Phil Spector

Jennifer Flaten

"In 1958, I worked for McKay Record Distributors, which handled Dore Records in Canada," says Stan Klees, co-founder of 'RPM Music Weekly,' with Walt Grealis. "One day I was sent to the CBC Television studios in midtown Toronto, at Yonge and Summerhill streets. There was a huge problem.

"That studio," says Klees, "deserves a momentary diversion. Originally, it was new-car showroom for the Pierce-Arrow. The Pierce-Arrow was an expensive, luxurious car, made in Buffalo, New York, from 1903 to 1938, and imported to Canada.

"'Cross-Canada Hit Parade' originated from the Pierce-Arrow Studio. It was the number two show on Canadian television, at the time, hosted by Wally Koster and Phyllis Marshall. The show was a big deal for CBC and every problem serious.

"On each show, an international star, such as Bobby Darin, appeared. An American group, the 'Teddy Bears,' was booked, on 'Cross-Canada Hit Parade,' for this particular week. The group had a huge hit on Dore Records, a subsidiary of ERA Records, which McKay Records distributed. I was thus involved.

"'To Know Him is to Love Him,' by the 'Teddy Bears,' was the top selling record of 1958," says Klees. "Recorded for $75, the record took a while to get radio airplay. Once radio found "To Know Him," it became a huge hit.

"The group walked out during rehearsals for 'Cross-Canada Hit Parade.' They came and left, a producer told me. Their manager became angry. It was unclear why. They went back to the hotel.

"This is when I became involved," says Klees. "I asked for the name of the manager and headed off to their hotel. CBC always put guests up in the Westbury, which wasn't far from the studio. I thought I should introduce myself as my assignment, at the time, was to represent their record label, Dore, which McKay Records distributed in Canada.

"I phoned their suite from the lobby. An obviously young man answered. He yelled across the room, presumably to their manager, 'Some guy, in the lobby; he wants to talk with you.'

"The manger, of the 'Teddy Bears,' took the phone. She says, 'Who are you? What do you want?'

"I explained I was with their record company. I wanted to meet her and them. Could I buy her a coffee? She told me to wait in the lobby.

"In minutes," says Klees, "the elevator doors opened and two teenage males walked across the lobby, spotted me and went to the house phone. I guessed they called their suite to report that I didn't appear diabolical.

"A few minutes later, a woman exits an elevator and walks briskly across the lobby, right up to me. The two teenagers, who scouted me, joined us. It wasn't hard to guess she was the manager of the 'Teddy Bears.'

"She says, 'I'm very upset with those people at the CBC. I had no choice but to pull the act from the show. What are you going to do?'

"My thinking," says Klees, "was this is a woman with whom you can't disagree. I don't much care for CBC, either, I said. CBC treats people poorly, with little respect. CBC is a clique.

"She mellowed on the spot. The two teenagers, who had returned with her, stood, watched and listened. I was making points.

"We walked into the coffee shop, of the Westbury. The young men took their own table. The problems, I heard, lay partly with CBC.

"The group, the 'Teddy Bears,' was a trio, two teenage boys and a girl. Over coffee, their manager told me she didn't like what the CBC hairstylist was doing. We found a way around that problem.

"The larger issue, the manager eventually admitted, was the group members were getting too friendly, with each other. Chaperoning three teenagers, on the road, was making her a wreck. I don't know how she solved this problem, but the group broke up not long afterward.

"A few years later, in 1964, I owned Red Leaf Records. Bob Crewe, the producer behind the 'Four Seasons,' wanted to record two of my acts, at Atlantic Studios, in New York City. The two acts were Shirley Matthews and Phil Gariepy; he's best known as Jayson King. A highly successful engineer, Tom Dowd, oversaw the sessions.

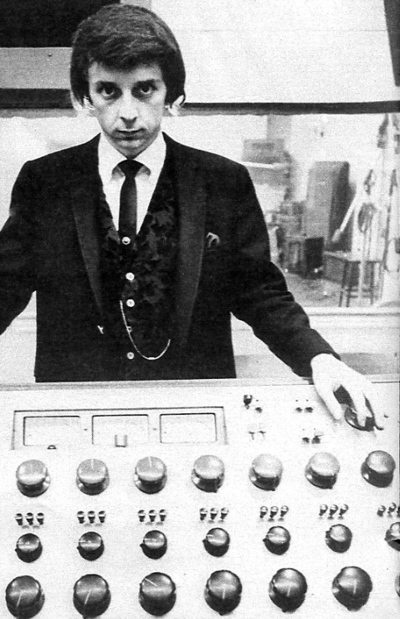

"During one recording session, in New York City, I talked with Harriet Wasser. Hesh, everyone knew Wasser as Hesh, was personal assistant to Bobby Darin. I asked Hesh to whom Crewe was talking; I thought I knew him from somewhere. She said that was record producer, Phil Spector.

"Spector, along with Marshall Lieb and Annette Kleinbard were the 'Teddy Bears.' Of course, I realized, I met Spector at the Westbury, in 1958. Hesh reintroduced me to him."

Spector 1958, 1964 and 2009

As a pop record producer, Phil Spector ranks among the best. He created the most heard record, ever, "You Lost that Lovin' Feeling." The record is also the high point of the Wall of Sound style he created.

In 2009, Spector became a permanent tenant in a California State Prison. A jury found him guilty of second-degree murder, in the 2003 shooting death of actor Lana Clarkson. The sentence, for the then 69 year-old Spector, was 19 years to life.

Those who know Spector, agree he's fickle and creative, but not a murderer. He claims Clarkson, dysphoic following a breakup, accidentally committed suicide when kissing his gun. Some women say he held them at gunpoint when they wanted to leave his home.

Many think the traits that made Spector a top record producer led to his bizarre actions, after his fame lapsed. Sir George Martin, who produced "The Beatles," has yet to murder anyone. Mutt Lange, who produced "Def Leppard," Bryn Adams and Shania Twain, among others, has failed to commit a capital crime. A causal link between producing hit records and murder seems frail.

Born Tuesday 26 December 1939, Harvey Philip Spector grew up in Bronx, New York. When his grandfather immigrated to the USA, he changed the spelling, of the family name, from Spekter to Spector. In 1949, his father committed suicide; his mother moved the family to Los Angeles, in 1953, for a fresh start.

Spector attended Fairfax High School, in West Hollywood. His classmates included record producer and talent manger, Lou Adler, and Bruce Johnson, a songwriter and member of the "Beach Boys," as well as session musicians Steve Douglas and Sandy Nelson.

Spector found solace in music. He always loved music and had a talent for it. He played guitar, piano, bass, drums and French horn, with equal ease.

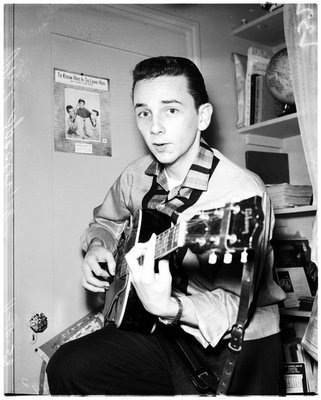

After learning to play guitar, Spector entered for a school talent show. He performed a Lonnie Donegan song, "Rock Island Line." A skiffle song, "Rock Island Line" topped the charts in the UK at the time.

Skiffle, slang for a rent party, likely began in New Orleans, after the US Civil War. The music combines early forms country, jazz and blues music styles. Skiffle instruments, usually home-made, include jugs, musical saws, cigar-box fiddles, paper kazoos and washboards.

In the 1930s, skiffle was a euphemism for Country Blues. Ma Rainey, an early Blues singer, who influenced Bessie Smith and Janis Joplin, called her music skiffle. Zeke Manners, a Los Angeles disc jockey, was popular, in the 1930s and 1940s, as a non-Blues skiffle performer.

Following World War 2, skiffle vanished from the USA and Canada. The music style remained important and influential in the UK. As teenagers, George Harrison and John Lennon were in skiffle bands.

The first public show, by Spector, was novel. He took his West Hollywood audience, mostly unaware of skiffle or blues, into a new musical world. A year or two later, White singers, such as Pat Boone, would top sales charts, covering blues songs by Black singers, such as Fats Domino.

In 1954, the "Crew Cuts," from Toronto, boldly covered "Sh-Boom," while it was an R&B and "Hot 100" hit for the "Chords." A great many radio stations refused to air any record by a Black group. The "Crew Cuts," a white-bread creation, if there was one, had a ready market.

Boone cagily covered Domino on "Ain't that a Shame." Presley covered Little Richard on an old blues standard, "Lawdy Miss Clawdy." Brian Wilson, of the "Beach Boys," deftly lifted "Little Sweet Sixteen," by Chuck Berry, note for note, for "Surfin' USA"; Berry sued for credit and royalties, but Wilson got collaborator billing.

Flagrant theft is the only way to describe white-bread covers of Black music, in the 1950s. Most often, the White singer had the bigger hit, because of more and better production and promotion of their recording, with royalties to match. Black musicians were fortunate to get a box lunch, a bottle of tenth-rate hooch and a few dollars.

A mostly White owned and controlled industry exploited mostly Black performers: Karl Marx knew it inescapable. Decades passed before Black musicians got their due, many passed away, unrecognized and unpaid. Chuck Berry, the King of Rock and Roll, has a right to anger, although he benefited more than most.

Spector didn't want to exploit anyone. He wanted to try something new for his audience and did. His innovation, offering new music to an audience, is most important.

After graduating high school, in 1958, Spector formed "The Teddy Bears," with Marshall Lieb and Annette Kleinbard, a friend of his girlfriend, at the time; Kleinbard later changed her name to Carol Connor and wrote several hit songs. Sandy Nelson was a last-minute addition as drummer.

Spector wanted to record, more than to perform. Inspired by the epitaph on the gravestone of his father, Spector wrote, "To Know Him is to Love Him"; he also wrote, "Don't Your Worry, Little Pet," so the group would have two sides for a single 45-rpm record. By this time, Stan Ross, co-owner of Gold Star Studios, was tutoring Spector on how to produce records.

Spector, Lieb and Kleinbard came up with $75 to record the two songs Spector wrote. He took their tape to his neighbour, Lew Bedell, co-founder of ERA Records and owner of Dore Records. Bedell like their music and signed "The Teddy Bears" to a four-record deal.

After a slow start, radio noticed "To Know Him," the B-side. The song topped the "Billboard Magazine Hot 100" and sold one million singles. The group appeared on "Bandstand," with Dick Clark, and the "Perry Como Show."

The four-record deal, with Dore, dwindled to one; there were many disagreements over money. Follow-up singles and an album, both on Imperial Records, barely charted. "The Teddy Bears" disbanded in late 1959. Spector, who suffered extreme stage fright, enrolled at UCLA, then moved back to New York City, shifting his focus to songwriting and producing.

While recording an album, with "The Teddy Bears," Spector met record executive Lester Sill and songwriter Lee Hazelwood. Sill, at one point, headed Colpix Records and Colgems Records. Hazelwood wrote, "These Boots are Made for Walking," for Nancy Sinatra, among other hits.

Sill also managed the songwriting team of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. They wrote "Hound Dog" and "Jailhouse Rock" for Presley, "Ruby Baby" for Dion Dimucci as well as the R&B standard, "Kansas City." Other hits they wrote include, "There Goes My Baby," "Yakety Yak," "Poison Ivy," "Charlie Brown," "Love Potion Number 9," On Broadway," "Spanish Harlem" and "Stand by Me."

Spector fell into the best company possible when he met Sill and Hazelwood. Hit records don't happen. Expert songwriting, recording and promotional skills blend into a hit record.

Sill and Hazelwood were the best makers of hit records, at the time. Both knew how to encourage songwriters. Hazelwood knew how to get the most out of a recording session. Lester Sill knew how to promote a hit record.

Spector dove into production. In Phoenix, Arizona, Lee Hazelwood was recording a new act, "Duane Eddy and the Rebels." Spector learned much, watching Hazelwood coax a top-five debut album, "Have Guitar Will Travel," from a nervous band.

In 1960, Spector took a job at Hill and Range, the music publishers, in New York City. He worked as a songwriter, talent scout, record producer and engineer. The job rounded out his training.

Lester Sill and Spector founded Philles Records, in 1961. The company name came from their first names, Phil and Les. Spector was fast tracking to success.

The first act signed to Philles Records was the "Crystals." Between 1961 and 1964, Spector co-wrote and produced hit singles for the "Crystals," such as "Uptown," "Da Doo Ron Ron (When He Walked Me Home)" and "Then He Kissed Me." As Kasey Kasem might say, 'this made the "Crystals" one of the defining all-girl groups of the Rock Era.'

Credit often goes to the "Crystals" for an important hit record that it did not record, until much later. Written by Gene Pitney, "He's a Rebel" was for the "Shirelles." Seemingly, Vicki Carr wanted to record the song, too.

The recording, of "Rebel," caused much chaos. Spector wanted "Rebel" out first and on Philles. He rushed singer Darlene Love and a backup group, the "Blossoms," into a studio to record the song.

Hours later, Philles had a hit record. There was a huge sense of relief. Spector, however, gave credit, for "Rebel" to the "Crystals," not the "Blossoms," by mistake or design.

Confusion reigned. Lester Sill and Spector had parted company, by this point. The absence of a seasoned record executive may have contributed to the morass.

Some in-the-know disc jockeys, especially in New York City, gave the "Blossoms" credit. This furthered the confusion. Still, "He's a Rebel" sold fast and well, by 3 November 1962 it topped the "Billboard Magazine Hot 100.'

The "Crystals" rehearsed, tirelessly, to work "Rebel" into its repertoire. Along the way, 15 year-old Dolores Brooks began singing lead for "Rebel" and the next single, "Then He Kissed Me." Good often comes from bad and such luck is serendipity.

Spector produced a different style hit record for Ray Peterson, on Dunes Records. The song, "Tell Laura I Love Her," is a teen-tragedy that countered the optimism of "Da Doo Ron Ron," for example. Spector and Peterson teamed on another huge hit, "Corrine, Corrine," a dramatic ballad. Peterson faded from fame after his second hit.

While working with Peterson, Spector co-wrote, with Jerry Leiber, "Spanish Harlem," a huge hit for Ben E. King. He also did session work, most notably the guitar solo on "Under the Boardwalk," by the "Drifters." Spector produced the original version of "Twist and Shout," by the "Top Notes," the song was a hit for "The Beatles," too.

Back in Los Angeles, Spector produced the "Paris Sisters," an act managed by Lester Sill. After Liberty Records and Capital Record passed their "Be My Boy," Sill, with Lee Hazelwood, formed Gregmark Records to release the song; it bombed. A second Spector production, for the "Paris Sisters," "I Love How You Love Me," was a top ten hit and, today, a pop standard of the Rock Era.

Spector had a magic touch. More than six top ten hit records in three years got him noticed. Spector joined Atlantic Records, in New York City, as a freelance producer.

Songwriters from the Trio Music, in the Brill Building, and Aldon Music, at 1650 Broadway, were his favourites. These stables of writers included, Carole King, Gerry Coffin, Ellie Greenwich, Jeff Barry, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil. This was the Tin Pan Alley of formulaic pop music.

Spector mostly left the session musicians alone. He relied on "The Wrecking Crew," comprised of Leon Russell, Glen Campbell, Roy Caton, Hal Blain and Steve Douglas, among others. Jack Nietzsche arranged the music. Sonny Bono oversaw the studio work.

By 1964, Spector had an assembly line. His success inspired songwriters, many who shared credit and royalties with him. Nietzsche arranged the music for "The Wrecking Crew" to perform under the watchful ear of Bono.

Working with Spector was difficult or maybe near impossible. Yet, he made everybody much money. Putting up with his oddities was part of the job.

Philles hits had a similar sound. This was no surprise, given the approach and traditional ways of making pop music: the next hit must sound as the last. To an outsider, the Wall of Sound, devised by Spector, was an act of genius.

Wall of Sound is a recording method. The sound is dense and layer, with much "reverberation" as well as lush, ornate and orchestral. "Born to Run," by Bruce Springsteen is a good example of the method.

Density stems from using many musicians. A typical hit recording, in 1964, might use two guitars, drums, bass and, maybe, a piano or organ. It wasn't unusual for Spector to use 30 musicians, including woodwind, string and brass sections; for example, "You Lost that Lovin' Feeling."

Layering came from doubling or tripling instruments, say, guitars, bassoons, wedding bells and the vocals, playing in unison. This made the sound fuller. On "Born to Run," 30 guitar-tracks layered over one another.

On his web site, songwriter Jeff Barry describes the Wall of Sound formula. "You're going to have four or five guitars line up, gut-string guitars, and they're going to follow the chords; two basses in fifths, with the same type of line, and strings; six or seven horns, adding the little punches ... formula percussion instruments [such as] shakers [and] tambourines. Phil used his own [method] for echo and some overtone arrangements, with the strings." These were the basic parts.

Spector referred to his pop records, such as "Be My Baby," by the "Ronettes," as little symphonies. Each had a Wagnerian quality, for example, "Across the Universe," by "The Beatles." Most important, the Wall of Sound improved radio.

Tiny transistor AM radios, some carried in a shirt pocket, had poor-quality, one- or two-inch speakers. The sound from these radios was tinny or worse. The Wall of Sound gave a faux quality to music heard on two-inch speakers.

Radio stations, such as KHJ-AM, in Los Angeles, took a cue from Spector, using more bass and a little reverb to improve its sound. Programmers, such as John Rook, at WLS-AM, in Chicago, made the Wall of Sound their own; when listeners tuned a John Rook station, it grabbed them and they paid attention.

In 1964, Tom Wolfe, vanguard of the new journalism, wrote about Spector. Wolfe suggested Spector, enormously wealthy, was the first tycoon of teen. He was also the king of American pop music.

The king soon lost his crown. The British Invasion, especially "The Beatles," overwhelmed the all-girl groups, even the "Beach Boys." USA acts disappeared from the charts, replaced by acts from the UK.

Spector hung on, applying the Wall of Sound to an effete song, "You've Lost that Lovin' Feeling," by the "Righteous Brothers." Yet, "Lovin' Feeling" was the best example of what the Wall of Sound could achieve. A huge hit in 1965, the record has aired on radio, continually, 24/7, since its release; not a moment passes and "Lovin' Feeling" isn't airing somewhere.

His success, with "Lovin' Feeling," led to signing Ike and Tina Turner to Phillies, in 1966. He produced their "River Deep, Mountain High" album. Spector thought the album his best work, but it bombed, reaching only number 88 on the "Billboard Magazine Top 200" chart. An eponymously titled single, reached number three in the UK.

After "Lovin' Feeling" and "Mountain High," the success and influence of Spector waned. A deal, with A&M records, led to a flop, "You Came, You Saw, You Conquered," by the "Ronettes," and a small success, "Black Pearl," by "Sonny Charles and Checkmates Ltd." Spector was no longer the maker of hit records; his career wobbled and he pulled back from public life, growing more reclusive.

Spector had a small role in the 1969 cult movie, "Easy Rider." In 1971, Al Klein, who managed "The Beatles," hired Spector to produce "Instant Karma" for John Lennon; it was a hit. George Harrison and Lennon convinced Spector to rescue a discarded album by "The Beatles."

Spector redid the musical arrangements of each song, on the album. He applied the Wall of Sound and overdubbed tracks, such as "The Long and Winding Road." Paul McCartney fumed, claiming Spector worked behind his back and without his consent.

The album was "Let It Be." It was a massive hit. Three number one singles: "Get Back," "The Long and Winding Road" and "Let It Be" came from the album. McCartney was silent, content to take his royalties and bolt.

For Harrison, Spector produced a number one album, "All Things Must Pass." A number one single, "My Sweet Lord," came from that album. Spector, with Harrison, produced the triple platinum album, "The Concert for Bangladesh."

For Lennon, Spector produced what is likely the most significant album for baby boomers, "Imagine." He also produced, "Happy Xmas (War is Over)," for Lennon. In 1973, while recording "Rock 'n' Roll," with Lennon, Spector reportedly had a meltdown.

Spector allegedly pulled a gun. He took a shot or two at the ceiling. Then he vanished from the studio, carrying the original tapes. The tapes eventually got back to Lennon; he finished "Rock 'n' Roll" on his own.

Spector retreated from public life. A few failed deals, such as Warner-Spector Records, came and went. He had a few minor hits, such as "End of the Century," by the "Ramones." He received the usual past-your-prime awards.

His career in shambles and mostly over, but his wealth intact, Spector drifted into actions that are ever more unusual. Before takeoff, of a commercial flight, Spector claimed he had a vision of the plane crashing. The plane returned to gate to allow Spector and his entourage to get off.

Rumours swirled about his bizarre treatment of women. Many such rumours involved the use of firearms. None thought rumour might turn to fact, as in the death of Lana Clarkson, on Monday 3 February 2003.

Spector met Clarkson (above), an actor, at the House of Blues, in West Hollywood, California. She was a part-time host at the restaurant. After work, Clarkson accompanied Spector home.

The limousine driver, Adriano de Souza, took Clarkson and Spector to his mansion, in Alhambra, and waited outside. An hour or so later, de Souza heard a gunshot and saw Spector stumbling out the back door of the mansion. Supposedly, Spector told de Souza that he thought he killed someone.

Police found Clarkson slumped in a chair in the foyer of the mansion. A blue-steel .38-calibre revolver, with a two-inch barrel, was on the floor, near her body. Spector, at first, refused to allow police to examine his hands. There was a minor scrum. Then Spector claimed accidentally shot Clarkson.

In documents released before his first trail for the murder of Clarkson, Spector first says she shot herself, showing police how she did it. Then he tells police he didn't mean to shoot her. Finally, he claimed it was an accident.

Later, Spector claimed Clarkson committed suicide. She was, he said, at different times, distressed about breaking up with a boyfriend, poor career prospects and her life. He also claimed she asked to kiss the gun.

On 13 April 2009, after deliberating for 30 hours, the jury, in his second trail, found Spector guilty of the second-degree murder of Lana Clarkson. He received the maximum sentence, 19 years to life. Spector will be 88 years old before he is eligible for parole.

Spector filed a 148-page appeal on 14 March 2010. He claims judicial misconduct by the judge and the prosecutor. The judge allowed testimony from five women claiming Spector threatened them with a gun. Use of the word, pattern, by the prosecution, forty times during closing arguments supposedly exerted a snowballing harmful affect on the jury.

For Phil Spector, it's a sad conclusion to a spectacular career. His star shone too brightly, too quickly. It faded, with much pain, too slowly and over too many years or so it seems.

Six months after graduating high school, he had written, produced and performed on the top selling record of 1958. He developed important contacts, learned well and acted on opportunities. Between 1961 and 1965, he produced twenty hit records.

The Wall of Sound set a new, sky-high standard for pop music; its roots lie with Thomas Tallis and sixteenth century innovations in music. Spector produced hit records for George Harrison and John Lennon. He salvaged the last album by "The Beatles."

After a frustrating day recording a John Lennon album, Spector ostensibly threatened everyone in the studio, with a small calibre gun. He fired a shot or two into the studio ceiling. Except for a few sputters and spats, his career ended, in that studio, at that moment.

Still, in a recent BBC documentary, "The Agony and the Ecstasy of Phil Spector," he's cocksure of his superiority. He likens himself to Leonardo da Vinci. Spector is reclusive, fanatical about privacy and easily enraged; he has a bizarre, obsessive dislike of singer Tony Bennett.

The BBC film opens, interestingly, with a song written by Carole King and Gerry Goffin. The song was a hit, of sorts, produced by Spector, for the "Crystals." It's called, "He Hit Me (and it felt like a kiss).

Spector spent his life in the arena of public opinion. He won the hearts of a generation. This is why he was sure no jury could find him guilty in the death of Lana Clarkson.

The Spector legacy likely depends on long-term attention to the likes of Brian Wilson and Bruce Springsteen. More attention these and few other acts receive, over time, the more likely Spector raises minor interest. Of the two, Wilson and Springsteen, Wilson is mostly to be remember, with Sprector on his back.

Wilson, once a "Beach Boy" and now a shadowy wreck of promise squandered, used much the same method, as did Spector. Yet, Wilson produced a nuanced, intricate and refined sound that, musically, is much more complex than Spector; "Be My Baby" is not "Good Vibrations." New acts are most likely to take a page from Springsteen than know of Spector.

Almost 200 years after his death, Antonio Salieri, a minor composer, gets much attention. A competitor of Mozart, Salieri is a main character in the play and movie, "Amadeus." There's much scholarly interest in his work and his operas perform regularly.

Salieri is similar to Spector. There's no reason to believe, that 200 years after his death, Spector won't have at least the relevance Salieri has today; Salieri had Mozart, Spector has Wilson. Lana Clarkson, who might yet have been, won't have anything.

The influence of Spector goes beyond music, to the ethnic, gender and personal. Blacks always had a significant role in American popular culture, especially music. Ragtime, Jazz, R&B, Blues, Rock and Roll, Rap and Hip Hop are unique styles of music, distinctly American and created by Blacks. Spector solidly placed Blacks in the mainstream of pop music, on top of the charts.

More important, perhaps, Spector brought Black women, "all girl groups," into the top of pop. The "Crystals" and the "Blossoms" not only charted, each had number one hits and sold millions of records. Although these groups were pop, they infiltrated the male-dominated ranks of rock, with women-relevant lyrics.

Music provides the soundtrack of our lives. Lyrics console, inspire and elate us. His clever Wall of Sound, with inherent drama and Wagnerian climaxes, ramped up the quality of the music and lyrics, thus increasing the importance of life moments we attach to the songs Spector produced.

His fame withered, but not his wealth. Spector continued to play with guns. It was a matter of time until someone died.

The death of Lana Clarkson overshadows the successes of Phil Spector. She had a right to chase a career as an actor. She had a right to take as flattering, the attention of a pop culture icon. She had a right to go home with him. These are the quotidian decisions each of us has a right to make and not die for making.

Spector is complicit in the death of Lana Clarkson. He has a right to fiddle with a loaded gun, on his own. He has no right to use his fame and fortune to compel anyone to join his play. Allowing or urging Clarkson to fiddle with a loaded gun is reckless neglect, making Spector morally liable for her death.

Sadly, at best, Lana Clarkson might comprise a footnote, in an essay about Spector or the Rock Era; sometime in the future. Seven generations from now, 200 years, when everyone who knew or knew-of Clarkson is gone, at least some interest in Spector is sure to linger. His influence on Brian Wilson and Bruce Springsteen, among others, ensures continuing interest in him.

Jennifer Flaten lives where the local delicacy is fried cheese, Wisconsin. She writes about family life, its amusing or not so amusing moments. "At least it's not another article on global warming," she says. Jennifer bakes a mean banana bread and admits an unusual attraction to balloon animals and cup cakes. Busy preparing for the zombie apocalypse, she stills finds time to write "As I See It," her witty, too often true column. "My urge to write," says Jennifer, "is driven by my love of cupcakes, with sprinkles on top. Who wouldn't write for cupcakes, with sprinkles," she wonders.

- Warehouse Shopping

- Deep Fried Space

- Santa Claus Comes to Town

- It's a Wrap

- Lightbulbs

- Campaign Stop

- Patsy Cline

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- 67 Days

- Net Negative

- Slogans to Attract Tourists

- Sjef Frenken

- Face-to-Face with Far Folk

- Universe Nutshell

- Habits

- Jennifer Flaten

- Mysophobia

- Branded for Life

- Puppy in Charge

- M Alan Roberts

- Total Devistation

- Compassion Cracks

- A Drunk Loser

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Foggy Radio

- Grilling

- Another Graduation

- Bob Stark

- The BumbleBee

- Report Card for JT

- Jesse Jackson

- Streeter Click

- WBZ, 10 January 1973

- What is Journalism

- Stand-up Comic

- JR Hafer

- Alison Steele

- Why and Wherefore

- Larger Numbers

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- Watch Our Six

- Sadly Predictable

- The Place on the Wall

- M Adam Roberts

- Watch Your Mouth

- Blind Faith

- The Nite Busker: 2

- Ricardo Teixeira

- Monkey Business

- The Future

- There is a Light