, ‘Close enough, you win.’

“At the beginning of the any joke,” says Klein, “you are given a story, statement or question.” Say, two men are drinking in a pub. “At some point in the joke, the story, statement or question, turns into something you didn’t expect.” The two men start talking of mothers-in-law. “You feel duped or surprised,” says Klein, “and you laugh.” One fellow says, “I’m lucky. My mother-in-law is heavenly.” The second fellow says, “Yes, you are lucky. My mother-in-law is still alive.” *

“Life is like the structure of the joke. Life punches you.” You lock your keys in the car or receive a speeding ticket. “Then you must decide to see the punch as positive or negative,” says Klein. Someone said it is how hard you can get hit and still get up, again, not only if you can get up.

His motivation for “You Can’t Ruin My Day,” was receiving a speeding ticket. As the constable wrote the citation, Klein thought of how he could make this a positive experience; he came up with an idea for a new book. I dedicated my last book, “You Can’t Ruin My Day,” to the police officer that cited me for speeding.”

Laughter lightens the load. The absurdity in the mother-in-law joke, above, distracts, if briefly. After a laugh, problems may not seem as burdensome.

Klein parses the word, laugh, letter by letter, to great effect. “I’ve been using this breakdown of the word, laugh, for over twenty years. All that I do, books, talks and workshops, is based on those five letters, l-a-u-g-h.

“‘L’ is for let go. Holding on to anything we can’t laugh about, such as anger, frustration or anxiety, is negative.” It’s hard to let go of negative emotions. “Still, we need to laugh about the negative,” says Klein, “to rid ourselves of it and the associated stress.”

To make this point, Klein uses a story of two monks walking down a wooded pathway, which ran along a stream. “They came upon a woman having difficulty crossing the stream,” he says. “One monk stepped off the path, picked up the woman, carried her across the stream, put her down and rejoined his friend.

“A mile or so down further into their walk, one monk expressed his dismay at how his friend had helped the woman across the stream. He said, 'We are celibate. We are not supposed to even look at a woman, let alone pick one up and carry her across a stream.’

“The second monk said, ‘I put the woman down a mile back. Are you still carrying her around?’” Letting go of what irritates us isn’t easy, but is essential.

“The ‘A,’ in laugh, is for attitude. We have the power, the ability, to change our attitudes.” That’s what “You Can’t Ruin My Day,” his last book, is about. “You can’t let anyone take away the power you have to change your attitudes,” says Klein.

“Change your attitude toward whatever you find makes you angry or upsetting. Then your life will be better. You’ll be happy.

“For the letter, ‘U,’ I had to cheat a bit,” says Klein. “I couldn’t find a word, beginning with the letter ‘U’ that satisfied me. I changed it to ‘YOU’ because I realised I can’t change the life of anyone else; he or she must change or let go for themselves, no one else can do it for them.

“‘G’ is to go do it, make the necessary changes in your life. There are all kinds of ways to get more laughter and happiness in your life. My first book, “The Healing Power of Humour,” offers fourteen ways to bring more laughter and happiness into your life, such as having toys around, watching how children lighten up and so forth.”

Klein offers a story about letting go of frustration. A young, cocky construction worker always bragged of his strength. He badgered older workers, especially, with his claims of unusual strength. One day, an older worker confronted the braggart.

Said the older worker, “I’ll bet you a week’s pay I can haul something, in this wheelbarrow, over to that building, which you can’t bring back.” “You’re on said the braggart.” Picking up the handles of the wheelbarrow, the older worker said to the braggart, “Get in.” Frustration let go through imagination and humour.

“Finally, the ‘H’ is for opening your humour ears and your humour eyes. I cheated, with the ‘H.’ Humour is all around us, almost all the time.

“I was in a laundromat, one day,” says Klein. “I looked on the wall. A sign read, ‘When the washer stops, remove all your clothing.’ I did.”

Jo-Anne Bachorowski and her co-researchers found eighty per cent of laughter occurs in every day contacts among women and men. Only twenty per cent of laughter occurs, formally, such as in a comedy club or while watching a sitcom on television. Further, laughter mostly occurs at the end of a phrase, acting as punctuation, of a sort.

Casual conversations and jokes take similar forms. There's a setup, maybe some expansion and a point- or punch-line. “Hey,” says one fellow to another, in a joke by the late David Brenner, “do you remember when total recall meant you had a great memory?” “Sure,” says the second fellow. “Last week, General Motors had a total recall of all the cars it made, in the past ten years.” “Wow,” says the second fellow. “Yea, there was a problem with the brakes. When you pushed on the brake pedal, the car did not stop.”

Workplace advice or help is a large part of what Klein does. “The same l-a-u-g-h applies. What are workers holding on to; what won’t they let go? What are their stresses?

“For hospital workers, insufficient parking space is a major compliant,” says Klein. “They say, ‘I have to walk a mile from my car to my office.’ How can they let go of such problems and change attitudes? I try to find the positives in the problems.”

What’s positive in needing to walk a mile from car to office? “Well, you’re getting some exercise, more fresh air, maybe meeting co-workers and so forth. I focus on the positive, not the negative, the benefits, not the costs.

“I go through the l-a-u-g-h, focusing on the problems the workers, the audience, express. How can workers rise above circumstances and take back the power. Ideally, they find something humorous about the problem.

“To find humour, in a problem at work, I exaggerate. Can you overstate your car being a mile away from your office? Of course, you can. We use play to find the funny in most any circumstance.”

Someone might exaggerate the negative and it becomes funny. “Yes,” says Klein, “something along the line of ‘My car is so far away from office, I had to ask my boss to carry me, the whole way. It turns out she carried me to the wrong car. She had to carry me a mile in the other direction.’

“See what happens. You’re laughing at something that stressed you out.” The stress subsides. “In context,” says Klein, “most every set of circumstances is funny, somehow, someway.”

Norman Cousins edited “Saturday Review,” an influential magazine, in the middle twentieth century. After a trip to Russia, in 1964, Cousins fell mysteriously ill. The diagnosis was Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS), a painful, incurable disease of the spinal column, which robbed him of full use of his limbs. Those with AS endure relentless pain and sleeplessness.

Ankylosing Spondylitis is usually fatal and in a short order. Rather than take medication, which could only ease his pain, Cousins took control of his treatment. First, he checked out of the hospital and into a hotel.

Cousins arranged for large doses of Vitamin C and laetrile, which did little to ease the pain. He also amassed all the funny material, movies and books, he could find; he even wrote his own jokes. He found a ten-minute laugh, hearty and deep, even if forced, gave him two hours of sleep, uninterrupted by pain.

During his waking hours, Cousins laughed and laughed and laughed. After a month, he returned to the hospital for a routine check of the Ankylosing Spondylitis. Tests showed no sign of the AS remained.

Laughter was the best medicine. For Cousins, it led to a spontaneous remission of a deadly disease. In six months, he regained used of his arms and legs; in less than two years he was back at “Saturday Review.”

His ability to promote his recovery evoked much scientific interest in the healing power of laughter. For a time, Cousins was an Adjunct Professor of Medical Humanities for the School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, for his important work in area of laughter and health. Shortly before his death, in 1990, he received the Albert Schweitzer Prize for exemplary contributions to humanity.

How does Klein use l-a-u-g-h for healing? “It may seem ludicrous, putting loss and laughter in the same sentence. Yet, it works.”

Keltner and Bonanno studied laughter as a way to cope, with life. “The more widows and widowers laughed, in the early months after their loss,” Klein says, “the better their mental health over the first two years of bereavement.” Other studies confirm Keltner and Bonanno. “Laughter is a great coping mechanism.

“I’m a certified laugh leader,” says Klein. “I’m a trained in laugh therapy. I learned how to make people laugh.

“There are laughing groups all over the country. Such groups started in India. There several laugh groups in Canada.”

People, in laughing groups, start to laugh for no reason except to laugh. “Yes, women and men get together to laugh. There are no jokes, they simply laugh. Often, they force themselves to start laughing.” Then the laughter consumes them.

There are physical responses to laughter. “When we’re laughing, even false laughter, we may ease congestion in the lungs,” says Klein. “The lungs fill with deep breathe; get more oxygen. Laughing relaxes us.

“Dr Lee Berk, at Loma Linda University, showed that cortisol, an immune suppressant, is reduced in our bodies, when we’re laughing. Immune boosting chemicals are also present in larger amounts, when we laugh. It’s physically good for us to laugh,” says Klein. Laughing is healthy, thus most of us want to laugh all we can.

Even a forced laugh is helpful. “Yes, that’s what the laughter clubs do. The laughing starts slowly and builds. Everyone feels good and forgets their stress; some of the physical benefits, I mentioned, also happen.”

No one overdosed on laughter. “I love people that make me laugh,” said actor Audrey Hepburn. “I honestly think it’s the thing I like most, to laugh. It cures a multitude of ills. It’s probably the most important thing in a person.”

Losing a job or losing a loved one is a part of life, as is grieving the loss. Is laughter useful for dealing with grief or loss? “Of course,” says Klein, “it is coping. After a loss, we need to learn to let go, of the loss, and go on living; laughter helps a great deal. Laughter lets us step back from a loss and its effect.

“During loss, there are many tears. During hearty laughter, there can be many tears, too. These tears are cleansing.”

“One researcher found tears produced when peeling an onion contain no toxins. Yet, when we laugh, heartily, there are toxins in those tears. The same goes for tears of grief. Emotional tears, from laughter or crying improve health, in some way.” Tears of joy and laughter are healthy.

Laughter is not a cure-all, but a lasting way to ease your mind. The end of life is no laughing matter. Still, laughter allows us a moment of diversion and the promises of hope; without hope, there is nothing.

“Losing a loved one is not easy,” says Klein. He lost his wife, to cancer. That loss affected his life, most of all.

“The end of life may be the most stressful time,” says Klein. First, shock sets in followed by pain and stress. What will I do without this person in my life?

“Loss hurts,” says Klein, “there’s no denying it. Still, loss can help us become wiser and stronger.” Once we accept the loss of a loved one, it can help us appreciate life even more.

Three questions are important after the loss of a loved one. First, says Klein, ask how the loss will help you live a fuller life. Second, how does the loss help you contribute to a greater good for all? Third, ask if the experience of this loss will make you a more loving person, if so, how.

“Endings are beginnings, too,” says Klein. When he wife passed away, he had no idea where life would take him. “I had to trust.” First, he did hospice work. Then he discovered the therapeutic uses of laughter and humour. “Looking back,” he says, “I was shown that out of death comes a new life.”

Today, Klein shows “how laughter is a good way to relieve much end of life stress, improve oxygen flow and general well-being. This applies to the dying, survivors and caregivers, alike.

“I talk to many hospice workers,” says Klein; humour and laughter are big part of their working lives. “I’ve been to a number of hospice facilitates that I’d want to move into. In one hospice, the wall of the room opened up, the staff could wheel the patient onto a fresh-air veranda. Another hospice, in horse country, allowed the patient to have his or her horse in an adjacent enclosure.

“Hospices, today, have beautifully decorated rooms and areas, with vivid colours and art work.” There are family rooms; sitting rooms, with large fireplaces. One hospice Klein visited makes a harpist available, as wished. Klein says these are no longer gloomy places.

“There’s a hospice in Honolulu, which is most remarkable. It was built with community funds.” The nursing station is in the centre, surrounded by rooms; the image is of a spoked wheel, no patient is ever far away.

“When I was a hospice volunteer, years ago,” says Klein, “I learned so much from each patient.” He goes to staff meetings, today, at various hospices. “The laughter, the level of humour, is incredible. Laughter is a coping mechanism for everyone.”

Currently, Klein devotes more time to writing than to speaking. “I realised I can reach many more women and men, with one book,” he says, “than in a lifetime of speaking or holding workshops.

“Now that I have a deadline for my next book, I write every day. I started at 9 am, today, taking only a break to talk with you. Later, I’ll walk my dog, Cheerios, and I have a show to give this evening.

A writing routine is important for Klein. “I try to write all morning,” he says. “I walk Cheerios at a certain time. I eat at a certain time and so forth.

He tries not to mix writing with researching and editing. “Later in the day, as I can, I return to working. Sometimes, though, I have talks to give, in the evening, which limits my writing for that day.

“When I can return to my work, in the evening, say, this is when I try to research or edit.” Yet, when an idea hits, says Klein, “I must run to write it down, any time of day. When an idea arrives, I must take it.” Good writers are slaves to ideas.

Writing, for Klein, is akin to playing a musical instrument. Although he doesn’t play piano, he says, “Writing is like practicing piano, I think. The more I write, the more I’m ready for ideas to strike.” Practise makes perfect.

“What I also notice,” says Klein, “is the more I write the more often good ideas come to me. It’s remarkable. I put silent feelers out about what I want to write. Suddenly, ideas come to me.” This might be a form of automatic writing.

His daily writing target stems from his book contacts. “Right now,” says Klein, “I’m contracted to provide a 65,000 word book.” This means he needs to write roughly one thousand words a day, until deadline. “I don’t count the words, as I write,” says Klein. “I realise I must come up with so many words in the timeline to which I’m contracted,” but he doesn’t obsess over daily targets.

“Loosely, my target is several pages each day,” says Klein. “If I met that goal, I know the book will complete by the deadline. Thus, it’s not the amount of words or page, it to keep writing at a steady pace.”

As well as Cheerios, does anyone inspire Klein to write? “I don’t know if it’s “who” inspires me or not. Getting up in years, as I have, I want to leave a legacy. I guess other people, today and in the future, drive me to get my words, my thoughts, out before I’m gone. I want to help future generations, too.”

Laughter is no laughing matter. Allen Klein confirms the truth of such clichés, as he helps women and men let go of the negative and increase their grip on the positive parts of life. Laughter is the best medicine, too, as Norman Cousins confirmed.

Klein reminds us that despite naysayers and negativity, we’re ears deep in positive. There are remarkable sunrises and astounding sunsets. Most of us first learned to focus on bad weather, the negative, not good weather, the positive.

Breaking the pattern of negativity, finding a balance, at least, of positive and negative, is difficult. What we learn early in life is hardest to escape, later. Klein gives everybody the tools to become a social Houdini, to break free of old chains. Freedom and happiness travel together.

Klein doesn’t provide a one size for all solution; there are no cookie-cutter ways to a better life. Klein offers a wide swathe of helpful choices, mostly based in laughter. After the laughter, it’s up to each member of the audience to decide what works for him or her and to leave the rest behind.

Selecting what works, from the offerings by Klein, is hard. “Do this or that for a better life,” says Klein, but we’re mostly arrogant, reluctant to take advice. It’s easier, more convenient, to want the complete package, “We’re all born lazy,” Jack McLaughlin, one of my teachers at business school, all those years ago, used to say. “Damn few of us change.”

As children and young adults, we heard, with certainty, the rhythm of life; we appreciated sunrises and sets, rain on the roof, even silence. Suddenly, as adults, we’re busy with family and careers. A lifestyle maintenance mode consumes us and deadens the sounds of life. Klein offers to help us back into the joyful rhythms of life. That is, happiness, laughter and freedom.

Allen Klein is not a comedian, in the usual way. Still, his audiences roar with hearty laughter. All he needs to do is to show our superiority over most circumstances or the incongruity inherent in many problems for his audiences to laugh in recognition. Most of his humour also helps us release tension and stress built over years of focusing on the negative.

Klein asks the members of his audiences to stop for a think. We stop for a lunch or to go to the bathroom, why can’t we stop for a think. The philosopher Georg Hegel asked much the same question, two hundred years ago.

Problems can hide benefits. A long walk, from car to office, is exercise in the fresh air. The long walk back, from office to car, is a chance to unwind, let go of the workday. It’s a matter of stopping to think of what stifles us and how we can rid ourselves of it.

Resistance to letting go, to seeing a problem in a new, clear light, is more draining than the problem, itself. That’s the rub. Attitude, more than problem, holds us back and saps us of energy better used to make our lives happier.

Some women or men won’t benefit from Allen Klein. Humour does not drive everybody; not everybody is seeking or accepting of humour. Motivational speakers take a wide variety of approaches; there’s one or ten to suit all preferences, an inspirational speaker for everybody. Allen Klein is the funny one.

Allen Klein aims to partially fill the gap nature gifted us at birth. At first, the gap usually fills with a focus on the negative. Klein tries to at least balance positive and negative, ideally giving an edge to the positive.

-----

*Taken from Ruth Nemzoff (2008), “Don’t Roll Your Eyes: making in-laws into family,” published by St Martin’s Griffin.

Jean M Auel (1980), “The Clan of the Cave Bear,” published by Crown.

Bachorowski, J.-A., Smoski, M.J., & Owren, M J (2001), “The acoustic features of human laughter,” published in the “Journal of the Acoustical Society of America,” volume 110.

Susan Griffin (1996), “Whole Earth Review.” Spring edition. The execution of Robert Desnos took place in Theresienstadt Concentration Camp, Czech Republic, on 8 June 1945.

Dacher Keltner and George Bonanno (1997), “A Study of Laughter and Dissociation,” in Interpersonal Relations and Group Process: 73, 4, pp. 687-702.

Allen Klein (2015), “You Can’t Ruin My Day: 52 wake-up calls to turn any situation around,” published by Viva Editions.

----- (2011), “Learning to Laugh When You Feel like Crying: embracing life after loss,” published by Goodman Beck.

----- (1989), “The Healing Power of Humor,” published by Tarcher Putnam

Robert Provine (2014), “The Science of Laughter,” "Psychology Today."

Noah Remnick (2016), “At 91, Offering Tips on Shoveling Snow,” on the New York “Times” web site 23 January.

dr george pollard is a Sociometrician and Social Psychologist at Carleton University, in Ottawa, where he currently conducts research and seminars on "Media and Truth," Social Psychology of Pop Culture and Entertainment as well as umbrella repair.

- Jerry Williams

- High Noon in New Bern

- Howard Lapides Redux

- Stoking the Imagination

- Johnny Carson

- Sweet Little Lies

- David Rich

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- All the Rage

- Goodbye Parks

- Binding Our Grandchildren

- Sjef Frenken

- Stereotyping

- Democracy Covered

- How Do You Say

- Jennifer Flaten

- De-christmasing

- Food for Thought

- VIP Treatment

- M Alan Roberts

- Rat Racing

- Cries of Rebellion

- Nude Angels

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Obsessive Cat Disorder

- Defensive Driving

- Orange Is the New White

- Streeter Click

- Tanna Frederick

- Dr John Rawls

- Grub Street Philosophy: 1

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- Go Climb a Tree

- Schrodinger’s President

- No Small Parts

- M Adam Roberts

- Choose Life

- Is She the One?

- The Secret

- Ricardo Teixeira

- There is a Light

- The Unicorn

- Monkey Business