Janis Joplin

Jennifer Flaten

All of Her Heart and More

"You could say that being yelled at by Janis Joplin was one of the great honors of my life," says Lindsay Buckingham, of "Fleetwood Mac."

It's the late 1960s. You're standing in front of a stage, shrouded in darkness. A small, lone woman stands in the spotlighted part of the stage.

She begins to sing. Her powerful voice, in turn a growl, a wail, a whisper, overwhelms you. The hairs on the back of your neck stand to attention.

You are watching Janis Joplin. "[She] had a voice that thrilled," says Myra Friedman, "with its [unusual] range and strength and awesome wails. To see her was to fall into a maelstrom of feeling that words can barely suggest."

In the documentary film, of the Monterey Pop Festival, says Lillian Roxon, "Cameras play over those rugged features of [Joplin] as if she [was] an incredible beauty and, in her very own way, she is. Men's eyes go glassy as they think about her.

"No one has gotten as excited about anyone in years," says Roxon, "as people did about Janis Joplin. She was a whole new experience for everyone." The effect of Janis Joplin withers in words, but soared with first-hand experience, now impossible.

How did an incredibly bluesy, soulful voice, an emotional abyss, emerge in a small child from the oil-refinery town, of Port Arthur, Texas? About as white-bread as possible, Joplin graduated Thomas Jefferson High School and her family regularly attended Christ Church. She and siblings, Michael and Laura, were preparing for traditional, conservative lives or so it seemed.

Joplin was a misfit, unpopular and thought weird by most. After the birth of Michael, she withdrew to paint, write poetry and play guitar. The Beat writers, of the 1950s, especially Jack Kerouac, fueled her imagination and productivity, for good and bad.

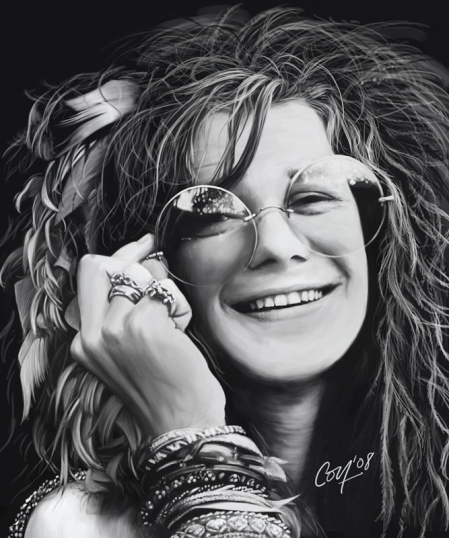

She left life for immortality, at age 27. Almost forty years after her death, she signifies rightful rebellion and freedom. A poster, bearing her iconic image (left, below) hangs promiently in a Beijing record store.

Born Janis Lyn Joplin, in St. Mary's Hospital, on 13 January 1943, she was Wednesday's Child, with a life of woe. Mother Dorothy East was the registrar of a local business college. Father Seth, an engineer, worked for Texaco.

In 1943, most young men were fighting the war in Europe or Asia. Women took their jobs, for duration of the war. When the men returned, women wanted to continue working, but confronted a repressive value emphasis and its core message: stay-at-home, have babies and know your place.

At the time, little girls could dream of nothing more than growing up to be a wife and mother. Few dreamed of fronting a psychedelic rock band, being a member of the infamous "27" or permanent fame as a singer. Joplin dared to dream.

Janis was first-born, Michael and Laura followed. As a first child, for eight years, she got much attention and developed an urge for superiority. She needed to sense she was right and in control, as does any only child in an adult world.

Born in 1951, Michael surely made Janis feel ignored or unloved by her parents; many first-borns do. When conformity, often a first response to any new stress, didn't work, Janis tried rebellion, which worked. Her parents misinterpreted her response.

As a child, Janis craved attention, said mother Dorothy. "Without extra attention, Janis was unhappy and unsatisfied. The normal rapport wasn't enough for her." Janis, claims Lucy O'Brien, was creative, which overwhelmed her parents.

First-borns, facing competition from a new sibling, often develop a special ability, such as music, to win the attention of their parents. They may present as responsible, practicing piano scales or doing homework, without nagging. This pleases parents.

Some first-borns grow gradually more discouraged. They may withdraw, perhaps into a special skill, such as painting or poetry. The special skill is under their control, they can practice when they wish; experiment and so forth, without parental consent.

Joplin, it seems, did both. She developed creative skills, which distanced her from the family, legitimately allowing much time away from them. In that distance, she developed a worldly awareness not shared by her parents and a chip on her shoulder.

It was natural for Joplin, creative and craving attention, to become a performer. She was an extrovert, that is, someone needing an above average amount of stimulation. Thus, her thirst for expression and attention were needs, not wants.

Only thousands of adoring fans, demanding her talent and screaming thanks, satisfied Joplin. A first-born child, she spent a lifetime chasing the parental attention lost on the birth of a second child. Joplin was not alone, in this sense; many entertainers talk of similar needs.

Joplin turned twenty at a time of vast social change, which she embraced. Others in Port Arthur weren't so quick to accept change, but Joplin quickly befriended outcasts and misfits. The fact Joplin easily mingled among Blacks made her stand out, in that small Texas town, and not in an acceptable way.

Her eclectic mix of friends exposed Janis to various music, but the blues called to her, most. She listened to Bessie Smith and Leadbelly, religiously. Listening to the blues, its mix of skill, conformity and rebellion, she saw music, the blues, as her destiny.

It didn't matter that she was a young, white, middle-class woman. She felt the blues in her soul and repelled at the repressive demands on women, common in the 1950s. "Man," Joplin said, "you and any housewife have all sorts of pain and joy. You'd have soul if you'd give into to it."

To learn to sing, Joplin joined a local choir. She sang relentlessly and searched for inspiration. Intelligent and reflective, Joplin sought out like-minded friends and discovered new influences, such as Odetta and Big Mama Thornton.

Trained for opera, Odetta Holmes, "Voice of the Civil Rights Movement," sang in a way none could ignore. She carried the idea of civil rights to many who might not have noticed. Odetta led the American folk music renaissance, influencing Joan Baez and Mavis Staples as well as Joplin.

Willie Mae "Big Mama" Thornton, an R&B singer and songwriter, recorded "Hound Dog," in 1952. Her version, written and produced by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, was an R&B hit that sold two million copies, at a time Black singers sold few records to the White audience. In 1955, a cover version, of "Hound Dog," was a syrupy pop hit for Elvis Presley.

Lieber and Stoller, said Thornton, "were a couple of kids. They had this song, written on a paper bag. I started to sing the words and join in some of my own. All that talkin' and hollerin,' that's my own." Thornton felt she was cheated on "Hound Dog." She said "I got one check for $500 and I never seen another."

Trained in a Baptist church choir, Thornton moved to Houston, Texas, in 1948, to further her career. As her career faded, in the early 1950s, Thornton moved to San Francisco. That was about the time Joplin did. Thornton wrote twenty or more R&B hits, including "Ball and Chain," which Joplin recorded, with "Big Brother and the Holding Company."

When Joplin talked about what influenced her, the Blues and "Big Mama" Thornton topped the list. In 1984, Thornton was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame.

Joplin didn't recall high school as a good time. She learned to sing, write poetry and paint, but an emerging concern for social issues and many Black friends distanced her from the mainstream. Problems of puberty didn't help, as her adolescent acne left deep, permanent scars.

The scaring brought unwanted attention. Often bullied and taunted about the scaring, her high school years were miserable. She became a lonely young woman, with a chip on her shoulder, who couldn't wait for high school to end.

After high school, Joplin tried Lamar State College of Technology. The appeal of the school was mostly its location, Beaumont, Texas. She wanted to jettison Port Arthur and its inbred negativity.

Joplin wasn't alone is her dislike of Port Arthur, "a foot fungus," along the Texas-Louisiana state line. "Business Week" magazine, a sober supporter of all that makes money, called the oil-refinery town, of Port Arthur, "one of the ten ugliest towns on the planet." To Joplin, "it was a smelly, stultifying, mosquito-ridden swamp," says Alice Echols.

A small school, Lamar State didn't fulfil her creative needs. Joplin transferred to the University of Texas, in Austin. Here she found her voice.

At UT Austin, she got much attention for campus activism and performing in Austin clubs and coffeehouses. The "Threadgill Bar" was a regular booking for Joplin. At the Threadgill, she was part of a trio, "The Waller Creek Boys," with Lannie Wiggins and Powell St. John.

Joplin adopted a style suggestive of Bessie Smith, Odetta and Thornton as well as Beat Generation writers and poets, such as Jack Kerouac and Alan Ginsberg. Powell St. John was a self-styled Beat writer. The "Daily Texan," the UT Austin student newspaper, headlined a 1962 profile of Joplin, "She Dares to be Different."

She thrived. She plied and honed her image of a blues woman and Beat writer. In December 1962, she recorded her first song, "What Good Can Drinkin' Do," at the home of a friend.

Three months later, in March 1963, Joplin left Austin for San Francisco. She settled in North Beach. Then, as every Beat Generation or Hippie want-to-be, she moved to "The Haight," the area around the corner of Haight and Ashbury streets.

In "The Haight," Joplin found kindred souls, with much talent. Many Beat Generation writers migrated to "The Haight," from New York City, in the early 1960s. St. John turned up, too. Joplin recorded several songs, crudely, with Jorma Kaukonen, the future lead guitar of "Jefferson Airplane," and his wife, Margareta Kaukonen.

Margareta Kaukonen suggested using a typewriter as a percussion instrument. Her idea likely drew on the Buddy Holly song, "Everyday," which uses a varied typewriter metre. Joplin and the Kaukonens recorded seven songs: "Typewriter Talk," "Trouble In Mind," "Kansas City Blues," "Hesitation Blues," "Nobody Knows You When You're Down and Out," "Daddy, Daddy, Daddy" and "Long Black Train Blues." After Joplin died, a bootleg version of this recording session released as "The Typewriter Tapes."

By 1963, Joplin was abusing amphetamines, such as Dexedrine. Amphetaminesare addictive, give short, intense bursts of alertness and energy; deaden appetite and lessen the need for sleep. Also known as speed, amphetamineshelp keep anyone, with a chaotic or emotive drive, going all night and day, without losing focus. Joplin also used heroin and a steady stream of Southern Comfort, a pure grain alcohol available as 100 US proof.

Eventually, her friends recognized her wild descent into substance abuse. They rallied to help, living with her, keeping her busy and distracted. Their help worked, some, but, finally, they decided to send her home to Paris, Texas, throwing a farewell party to raise the bus, hoping she might get her life together.

Back home, Joplin dove headlong into changing her life. She stopped using drugs, changed her look and embraced home and hearth. At Lamar College, she studied sociology. Her friends saved her life, for the moment.

What Joplin didn't change was her thirst for performing. She worked the Austin, Texas area, mostly as a solo, voice and a guitar. Her act lacked flash, but a reviewer, writing for the "American Statesman," liked it.

Joplin sent the review to friends in San Francisco. "Hey, I'm a star with a beehive hairdo." Surely, her friends revelled in her new, clean lifestyle and local success.

Chester "Chet" Helms read her review. A musician and promoter, Helms was California born, but grew up in Texas. He knew Joplin casually, but went to Port Arthur to talk her into returning to San Francisco. Would she front a new band, "Big Brother and the Holding Company"?

Helms, the driving force behind the "Summer of Love," in 1967, put San Francisco on the music map. Through Family Dog Productions, he produced free shows in Golden Gate Park, Fillmore Auditorium and Avalon Ballroom. His psychedelic light shows, which added much to the audience experience, became part of concerts, everywhere.

Shortly after returning to San Francisco, Joplin wrote her parents. She was there to stay, at least for now, but wanted a recipe for cookies and advice on how to remain a good daughter. Helms, by the way, arranged for her to audition for "Big Brother," she said.

"Big Brother" debuted at the Avalon in June 1966. The light show added interest, making the mediocre band a success. "Big Brother" became the top band in the Bay Area.

"Big Brother" spent August 1966 performing in and around Chicago. Bob Shad, owner of Mainstream Records, offered a recording contract. The day after signing, with Shad, "Big Brother" was in his Chicago Recording Studio, resulting in the album "Big Brother and the Holding Company."

After the recording sessions and out of money, Shad refused to advance "Big Brother" their airfare home. Undaunted, the band drove to San Francisco. Back home, but gone for a month, they had nowhere to live.

The "Grateful Dead" came to the rescue of "Big Brother," offering to share digs. Joplin lived, alone, by luck she surely thought, in a huge home in Lagunitas, California. This good fortune was her downfall.

Early in 1967, Joplin took up with Joseph Allen McDonald, a Washington, DC, native who moved west. He fronted a band, "Country Joe and the Fish," best remembered for the "Fish Cheer" or "Give Me an F," performed at Woodstock. Joplin found, she thought, domestic bliss, but didn't.

The success of "Big Brother" grew. Los Angeles was their second home, including a show at the Hollywood Bowl. Helms got "Big Brother" booked for the Monterey Pop Festival, in 1967, which was a major coup. For his efforts, Helms good news, Columbia Records signed the band, and bad news, the band signed with a new manager.

At Monterey, talent manager, Albert B. Grossman, saw Joplin. He wisely signed her to a long-term contract. Seems he reluctantly signed "Big Brother."

Not to devalue Joplin or her talent, but Grossman signed anything that moved, to a long-term contract. A former municipal employee, in Chicago, Grossman opened a club, the "Gate of Horn," in the basement of the Rice Hotel. His plan was to make money, featuring local folk singers. He did: the idea and the club hit the right note, at the right time.

According to Dylan, "[Grossman] looked like Sydney Greenstreet, from the film "The Maltese Falcon"; [he] had an enormous presence, always dressed in a conventional suit and tie, he sat at his corner table. When he talked, his voice was loud, like the booming of war drums. He didn't talk so much as growl."

Grossman worked a cynical version of the law of averages. Sign acts, in bulk, and a few, will make you money and it did. After moving to New York City, he scoured Greenwich Village, each night, looking for new talent.

He was ready to sign anyone. His coat pockets contained filled-out contracts, ready for unsuspecting talent to sign. His inside jacket pocket was reserved for singers who wrote songs. Contracts for record producers filled the right, outside pocket, of a coat, and so forth.

Trying to sign Baez, after moving to New York City, Grossman supposedly said, "Look, what do you like? Just tell me, what do you like? I can get it for you. I can get anything you want. Whom do you want? Just tell me. I'll get you anybody you want." He failed Baez, not getting her Bob Dylan back.

By the 1960s, Grossman managed, among others, "Peter, Paul and Mary," "Ian and Sylvia," John Lee Hooker, Phil Ochs, Gordon Lightfoot, Richie Havens, "The Band," Odetta, Joan Baez and Bob Dylan. He told Robert Shelton, of the New York "Times," "The American public is like Sleeping Beauty, waiting for an awakening kiss from the prince of Folk music." In 1959, he formed the Newport Folk Festival, with George Wein, Theodore Bikel, Oscar Brand and Pete Seeger, arranging for the Folk Music revival.

Grossman aimed for financial success for his clients. Thus, he ruffled many of the "one for all and all for one" new wave folkies. Among folkies, the message was the music and making money, beyond need, was heretical.

The Grossman management fee was twenty-five per cent. The norm was fifteen per cent. "Every time you talk to me," he'd say, "you're ten per cent smarter than before. I just add ten per cent on to what all the dummies charge for nothing."

When Grossman signed Joplin and "Big Brother," he insisted on no intravenous drug use. Everyone agreed. In 1969, he discovered Joplin was using heroin and took out an insurance policy on her life.

The insurer balked at paying Grossman, after Joplin died, claiming he knew of her drug abuse and she committed suicide. Grossman claimed ignorance of the full extent of her drug use, saying he had plane crashes and such in mind, when he took out the policy. In 1974, the insurer made good on the policy payout.

"Big Brother and the Holding Company, featuring Janis Joplin," their first album for Columbia, released in August 1967. Cuts included "Combination of the Two" and "Ball and Chain," recorded live. Donn Pennebaker featured "Big Brother" and Joplin prominently in his 1968 documentary, "Monterey."

Counter-culture artist, Robert Crumb, designed the cover, of the second album for Columbia, "Cheap Thrills," which included "Piece of My Heart." Originally recorded by Erma Franklin, older sister of Aretha, "Piece" was number one, on the "Billboard Top 100," for eight weeks. A tour, in support of the album, included the "Ed Sullivan Show" and Newport Folk Festival.

On 1 June 1968, Joplin told "Big Brother" she was leaving for a solo career. Grossman knew a solo act, with quality back up, made more money than did a group and with fewer hassles. Joplin formed the "Kozmic Blues Band," for backup, around Sam Andrew, of "Big Brother." She stayed on Columbia Records and gave her first solo show, in Memphis, TN, on 21 December 1968.

Joplin also tried to stay sober. It was a struggle, too much stress and too many substance abusers around her. Sobriety was brief for Joplin.

By 1965, heroin was her drug of choice. Joplin might drink two or three quarts of Comfort during one show, using heroin to calm her, afterwards. On tour, she might do four to six shows a week. Her skeletal frame, chubby as a child, confirmed the physical toll of substance abuse: Joplin was a junkie.

After a show, at Madison Square Garden, in New York City, Joplin told journalist, David Dalton, "The audience watched and listened to every note, with a 'is she gonna make it?' in their eyes." Every show, says O'Brien, she turned herself inside out, trying to be what she thought her fans expected. The pressure, said Joplin, sent her scrambling for a crutch, that is, drugs and alcohol.

Her then fiance, Seth Morgan, "was an unstable conman from a privileged [home]." In 1990, Morgan died in a "motorcycle crash, high on alcohol, cocaine and Percodan," O'Brien says, "with his [lover, riding on the back,] beating him, crying desperately for him to 'slow down'." Joplin and Morgan shared a habit and little else.

Efforts to keep her sober, to record her first solo album, "Kozmic Blues," failed. By 1969, her heroin habit cost a $200-a-day. When she started to record or walked on-stage, writes Alice Echols, a Joplin biographer, "She was three sheets to the wind."

At the end of 1968, the "Full Tilt Boogie Band" replaced the "Kozmic Blues Band" behind Joplin. Comprised of young, talented Canadian musicians, John Till, Richard Bell, Brad Campbell, Clark Pierson and Ken Pearson, "Full Tilt" infused Joplin with new energy. The relentless touring continued.

About the same time, Joplin added a "fashion sense" to compliment her music. "She lopes about," writes Roxon, "dressed like a dockside tart, funny little feathered hats, ankle bracelets, sleazy satins. Her hooker clothes, she calls them, with a hooker laugh." Styles change little: in 2009, "Lady GaGa" told "Ellen" she buys many of her most popular costumes at a store specializing in clothes for strippers.

Joplin appeared on the "Dick Cavett Show" several times. Cavett, who hosted a series of talk shows that struggled to find an audience, often interviewed celebrities other shows avoided. Joplin beguiled him.

Offering to light her cigarette, on one show, Cavett said, "Let me light my fire," alluding to a hit record by "The Doors." Joplin replied, "He's about my favourite singer." her reference was to Jim Morrison, of "The Doors," on whom she had a huge crush.

Cavett got Joplin to reveal a different side. She opened to him. "Why are there so few rock super star women," Cavett asked. His question was on mark, rock lyrics and stage-style, such as smashing instruments and setting fires, left women out.

Joplin said, "I wonder about [the lack of women in rock, too]. Maybe it isn't feminine to get on the bottom side of a melody, as I do. Too many women [singers] flitter around on top of the music."

What isn't feminine? A woman, O'Brien says, "Driven, expansive, out of control" in the world of rock, dominated by men, isn't feminine. It was all right for men to sing rambling, mostly misogynistic lyrics and fall into substance abuse, but not women.

Women should know their place. The idea of place, a relic of the repressive 1950s, languished in rock. Libertine music, rock, which proclaimed rights and freedom for all, was gender regressive.

What's "getting to the bottom," of the music? Again, O'Brien says it well: "When Joplin stood on stage and screamed out "Piece of My Heart," there was a sense of megalithic rock reinterpreted," rescued through the perspective of a woman. This wasn't feminine, either, for the time.

"It's the same for everything," said Joplin to Cavett. "Getting into the rhythm, to the bottom of anything, not skirting it is important. Just let everything out, then there's nothing but pleasure." For as much attitude, as they can dish, she was saying, most women can't let loose and have a good time. She, of course, was alluding to her performance style.

Cavett asked what she thought about when she sang. Joplin said, "I don't think about anything, at least I try not to think. I try to feel the music."

After confiding to Cavett that she'd attend a high school reunion in Port Arthur, he asked, "Were you popular in high school?" She admitted her schoolmates "laughed me out of class, out of town and out of the state; so I'm going home." She did.

The reunion at Thomas Jefferson High School didn't go well. A classmate, of Joplin, told Chet Flippo, of "Rolling Stone," she wore enough jewellery for a Babylonian whore. Asked if she entertained while a student, at the school, Joplin said, "Only when I walked down the aisles."

Harvard Stadium, in Boston, Massachusetts, on Wednesday, 12 August 1970 was her last live show. Atypically, the "Harvard Crimson" gave the show a solid review. The review was doubly gratifying as the show was full of woe. Someone stole the band equipment, the night before. The show went ahead, using rag-tag instruments and a second-rate sound system.

During her final weeks, Joplin recorded songs for "Pearl," the album epinomous for the nickname her closest friends gave her. After a long day recording, she ambled into the parking lot, with members of her band. Joplin said, "Who's got the biggest balls here?" After a brief pause, she said, "I do."

The "Full Tilt Boogie Band" was her band. She hired the musicians. She paid them. She could fire them. Joplin was a superstar woman, in rock, and in but not under control.

On Sunday 4 October 1970, Joplin didn't arrive to record the lyrics for "Buried Alive in the Blues." Unable to contact her, by phone, road manager, John Cooke, drove to the Landmark Motel Hotel, now the Highland Gardens Hotel, where she was staying. He saw her Porsche in the parking lot.

Cooke found Joplin on the floor, of her hotel room. Officially, she was the victim of a heroin overdose, from her secret stash. Weary, from a long day of recording, she mistakenly injected a lethal dose of heroin or so goes the story.

Paul Rothchild, producer of "Pearl," cobbled material for an album. He used the first take of "Mercedes Benz" and an "a cappella" version of the song. "Me and Bobby McGee," written by her then lover, Kris Kristofferson, became the biggest hit of her career. Rothchild left "Buried Alive in the Blues" as an instrumental, a memorial: the rider-less horse, the vocal-less song. In 2009, the Grammy Hall of Fame inducted "Pearl" into its recording category.

A California girl, in the end, her ashes spread along the Pacific Coast and at Stinson Beach. Sour home, Port Arthur, Texas, lost Joplin forever. Freedom isn't just another word for nothing left to lose, but for self-esteem, with everything to gain.

Joplin had a brief career: four years and four albums, one posthumous. Her after-life career soars, her influence spreading as wild grass. A poster of her hangs, prominently, in a Beijing record store.

She found the attention she needed. A few women, says Susan Douglas, broke through, to rock stardom, in the late l960s, most notably Janis Joplin. "She was the first White woman," says O'Brien, "to negotiate the murky depths of [rock; she] made up the rules and suffered for it."

Lifestyle fuelled the attention, talent made her true. Richard Goldstein, writing in "Vogue, called Joplin "the most staggering woman in rock. She slinks like tar, scowls like war, clutching the knees of a final stanza, begging it not to leave. Joplin can sing the chic off any listener."

Joplin had a multiple reaction to the birth of her brother, Michael. She rebelled, developed highly creative skills and grew dispirited; most first-borns have a single response. This early and atypical response may have sent her down a fatal path to success.

It's often hard to imagine the extent of her success. At a 11 December 2009 concert, in Perth, Australia, Stephanie Nicks, of "Fleetwood Mac," told the audience about opening for Joplin. "There were 35,000 people at that show," she said, "the constant guitar playing by Lindsay drove the gated community crazy; they wanted Joplin, not me signing 'Gypsy' and him playing on."

The first woman superstar in the male world, of rock, was cause for much suffering. Joplin won using new rules, she made up; she was widely criticized, inside and outside the rock world. She made a mistake, though, which O'Brien says made her suffering worse.

Joplin tried to live up to her ideas about what the audience needed and wanted. The goal was impossible to achieve. This was a huge mistake; an artist creates to satisfy his or her own urges, first, if others like their work, so much the better.

Susan Douglas saw Joplin perform, in the late 1960s. "[She] drank about three quarts of bourbon, on stage, cursed the security guards and sang her guts out." This was good for the image, but lethal for the person.

Joplin paid for her image. She let in the wrong lovers, such as Seth Morgan, keeping the right ones out. Once a chubby child, at the end, she was a skeleton, the victim of substance abuse.

Isolated by stardom and substance abuse, the call of the void had an appeal. Joplin may have feared fleeting success. Maybe she sensed only one choice would present, that is, inevitable failure.

Failure was an existence, not a life, in Paris, Texas: her hair in a bun, two kids, a mortgage and a cheating spouse. "What's happening never happens there," Joplin said about her home town; it was the great nowhere.

Joplin would make the choices. Returning to Paris was not a choice, for her. Better a heroin daze, dead or something like it.

Joplin sought love and attention through rock. All she thought she found was shame and overlooked the love returned. For the time, hers was a shameful choice for women.

Shame is mostly self-evaluation, often rooted more in doubt than fact or act. The price for rebels is self-doubt, which deflates their self-image, self-esteem and sense of worth; this is why many creative women and men self-destruct. Rebels, who blaze trails, usually pay a hefty price, which followers don't because someone went before them.

Love is positive, directed at the other. Joplin went all-out to show love for her audience. Although negative, for her, the effort was positive for others.

Joplin too readily accepted the labels applied to her by others. The labels were less than loving, but eased by her crutch, Southern Comfort and heroin. Show after show, Joplin did what she must, the devil be damned.

Joplin surely knew her acts confirmed false labels. Mostly three sheets to the wind, when walking on stage, thrusting her hand down her unzipped pants, drinking three quarts of Comfort during a show and likely calming by heroin, afterwards. She continued because she believed others expected it.

For the labelled, labels grow into a lifestyle. Shame, though painful, in many ways, is an accepted daily state; this is what I am. The two sides, love and shame, rarely mesh, always in conflict.

Shame leads to mistaken love, the wrong lovers or loss of love. In a large sense, song lyrics, regardless of genre, confirm women, especially, must have love or live in shame. The leitmotif, of these lyrics, is conformity to get and keep love; non-conformity is shameful.

The result is confusion. If I am my own woman, can I be a good person, worthy of love? The conventional answer is no. Must I suffer humiliation from my unfeminine acts, such as getting on the bottom of the music or strongly sensing the emotive power of music? The conventional answer is yes. Joplin was not conventional.

Home and work do battle in the confusion. At home, I find love if I hold fast to brutal, dated demands for women. At work, labelers shame me for creative expression, innovation and fame.

The confusion, which seems relentless, can lead to extreme acts, such as suicide. The victim senses a need to avoid loss of love or escape shame, but can't act to these ends; the creative urge overwhelms. The suicide decision may be conscious or subconscious, set in motion by a momentary misjudgment.

Losing love confirms one is an unworthy person. Shame is painful, whether the pain shows or not. This equation is toxic, at best, deadly, at worst.

It seems the Joplin self-image precluded personal love, which left her life devoid of much meaning. That image rooted firmly in her childhood. Her creative urge and fame lead to the label, rebel woman, suggesting whore. Shame, mostly sensed, followed.

Joplin redefined the woman singer, much as did Aretha Franklin, but she was White. "[White women] are not supposed to sing that way," said Lillian Roxon, "all hoarse and insistent and foot stamping. They're supposed to sound as if they're shrieking for delivery from some terrible, urgent, but not entirely unpleasant, physical pain."

It was all right for a Black woman, such as Tina Turner, to give everything, drive hard and maintain on-stage control. The motivation, of a White woman, from Paris, Texas, to the same goals, was suspect and shameful. Janis suffered for leading the way.

The two faces of Janis Joplin seem love and shame. The self-styled unworthy person needed much attention, as do all first-borns. Many men and women face confusion rooted in a lack of love and sensed shame; most chose to hide away.

Joplin took a permanent vacation from her demons, although she found the attention and creative outlet she yearned. Years of substance abuse may have weakened her will. A tiring day, recording "Pearl," may have distracted her, at the last moment.

Whatever the cause, Joplin joined Robert Johnson, Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Kurt Cobin and Ron "Pigpen" McKernan, among others, music superstars who died at age 27. The company is good, but 27 is a scary age for rockers and those who deal in rock. Each star died as their careers started to peak, but gained more fame, in death, than in life.

Joplin, as the others, left too soon. Still growing, maybe unaware the angst and fears of a young adult subside, with time. Still, fame is a bizarre drug and its effects bewildering.

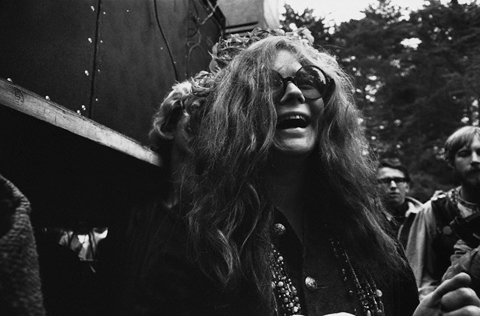

Joplin in Golden Gate Park, in San Francisco, summer 1968.

Epilogue

"[Joplin] had a huge appetite for life," says Sam Houston Andrew, of "Kosmic Blues Band" and "Big Brother." "Part of her life was drinking and taking drugs. It didn't have to be, but it was. Joplin had a big appetite for such abuses. That's something that's wrong.

"As far as dying, I lucked out and that's the truth. It's just luck. It could've been the other way around.

"Insecurity was one thing that was wrong with Joplin, but don't let it sidetracked us. She was a happy person. She had a good time, most of the time. She enjoyed life, too.

"Her suicide was an accident. She came so far, in her life, from this little town in Texas, where people made fun of her; suddenly everybody loves her. Anyone who thinks a lot and Joplin thought a lot, is gonna question and wonder if it's all gonna disappear, which it could, but she didn't let it."

Sources

Ellis Amburn (1992), "Pearl: the obsessions and passions of Janis Joplin," published by Time Warner.

Susan J. Douglas (1995), "Where the Girls Are: growing up with the mass media," published by Three Rivers Press.

Alice Echols (2000), "Scars of Sweet Paradise: the life and times of Janis Joplin," published by Metropolitan Books.

Myra Friedman, (1992), "Buried Alive: the biography of Janis Joplin," published by Crown.

Lucy O'Brien (1995), "She Bop: the definitive history of women in Rock, Pop and Soul," published by Penguin.

Lillian Roxon (1969), "Rock Encyclopedia: biographies, discographies, commentary and analysis," published by Grosset and Dunlap.

Jennifer Flaten lives where the local delicacy is fried cheese, Wisconsin. She writes about family life, its amusing or not so amusing moments. "At least it's not another article on global warming," she says. Jennifer bakes a mean banana bread and admits an unusual attraction to balloon animals and cup cakes. Busy preparing for the zombie apocalypse, she stills finds time to write "As I See It," her witty, too often true column. "My urge to write," says Jennifer, "is driven by my love of cupcakes, with sprinkles on top. Who wouldn't write for cupcakes, with sprinkles," she wonders.

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- The Great Butter Heist

- Valentine's Day Gift

- Out of the Rubble

- Sjef Frenken

- Fat Chance

- A Gay Blade

- Apocalypso 782

- Jennifer Flaten

- Book 'em

- Linen

- April Fools Day

- M Alan Roberts

- Sea Stories 1

- Fit to Survive

- Wild Horses

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Power

- Shaken, Not Stirred

- Big or Small

- Bob Stark

- Hear! Hear!

- Stanley Cup 2014

- Pinocchio's Son

- Streeter Click

- Police Drama of 1950s

- Shane McGown Live, Bio

- Mission

- JR Hafer

- Habit-forming

- Scott Muni

- Life as a Classroom

Recommended

- Jane Doe

- Hooters as Work

- A New Day

- Top Gear

- M Adam Roberts

- Thanks a Million

- The Secret

- Son of a Gun

- Ricardo Teixeira

- Harmony

- Monkey Business

- There is a Light