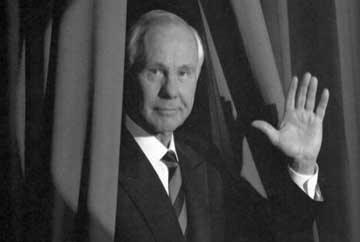

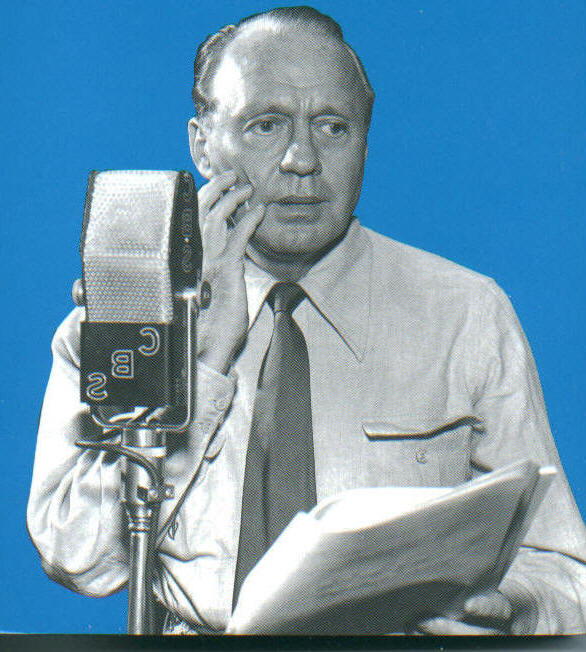

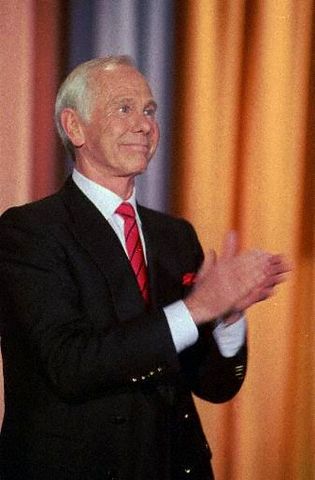

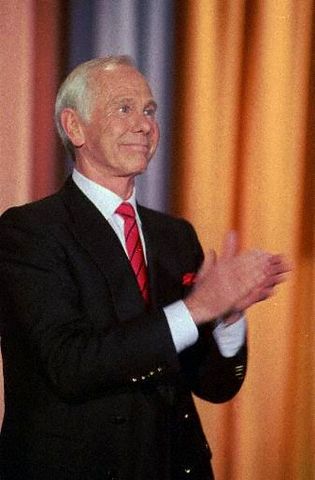

Johnny Carson

dr george pollard

Johnny Carson retired more than 22 years ago, 22 May 1992. On Friday, he was there; 50 million saw him. On Monday, there was a void that remains.

The "Tonight Show," many say, lost vigor and much relevance when Carson left. His legacy is awesome. Over 29 years, 7 months, 21 days and 3100 hundred shows, he performed 4,500 stand-up bits and 3,500 skits that made 20 million viewers laugh and many go "aha." He interviewed 25,000 guests, making the good look better and letting the bad do in themselves. His body of work is without equal, in breadth, depth and effect. Only Bob Barker, formerly host of "The Price is Right," has more time hosting a network television show, in the USA.

Open and honest, Carson joked about success, never fully at ease with it. Classy and civil, a sidelong glance made his derisive points sting, silently. His satire, cutting, hidden in bombed jokes, raised awareness. A Carson monologue made you think, and grateful.

The funniest moment, on the "Tonight Show, starring Johnny Carson," was a marmoset urinating on his head (above). The saddest moment was actor, Jimmy Stewart, reading his poem, "My Dog Beau"; Carson cried, quietly. The best performance was Bette Midler, on the second last show.

Carson gave much and paid heavily. On the final show, he apologized to sons, Kit and Cory, for "not being there enough," saying he loved them. He expressed deep regret about the death of son, Richard. This side of Carson caught some, mostly casual or unfeeling viewers, off-guard. A fourth marriage was lasting and happy.

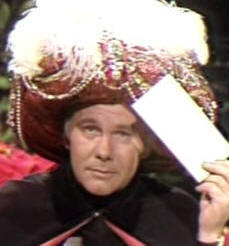

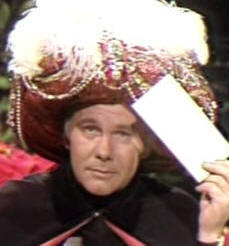

Carson, above as "Carnac the Magnificent," is the most pervasive humorist. Yet, he flies below the radar these days. Do a search. You'll find more than a million relevant pages. Most of these pages plagiarize a few authentic comment pages to help brazenly flog Carson product. Art Fern was never so callous. "Comedy is serious," says Howard Lapides. "A good joke is hard to find, harder to deliver, convincingly. Carson made it look easy, and he let us share his fun."

Legacy and style are smoke and mirrors. Carson's a classic enigma. Push the facade aside to find untold intricacies. Is it any wonder unique comments about Carson are rare? Only a nuanced mind can make deep insight and hard work seem easy, as did Carson. Carson's not a trifling jokester, but genuine, satirical and original, one of a very few.

President Honours Cornhusker

On 11 December 1992, Johnny Carson received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The award was for hard work. The Medal confirmed the importance of his work and the effect he had on you and me.

The Medal is for "an especially meritorious contribution to the security or national interests of the United States, world peace, cultural or other significant public or private endeavors." The list of recipients includes Jonas Salk, I. M. Pei, Will Durant, Neil Armstrong, William F. Buckley and Earl Warren. The company's good. The neighbourhood has high standards. (Left is the official Presidential Medial of Freedom photograph, 1992.)

Months earlier, on 22 May, Carson retired from television. He'd hosted the "Tonight Show" for almost 30 years, and before that game and variety shows. For 40 years, he made millions of women and men laugh, and one television network wealthy.

Does a television host deserve a Presidential Medal of Freedom? One time only; the Medal has gone to only eight radio and television performers. Medals went to news workers, David Brinkley and Paul Harvey. For educational efforts, Fred Rogers, Julia Child, Peggy Charren and Bill Cosby received the award. Two actors, Carol Burnet and Andy Griffith, received medals. Carson's the only host to earn the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Carson, said then-President George H. Bush, "with decency and style ... made America laugh and think." There's the rub. A host can joke or conduct interviews, and make the moment better. Anybody who makes us think propels us into a better future. If done with decency and style, the Carson style, we're all better off.

Being There

It's not easy to convey the importance of Johnny Carson. Every night, 20 million women and men went to bed and watched Carson. The worst gags from his monologues got the widest circulation. Non-viewers heard his jokes from viewers. Many viewers were water cooler comics. This went on for 30 years.

Carson was a unifying force. "I can remember," says Steve Parker, "The Car Nut," sitting on the steps of our basement in our home in Rockville Centre, NY, [a small city on Long Island], to sneak views of the family television, as my parents watched Steve Allen and Jack Parr, and then Johnny. [He] became a serious touchstone in our family," says Parker (left). "No matter what else was going on, in the family or the world, watching Johnny each evening was a pleasure we all greatly enjoyed, mom, dad and me."

"Carson has always been my favorite television personality, bar none," says Parker." My mom and I saw him 'in concert' at the Anaheim Convention Center, with the Doc Severinsen Band - best band ever on television.

"Johnny was a bit aloof, I think ... we all knew he was very wealthy, but he made jokes about it, which served to humanize him to us all.

"It was a sad day ... when Carson retired, no matter how planned and contrived the last few shows might have been. It is, after all, "show business," .... So what if they planned the final song by Bette Midler, weeks in advance? That's good show business, and it wasn't any less sad."

To think Carson was merely pervasive is to misjudge his presence. He was an icon, a symbol, giving voice to the baby-boomers, their parents and their children. He gave us a rallying point and helped us bond.

Life

Born in Corning, Iowa, on 23 October 1925, and John William Carson grew up in Norfolk, Nebraska. The urge to perform, to make people wonder, and think, came early. At 14 years old, he worked as "The Great Carsoni," a magician (right), and as a ventriloquist. He told a biographer, Richard Cockery, that entertaining was a given in his life: he never thought of doing anything else. Other than two years in the Navy, during World Ward 2, all Carson did was entertain.

Sundays, Carson often said, were the best. It wasn't church and family events, as you might think. Jack Benny made the day special. Carson idolized Benny.

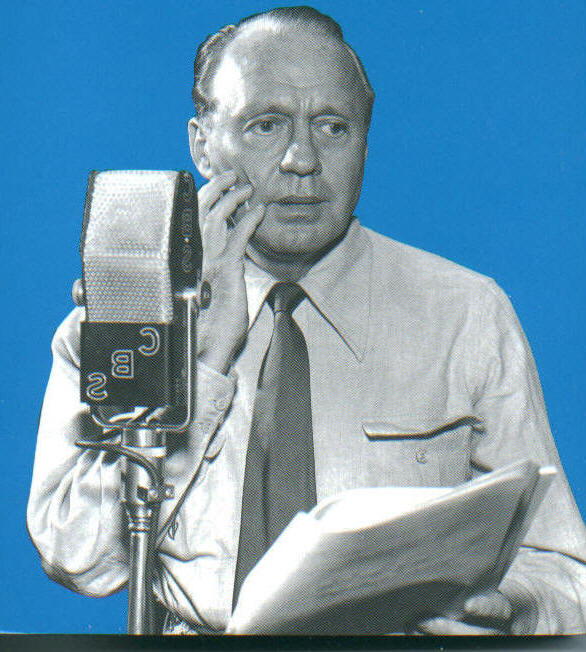

Well-written, thoroughly rehearsed and intricately performed, "The Jack Benny Show" is the prime example of a comedy show. Never bawdy, Benny (above, about 1932, the began in radio) was always more vaudeville than burlesque. He confirmed great comedy didn't come at the expense of others. The Benny ensemble teased and joked about one another. All good friends do the same, to show camaraderie.

The Benny style was never bitter, certainly not on air. There was no acidic edge, as there is often among rivals in an ensemble. Benny teased, al lot, mocking or taunting only in jest. He could take a joke, a tease, better than most. Carson was the same.

Benny was superb at the running joke, such as his stinginess. He was cocksure of winning an Oscar, even in years he didn't make a movie. The Benny character was equally sure he was the most popular fellow in Hollywood.

The Benny timing was subtle. Accosted by a mugger, who blurts, "Your money or your life," Benny says nothing. After a few seconds, the mugger, growing anxious, says, "Come on, come on; your money or your life." Undeterred, Benny waits. After more badgering by the mugger, he eventually says, "I'm thinking. I'm thinking."

"The Jack Benny Show" was for the family. It worked on many levels, making children, adolescents and adults laugh and feel good about themselves and each other. The best Benny laughs came after a moment of thought. "The Jack Benny Show" was always general, and never specific or harshly critical. Jack Benny appealed to listeners, regardless of the values they embraced, and he still does. Above,� Benny, ever the penny pincher, pondering the wisdom of his 1 January 1948 move from NBC to CBS. Apparently, CBS has reneged on its promise of a free parking spot for the Maxwell.

Benny was a mainstay of radio from September 1932. In the early days of radio, new episodes of most shows aired several times a week. At first, "The Jack Benny Show" ran Monday and Wednesday. In early 1933, the show added Sunday. Starting 4 October 1936, "The Jack Benny Show" began a 19-year run Sunday at 7 pm, on the east and west coasts; 6 pm Mountain and Central time. Carson began the "Tonight" show, Monday 1 October 1962.

After supper, maybe an early supper, the Carson family would gather around the radio to listen to "The Jack Benny Show." Johnny and his younger brother, Dick, lay on their tummies, in front of the radio, sure not to miss a sound. Sister, Catherine, might browse a magazine as she listened. Dad, Homer, also known as "Kit," might read the paper while listening. Mother, Ruth, might darn and listen.

Whatever the details, one fact is sure. The influence of Jack Benny on Carson intensified because the family listened together. The Benny style is obvious in the work of Carson, as is the tacit decorum needed to play to everybody.

Benny gets an award from Carson in the late 1960s.

Influence is strongest in the background. Benny ended his ra dio show on 22 May 1955. The final "Tonight Show, starring Johnny Carson" aired on 22 May 1992. Was this homage? Did Carson tease and taunt about retiring until the day was right: Friday, 22 May? No one is talking.

dio show on 22 May 1955. The final "Tonight Show, starring Johnny Carson" aired on 22 May 1992. Was this homage? Did Carson tease and taunt about retiring until the day was right: Friday, 22 May? No one is talking.

Navy recruit and boxer

After high school, Carson joined the US Navy for the duration of World War 2. He told a mockingly unimpressed, Mohammad Ali , he boxed in the Navy. Nine bouts and no losses, he told Ali, who yawned. "I came away without any marks," said Carson. "Me, too," said Ali, "and much more pretty."

Carson served on the USS Pennsylvania. He decoded and delivered messages. Once he hand delivered a message to James Forrestal, wartime Secretary of the Navy. Forrestal, says Carson, asked if the Navy was his career. Carson replied no, telling Forrestal his dream of being a magician and entertainer. Forrestal asked Carson what card tricks he knew. Johnny happily did a few tricks, told a few jokes and got a round of applause from the Secretary of the Navy.

After two years at Millsaps College, in Jackson, Mississippi, Carson entered the University of Nebraska. That was 1947, and he graduated in 1949; a degree in speech, with a minor in radio. He submitted his undergraduate thesis, about radio comedy, on tape. Though it's now common practice, Carson submitted the first known thesis in audio form.

On 1 October 1949, Johnny married Joanie. Joan Morrill Wolcott(1926-) was his college sweetheart. They had three sons: Chris (1950-) Richard (1953-1991) and Cory (1953-). Wolcott and Carson divorced in 1963. Richard died in a car accident, in 1991. (/p>

Career

Despite a deep interest in radio, Carson worked only briefly at WOW-AM, in Omaha, Nebraska, before moving to WOW-TV. In the late 1940s, there were many television opportunities. Stations were going to air, rapidly, at the rate of two or three a week. In 1945, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) lifted a wartime ban on new licences. By 1948, television stations were popping up everywhere.

Carson took advantage of the new medium. At one point, he hosted an early morning show called, "The Squirrel's Nest," on WOW-TV. Then he moved his family to Los Angeles.

As a writer for "The Red Skelton Show," Carson got his career moment, in 1951. Injured backstage, just before the show was to go live to air, Skelton needed a replacement. Carson was ready, and delivered his first monologue to a national audience.

KNXT-TV, in Los Angeles, gave Carson his first big city on-air job, in 1953. "Carson's Cellar") taped at the Don Lee Broadcasting Studio, at 1313 Vine Street, in Hollywood. The local show ran for a year or so, and seems an extension of "The Squirrel's Nest" idea. Above, left, Carson as school boy in a skit from "Carson's Cellar."

In 1954, Carson hosted "Earn Your Vacation," a weekly half-hour game show. There wasn't much network interest in the show. There's wasn't much interest in the show, anywhere. He also tried acting, appearing on "Playhouse 90," in a minor role.

From 1955 to 1957, "The Johnny Carson Show," a weekly half-hour variety show, ran on CBS . Mixed reviews hurt. Yet, the show ran three seasons. "The Johnny Carson Show" likely benefited most from the first-time sales of television sets. Viewing was still a new activity. Viewers were learning how to watch and make choices.

Trampolines were all the rage, in 1955. the an Hoola Hoops weasa year or two away.Above right, is a trampoline act on the first "Johnny Carson Show," on CBS. The fellow, dressed in street clothes, jumps higher and higher, at the urging of Carson, only to leave camera range and not return.

"Who Do You Trust"

Permanent national attention came when Carson hired-on to host another game show, "Who Do You Trust?" That was 1957. The new show meant a move to New York City.

The title of the show is grammatically incorrect. It should be "Whom Do You Trust." As is often the case, with media content, an error can be a good hook.

About "Who Do You Trust," Roy Kammerman, head writer of the show, said, "It was a version of 'You Bet Your Life,' hosted by Groucho [Marx], aimed at a mass day time audience ...." The Carson show ran at 3:30 pm, weekdays. "You Bet Your Life" ran weekly and 9:30 pm. Groucho got away with a lot more than did Johnny.

The formats of "You Bet Your Life" and "Who Do You Trust" were almost identical. Carson would talk with two guests, who most often didn't know each other. He'd drop a few, mostly cutesy, if risqué, comments that kept the ears of the NBC censor perked. Once he'd wrung the guests dry or it was time for a commercial, Carson would ask an inane question, "Who's buried in Grant's tomb," and give each a small prize for the correct answer. The economics of reality television aren't new.

As with most game shows, of the time, the point was the fun of the exchange. An accident-prone contestant says he got his hand caught in a woman's blouse on a crowded subway. Carson replies, "You were getting a hold of the wrong strap ... weren't you?" For Carson, it was a tune up for the "Tonight Show." Already quick on his feet, he had plenty of practice, five days a week for five years.

"Who Do You Trust" ran on ABC from 1957 to 1963, when Carson left for "Tonight." Bill Nimmo was the first announcer on "Who Do You Trust?" Ed McMahon (1923-) replaced Nimmo during the first season, staying until 1962. Del Sharbutt and Woody Woodbury split announcing duties during 1962-1963, the last season.

Carson met McMahon on "Who Do You Trust?" The calm, conservative McMahon was the perfect foil for the edgy, acerbic Carson. They worked together, continuously, for the next 35 years, always successfully.

Doc, Johnny and Ed

"Tonight Show"

The "Tonight" show was the creation, in a sense, of Pat Weaver (1908-2002). In 1952, Weaver headed NBC television programming. He wanted a late night companion for "The Today Show."

Early on, Weaver recognized these shows as bottomless pits of money for the networks. Each is inexpensive to produce. Each is popular. Each attracts a long list of advertisers, willing to pay premium prices. Live to air, "Today" and "Tonight" were the first reality television shows.

Weaver, above father of actor, Sigourney Weaver, wanted to take a local New York City show, "Broadway Open House," national. Host Jerry Lester was too raucous, NBC believed, for a national audience. Steven Allen, an underused, underappreciated satirist, had a similar show on WCBS-TV. In late 1953, Allen moved his local show to the NBC affiliate in New York City. On 27 September 1954, Allen went national. Weaver (right) dubbed the Allen show, "Tonight," to align it with "Today."

Allen preferred skit comedy and jazz to guests. His ensemble included Pat Harrington, Don Knotts, Louis Nye, Bill Dana, Dayton Allen and Tom Poston� The announcer was Gene Rayburn, of "Match Game" fame. When it came to guests, Allen didn' toe the line. Allen accompanied, Jack Kerouac, the Beat Writer, who's performing spontaneous prose. Kerouac was considered too radical for television, at the time, but Allen didn't care. It was a rare chance to play some cool jazz with the coolest guest.

In 1956, NBC added a weekly prime-time show for Steve Allen, against Ed Sullivan on CBS. Ernie Kovacs (1919-1962), an influential humorist, hosted "Tonight," Mondays and Tuesdays. This gave Allen time to prepare his Sunday show.

At the end of the season, Allen declined to return to "Tonight." Kovacs declined to take over, full-time. This was a new challenge for NBC.

Weaver spent the 1957 season trying new approaches. He changed the name of the show to "Tonight! America after Dark," and tried different formats. Nothing worked. The Allen format had the legs. In July 1957, the show went back to the original name, "Tonight," and format. The new host was Jack Paar.

Paar came to public attention as host of a summer replacement series for "The Jack Benny Show." Paar was more cerebral and melancholy than Allen, whose optimism often over-shadowed his talent. He firmed up the presence of "Tonight," among viewers and advertisers.

Allen made the late-night time slot viable. Paar made it prominent. Carson made it influential.

Viewers stayed up late, to watch Paar (above). Actor and raconteur, Peter Ustinov, told memorable stories. A drunk Judy Garland raged about Marlene Dietrich. At a party she attended, said Garland, Dietrich played only the applause from live recordings of her recent European tour. During the 1960 US Presidential Election, John Kennedy (1917-1963) and Richard Nixon� appeared separately. Paar was first to interview Robert Kennedy, following the assassination of John F. Kennedy, in 1963. "Tonight" set the agenda of water-cooler talk.

Paar preferred intelligent, literate conversation, Judy Garland not with standing. A huge number of viewers did too. While Paar hosted "Tonight," the audience grew tremendously. Sales of television sets, more and more were second sets, continued to soar. This was in part due to Paar. Viewers were fascinated with him. He never talked down to them. As restless and emotive as he usually was, viewers stayed with him.

On 11 February 1960, the ever-volatile Paar did his monologue and promptly walked off. The NBC censor had cut a skit about "water closets," an old, polite term for bathroom. The next night, as Paar ended his monologue, he said, "I've made a decision about what I'm going to do. I'm leaving 'The Tonight Show.' There must be a better way to make a living than this, a way of entertaining people without being constantly involved in some form of controversy. I love NBC ... but [it] let me down." Announcer Hugh Downs was left to host the show.

A few weeks later, Paar returned. He opened his first monologue, saying, "As I was saying before I was interrupted ... I believe the last thing I said was 'There must be a better way to make a living than this.' Well, I've looked ... and there isn't." The love affair of Paar and his viewers resumed.

As Steve Allen, before him, Paar moved to prime time on NBC. His last "Tonight" show was 29 March 1962. April through October, when the Carson era began, "Tonight" had a series of guest hosts, most of whom were Groucho Marx.

"[Steve] Allen," writes David Edelstein, "was a fundamentally earnest presence ... Paar was, if anything, over earnest (to the point of bathos) ... [and] Carson was cutting. There was ... a chill behind the twinkle. If [Carson] cultivated the look of a boyish Midwesterner (he certainly played up his Nebraska roots), he could change into a bad boy (or a smutty-minded boy) in an instant." As derisive as David Letterman (1947-), another Midwesterner, Carson was more subtle. A raised eyebrow, writes Edelstein, or a sidelong glance put an unruly guest in his or her place. "The reason his [approval] was so treasured," decides Edelstein, "was because it was so hard to win."

On Monday, 1 October 1962, Carson began hosting the "Tonight Show." Contractual issues kept him from taking over earlier. "Who Do You Trust" was a reliable and steady source of substantial revenue for ABC-TV, the also ran of the networks, until the 1970s. Carson fulfilled his obligations to ABC. Then he moved to NBC.

"He seemed relaxed about the move," says Stan Klees, who met Carson in August 1962. He showed no hint of what was to come and seemed most happy to have a better job. "He was warm and pleasant, [standing] at our table for quite a while," says Klees, co-founder, with Walt Grealis, of the Juno Awards. "We talked about his new job, and he was confidently anxious. He asked what I did in Canada, and seemed genuinely interested in my work.

First Carson "Tonight" Show

On the first show, an unbilled Groucho introduced Carson, and was the ex-offico sidekick. NBC executives, writes Stefan Kanfer, "flirted with the idea of Groucho as the [full time] host." In the end, everybody agreed the five-day a week grind was too much to expect of a 72-year-old man, and NBC went with Carson.

The "Tonight Show" remained in New York City, when Carson took over. Studio 6-B at Rockefeller Centre was its home. New York City was the hub of the entertainment industries and guests were plentiful. The show taped weekdays, around 5:30 pm, a convenient time for guests appearing on Broadway or in local clubs. The show aired after 11 pm, local time, across the country. Carson tucked a nation into bed. (Right, Carson, with the original co-host, in early publicity photograph for the "Tonight Show"; left with Rudy Vallee on first show.)

Audience response to Carson was tremendous. He quipped, "Boy, you would think it was Vice-president Nixon." The studio audience knew what the rest of the country would soon find out: they'd found their voice. For 29 years, 7 months and 21 days, Johnny Carson spoke the mind of America.

In his first, of about 4,500 monologues, Carson said he knew he was taking over the show for about 9 months. He did 150 interviews about the new job. The guests were amazing, he said, Groucho, who had subbed as "Tonight Show" host for several months, Rudy Valle, Joan Crawford, Mel Brooks and Tony Bennett. A stronger opening line-up was not possible. The back stage excitement, he said, was infectious and nerve wracking. "Put all this together," Carson concluded, "and all I can think of is, 'I want my nana.'

After originating from New York City for 28 years, the "Tonight Show" moved to Los Angeles,  in 1972. About the same time, the start time standardized at 11:30 pm and Carson cut back to four days a week. (Right, Ed McMahon and Carson talk before the first skit or guest.)

in 1972. About the same time, the start time standardized at 11:30 pm and Carson cut back to four days a week. (Right, Ed McMahon and Carson talk before the first skit or guest.)

Mondays were now for guest hosts. The top eight "Tonight Show" guest hosts are Joey Bishop (177 shows), Joan Rivers (93), Bob Newhart (87), John Davidson (87), David Brenner (70), McLean Stevenson (58), Jerry Lewis (52) and David Letterman (51). (Right, Ed McMahon and Carson about 1973.)

Joan Rivers (1933-) was the permanent Monday night host from 1983 to 1986. After a few months of rotating guest hosts, Jay Leno (1950-) was picked as the new permanent Monday night host, in 1987. Leno, the Monday night jokester, was a good lead in to a week of Carson satire, skits and guests.

Leno took over the "Tonight Show," full time, when Carson retired in 1992. "NBC," Carson told second wife, Joanne, "needed somebody they could control." Leno, not David Letterman, was the natural choice.

NBC and various hosts tried tweaking the structure of the "Tonight Show." Yet, the format remained the same: monologue, sketches, interviews and a performance guest; a musician, with a new record, or a comic. In 40 years, the only major change came in 1980, when the "Tonight Show, starring Johnny Carson," went from 90 to 60 minutes. About the same time, the standard start time moved to 11:35 pm, giving local stations a few more minutes for lead-in commercials.

NBC was and remains hard-pressed to fiddle with the "Tonight Show" format. In 1978, reports Laurence Learner, the show accounted for "17 percent of the profits of NBC." At contract renewal time, writes Learner, NBC executives, who could give lessons on deceit, treachery and cruelty to Vlad the Impaler, prostrate themselves before Carson. They sob as scared children. "Forgo retirement," they plead. "Here are millions of dollars for you and deals for your production company. Please continue to host the 'Tonight Show.'"

Fred Allen, the topical radio satirists of the 1930s and 1940s, was also a hero of Carson and best friend to Jack Benny. (Above, Allen, right, with Benny in late 1930s.) Talking about network executives, Allen said, "Nobody knows what they do. On ships, they're called barnacles." Carson likely agreed. (Left are Jack Benny and Fred Allen, about 1936, when their famous radio feud began.)

At first, Ed McMahon introduced the show is a standard way. Soon the "Heeeerrre's Johnny" introduction took hold. "Heeeerrre's This" or "Heeeerrre's That" is a mainstay of introductions, 45 years later.

Golf swing ends the monologue

The quick, intelligent wit of Carson was compelling, as was his charm. Viewers eagerly anticipated his opening monologue: the worse, the better, the funnier and, often, the more meaningful. A bad joke, in the monologue, might elicit groans from the "Tonight Show Band," studio audience and 20 million women and men across the US and Canada. A particularly bad joke could lead to an impromptu bit of soft-shoe, to the music of "Tea for Two," or Carson taking the boom microphone and blurting, "Attention, K-Mart Shoppers! In aisle 34, we're featuring 30% off toilet paper." The monologue ended with Carson mimicking a golf swing and the band breaking into the "Tonight Show Theme."

Rarely tasteless or crass, Carson monologues wrapped serious points in groaners and "Tea for Two" jokes. Each taping day, the "Tonight Show" writers supplied Carson with jokes. "He selected and edited the jokes, by himself," writes Mark Evanier. Once he had the jokes, the writers were out of the picture. [Carson] rephrased some, added a line or two of his own, and then the monologue went directly to cue card person. "You could," writes Evanier, "... spot the new guys on the writing staff, sneaking [around the cue card area] ... trying to get a look at the cards, trying to recognize their jokes." If you didn't make the cards once a week or more, you were looking for a new job.

Carson had total control of the monologue. He could hide biting satire among the groaners, and did. Each monologue was Carson speaking the mind of America.

His monologues were topical, and now toothless out of context. The satire of, "Nancy Reagan fell down, and broke her hair," is lost in 2007. In 1983, it pointed to the dated primness of the First Lady and, perhaps, the tired policies of the Reagan presidency.

"I was so naïve, as a kid," said Carson, "I used to sneak out behind the barn and do nothing." Today, the comment shoots passed viewers. The notion of sneaking out behind the barn to smoke, look at naughty pictures or have sex isn't part of the urban pop culture. Under the highway overpass or at the mall might work today.

Only the oldest oldsters, today, would get his response to moans from the audience, after an especially bad joke: "You didn't boo me when I smothered a grenade at Guadalcanal."

On 25 January 2005, two days after Carson passed away, David Letterman performed a four-item monologue written entirely by Carson. In 2005, the material was on the mark and topical. In a sense, here's the final Carson monologue.

"This is a sad story. Paris Hilton has a dog named, Tinkerbell, and Tinkerbell went missing. But don't worry. They found Tinkerbell. Tinkerbell was with the Taco Bell Chihuahua making a sex video.

"How many of you people are on a low-carb diet? Everything is low-carb now; they make low-carb beer, low-carb pizza and low-carb ice cream. But, I was reading in the Times, and this makes no sense to me, you can buy low-carb condoms.

"John Kerry was criticized for throwing away his military medals, back in the 70s. Not to be outdone, President Bush threw away his National Guard spotty attendance ribbon.

"President Bush stopped in Canada, where he received a cool reception. But, on the bright side, he was able to stop in a pharmacy and fill his prescriptions."

Carson made four satirical statements, in these "jokes." He pointed to the inanity of pop media culture. Made you think about your health, your fad diet. He directly pointed to the shameless actions of a leader, who sentences young women and men to needlessly early death or a life of suffering. Finally, he linked poverty, old age and illness, exposing exploitation by pharmaceutical companies. Few people can do so much with 132 words. Carson did it for almost eleven thousand nights. He got billions and billions of laughs, telling viewers what they needed to know, wrapped in groaners.

The monologues, delivered with his casual Midwestern style, were sharp, cool and influential. "The Great Toilet Paper Shortage" was a Carson joke gone wild. During the 19 December 1973 monologue, he said, "You know what's disappearing from the supermarket shelves? Toilet paper! There's an acute shortage of toilet paper in the United States." The next morning, his 20 million viewers bought all the toilet paper they could find. By noon, many stores were out of stock. Demand quickly wiped out supply. There were attempts to ration toilet paper.

There were many shortages in the 1970s. The response was only half-foolish. Later in the week, Carson apologized, explaining it was a joke by a staff writer, "who just got a huge raise in pay." Carson was able to diffuse problems, with his quick wit and sense of silliness.

In the tradition of Steve Allen, Carson featured recurring bits and characters. "Carnac the Magnificent," above, was a psychic, who, like "Jeopardy," gave questions to answers. The character played out this way. Carnac holds the sealed envelope up to his turban and says, "Green Acres." Sidekick, Ed McMahon responds, "Green Acres?" Carnac gives McMahon a faux derisive sidelong glance. Carnac tears open the envelope and takes out a card, which reads the question. "What Kermit has after Miss Piggy kicks him in the groin?" Ed McMahon told Larry King (1933-) that his favourite Carnac answer was, "Sis boom bah," which answers the question, "What's the sound made by exploding sheep."

Another popular character was Art Fern, the host of the "Tea Time Movie" skits (above). Afternoon movies were the mainstay of early television. Local stations inserted as many commercial breaks, as possible, often extending a 90-minute movie to three hours. During the breaks, a local announcer would flog products. Art Fern was the classic afternoon movie host, who flogged an endless array of inane products. As with all archetypes, sadly, there was too much truth in the Art Fern character. Fern had an assistant, "The Matinee Lady." Over the years, Paula Prentiss, who set the statuesque standard, Carol Wayne and Teresa Ganzel, portrayed "The Matinee Lady." Above is Carson as Fern, with "Tea Matinee Lady," Teresa Ganzel."

Typically, Fern would promote an up-coming movie, deliver a convoluted commercial, introduce the movie, show a one-second clip and come back to another commercial. The fake movies included, "Dracula Gets Bombed on a Wino, with Jack Lemon, Jack Haley, Haley Mills, The Mills Brothers, Dr. Joyce Brothers and Spawn, the Wonder Carp!" Across the USA and Canada, most local televisions stations ran a reality version of the "Tea Time Movie."

Carson romaing audience during "Stump the Band";

bandleader, Doc Severinsen, right

Standard bits, such as "Stump the Band" added another layer of variety to the "Tonight Show, starring Johnny Carson." Jack Paar used a version of "Stump the Band," which suffered from unimaginative audiences and knowledgeable musicians. Members of the Carson "Tonight Show Band," lead, variously, by Skitch Henderson, Milton DeLugg and Doc Severinsen, almost never knew the song, and the humour was in their improvisation.

One night, Carson roamed the audience, asking for song titles to "Stump the Band." There was a request for "My Dead Dog, Rover." Instantly stumped, Severinsen came up with, "My dead dog Rover, lay under the sun, and stayed there all summer, until he was done"; the band played along and laughter filled homes across the USA and Canada. (Right is Doc Severinsen.)

Carson played well everywhere, but his studio audiences were mostly tourists from the Midwest. He'd roam the audience, playing an inane game, asking contestants what their name was and where they were from. Most often, they were from Omaha, Cedar Rapids or another Midwestern city.

Carson had a clear Midwestern tone. He always scorned deception, as >when he colluded with James Randi, above,to expose Peter Popoff and other televangelists. He deflated the pompous and self-important, never guilty of these transgressions himself. He enjoyed the humour and comfort animals offered. Joan Embry, of the San Diego Zoo, and Jim Fowler, of "Wild Kingdom," were favourite guests. It was a poem, written and read by actor, Jimmy Stewart, about his dog, "Beau," which made Carson cry.

No social issue escaped Carson. He grumbled about taxes, hangovers and former wives. Politics and politicians were fair game. He liked to mimic Ronald Reagan and often relentlessly pressed candidates, brave enough to guest on the "Tonight Show."

"In a way," says religious scholar, Kathleen Riddell, of McMaster University, in Hamilton, Ontario, "Carson was civil religion. Millions, not only Americans, shared his Midwestern ideals of family and hard work. They attended his televised services. They made the pilgrimage to his shrine, the NBC Studios, in Burbank." Unlike many modern religions, Carson didn't ask for donations, only a moment to linger on his words and ponder what he said.

The "Tonight Show" was a rites des passage for comedians, struggling to build a career. "You had to be careful," says Howard Lapides, a Los Angeles-based manager and producer, "about doing Carson. If he liked your work, you'd get re-booked, on short notice.

>

>

"A booking on Carson meant you had to have two sets ready to go; three was best. A month isn't long enough to work up a second, 'Tonight Show' quality set," says Lapides. "Putting material together that fast, is asking for trouble. If they did, they'd suffer what I call the 'Second Shot Syndrome.' If a comic didn't shine, on the second booking, he or she doesn't come back, again." (Above, left Richard Lewis, a frequent guest on the "Tonight Show.)

During an appearance, in the late 1980s, Steve Martin (above, left, about 1970) jabbed at the "Second Shot Syndrome." Carson noted Martin hadn't been on the show in a long time. Martin complained he always had to have new material to get booked on the show. "Can't even use a better version of something I did here 5 years ago," complained Martin.

Howard Lapides implies another Midwestern value Carson embraced. If you're going to do a job, get it right. Have the second or third set ready to go. Carson expects you do. It's good advice, too often mislaid, today, which Carson enforced.

Carson was a taskmaster. Mark Evanier, a comedy writer, explains the high turn over rate of "Tonight Show" writers. "A friend," he writes, "worked for Carson for 20 weeks; it was the best and worst of times.

"The reason Johnny's been on so long," writes Evanier, "is that he treats every show like everything's riding on it. He figures he has to be at his best every night, so everyone who works for him has to, as well. Everyone has a job to do. If you do your job, everything's fine. If you don't ... well, the only time you'll ever see Johnny get mad is when he feels someone isn't doing [his or her] job. Because he figures he's the one on the spot without the proper support."

The cream of the crop performed on The Tonight Show, starring Johnny Carson." Comedian, Wil Shriner, above, guested often on Carson. These days, Shriner (right) is a movie and television director. In 2006, he wrote and directed the movie, "Hoot." His television credits include "Gilmore Girls," "Everyone Loves Raymond," "Frasier" and "Becker," among others. He also starred, with Nicholas Cage and Jim Carry, in "Peggy Sue Got Married."

Shriner has warm memories of Carson. "Johnny was the best. He was the reason many of the young comics stayed clean with their material, so they could get on Carson.

"[The 'Tonight Show'] was the one and only show, at the time, and it meant you had made it as a stand up. I emulated Carson, and when I had my own show, he was [who] I looked at and studied. He was a great listener and a great host.

"His material didn't matter. Good or bad, Carson made it work. When he had to, he was a genius at savers.

"I knew [Carson] socially," says Shriner, "through my manager, Bud Robinson, who handled Doc Severinsen. I'd go up to Bud's, early, on their famous poker night, just to be around him; he was very shy in private. He's a hero of mine, forever. And to sit on the "Tonight Show" panel and make him laugh was one of the high points in my career."

Success was making Carson laugh, and few did. An honour, for any performer, was to please Carson to the point he'd ask them to join the panel. Either feat typically meant a second booking, in short order; both confirmed star status. Carson was the gatekeeper on the road to success as an entertainer.

Personal Life

Family life for Carson was decidedly not Midwestern. He married four times. Comments about break ups, alimony and the demands of former wives littered his monologues.

Carson and college sweetheart, Joan Wolcott, got a "quickie Mexican divorced," in 1963.

Carson married Dr. Joanne Copeland, in August 1963. They divorced in 1972. After a drawn out negotiation, Copeland received $500,000 cash, an art collection and $100,000 a year, for life.

At a party, on 30 September 1972, celebrating the tenth anniversary of the "Tonight Show, starring Johnny Carson," he and Joanna Holland (1941-) announced they'd married that afternoon. They divorced in 1983. Holland received $20 million cash and other property; "money couldn't heal her feelings or assuage the pain," writes Learner.

The financial burden of divorce was a theme of his life and monologues. In a monologue, just after Christmas, 1982, Carson said, "My producer, Freddy de Cordova, gave me something I needed for Christmas ... a gift certificate to the Law Offices of Jacoby & Meyers." Carson told reporters he repeatedly married women with similar first names so he didn't have "to change the monogram on the towels." Supposedly, the morning after Bob Newhart repeated this line, at a televised Carson roast, Holland filed for divorce.

Carson saw Alexis Maas walking by his Malibu Beach home, one evening, carrying an empty wine class. She'd allegedly talked a guard into letting her on his property. He went out to meet her, carrying a bottle of wine, and supposedly said, "Can I fill you up?" They married on 20 June 1987. It was his longest and, presumably, happiest marriage. If nothing else, it broke the "Joan" jinx.

As an aside, the Carson beach home, on Wildlife Road, in Malibu, CA, sold for a tad under $40 million US, in March 2007. The buyer, Sidney Kimmel, Chairs Jones Apparel and produced movies, such as "Breach," "Alpha Dog" and "United 93." Apparently, the price is high, even for Malibu.

Not All Laughs

"The Tonight Show, starring Johnny Carson" had serious moments. Toward the end of his marriage to Holland, Carson confronted tabloid gossip about the marriage. After the monologue and first commercial break, he held up a copy of the "National Enquirer." An article, in the magazine, asserted his marriage was "on the rocks."

Ice-cold, Carson looked squarely into the camera, saying, "I have not seen this until this morning. Now, before I get into this or say any more, I want to go on record right here in front of the American public because this is the only forum I have. They have this publication; I have this show. This is absolutely, completely, 100 percent falsehood ... I'm going to call the "National Enquirer," and the people who wrote this, liars. Now that's slander. They can sue me for slander. You know where I am, gentlemen."

The "Tonight Show" was a platform for him to set the record straight. As truth is the defence against slander, Carson felt safe. The tabloid didn't sue, but continued to print stories about him. A few months later, he and Holland divorced.

In 1984, Carson sued the "National Enquirer," for $51 million. The item at issue was, 'Johnny Settles - Huge Payoff for Joanna as Bitter Divorce Battle Ends.'" Carson ostensibly didn't like the idea Holland had won a huge divorce settlement. The "Enquirier" reported Carson settled with Holland for $32 to 42 million. The amount, as it turned out, was $20 million.

Satire

Carson performed his most memorable monologue on 11 September 1991. The topic is democracy. The title is, "What Democracy Means to Me."

As the "NBC Orchestra" played, gently, the "Battle Hymn of the Republic," Caron said, "Democracy is buying a big house you can't afford, with money you don't have, to impress people you wish were dead. Unlike communism, democracy does not mean having just one ineffective political party; it means having two ineffective political parties. Democracy is welcoming people from other lands, and giving them something to hold onto, usually a mop or a leaf blower. It means that with proper timing and scrupulous bookkeeping, anyone can die owing the government a huge amount of money. Democracy means free television, not good television, but free. Finally, democracy is the eagle on the back of a dollar bill, with 13 arrows in a claw, 13 leaves on a branch, 13 tail feathers and 13 stars over its head. This signifies that when the White man came to this country, it was bad luck for the Indians, bad luck for the trees, bad luck for the wildlife and lights out for the American eagle. I thank you."

These ideas aren't new. Any course in civics covers these ideas. Others satirists have expressed these sentiments: Groucho, with style; Bill Hicks, with force; the late Richard Jeni, calmly. The authority, the effect, lies in who says what, when, where and how.

Carson spoke to an audience of 20 million. He spent 30 years developing trust and confidence. The connection was intimate, more akin to radio than television.

When Carson spoke, viewers listened, as if it was their best friend. His words lingered; pondered by viewers. The results were satirical, and effective. Carson spoke the mind of America.

The monologue is frank. The style is open, honest and warm. Unexpected, perhaps, is the blunt liberalism.

Carson long hinted he was more open minded than he let on. He beamed, almost gushed, when Hubert Humphrey guested, in 1968. His send up of Bill Clinton, in 1988, was an obvious stamp of approval. Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon evoked respect, admiration and acute interest, but not approval. This monologue cinches the fact.

Retirement

After years of teasing, Carson retired from the "Tonight Show," on 22 May 1992. The ins and outs of his retirement are beyond fair discussion here. Still, a few points are worth noting.

Clearly, Carson had five or more good years left. Healthy, though a life-long chain smoker, he was intellectually acute and physically active. He was sharper and quicker than were any of his competitors. He played tennis, daily, and traveled widely, with Alexis, something he hadn't done much before he married her. (Right, at Wimbledon, in 2001.) He drove himself 40 miles to and from work. "That's a nice 40 mile drive," says Howard Lapides, "from Wildlife Drive, in Malibu, to the NBC studios in Burbank." Nice, but still an hour each way or more, which Carson did with ease.

All around, Carson was active and able. Three live shows a week seemed a fair grind. Larry King and Regis Philbin, at 74 and 76, flourish on network television. Ed McMahon remained active until 85.

The "Tonight Show" structure was stable, the audience growing. Carson, McMahon and Severinsen (above) fit as a glove. Agitation for change came mostly from those wishing to replace Carson, on the "Tonight Show," except David Letterman.

Carson acted on the notion that discretion is the better part of valor. He opted to retire, on his own terms. He was dignified to a fault, and to the end. A lesser person likely would've gone kicking and screaming into the long dead air, and tried to make a comeback.

By 1992, Carson was working on yearly contracts. He seemed fine with the arrangement. More money surely accompanied each renewal. In the end, his fierce independence likely didn't sit well with NBC executives. Though no one talks, on the record, Carson may have preferred to stay a few more years, but NBC wanted the show back.

Some markers point to the ouster of Carson. He declined the offer to retire in prime time, with lots of big name celebrities and ballyhoo, preferring to leave as he came, on the "Tonight Show." Usually a team player, Carson didn't retire in a way that would most benefit NBC, and Leno. Fifty million people watched the last "Tonight Show." The audience for a prime time retirement party might have been the most watched television show, ever. He declined to let NBC benefit thrice: him out, replaced by a controllable host and a huge prime-time payday. This is telling.

Carson didn't guest on the "Tonight Show," after he retired. Jack Paar and Steve Allen guested, often, on the show after leaving. Carson (right) made an "unscheduled" appearance on "Late Night, with David Letterman," in 1993. He went so far as to sit behind the desk. There was also a brief cameo on "Letterman," in 1995. The inaction and action are telling.

Carson wisely stayed out of the selection process for his successor. It's likely NBC< preferred it that way. Unofficially, he advised Letterman, but not Leno. As permanent guest host, Jay Leno had an advantage, but not the seal of approval.

Carson had told second wife, Joanne Copeland, NBC wanted somebody it could control. Leno was the obvious choice, to replace Carson, on the "Tonight Show." Letterman, compared with Leno, was a loose cannon, creatively.

The cover of "Rolling Stone" magazine was the seal of approval for Letterman: he's heir to Johnny Carson. Nobody got anything from Carson, without hard work, Letterman earned the approval.

The Final "Tonight Show, starring Johnny Carson"

The last episode of "The Tonight Show," Carson said, was a time to reflect. "There'll be no performances," he said. Just many thanks.

The monologue was brief. Its topic was Dan Quail, then Vice-President of the USA. Carson said it was too bad he was retiring because Quail was providing so much good material.

After George F. Bush lost the Presidential election, in 1992, Bill Hicks echoed Carson. Performing at the Oxford Student Union, Hicks expressed how happy he was Bush lost. After a pause, he said, "but I shouldn't be so %$#@ing happy 'cause, with Bush gone, I've lost half my act."

The audience for the final "Tonight Show, starring Johnny Carson" was comprised of invited family and friends of the production staff. Wife, Alexis, was in the audience as were his sons, Kit and Cory, his brother and sister, and their families. There was a moment given to his son, Richard, who'd died in a traffic accident. He apologized to Kit and Cory for not "being there" for them, and told them how much he loved them. Then the monologue was over. The band launched into the "Tonight Show Theme," with unusual power. Carson gave one last faux golf swing into the commercials.

After the break, there's farewell repartee, with Doc and Ed, before clips of memorial guests, Jack Benny most prominent. A brief documentary, about the stage preparations for a show, a chance to show off-camera staffers, follows the second commercial break. After a third break, comes a photo-scrapbook, featuring guests and special moments. Carson doesn't mention that son, Richard, took many of the photographs. As the stills repeat a lot of the video scrapbook, the homage to Richard is obvious.

Back in the monologue spot, Carson offers a final statement. "And so it has come to this. I am one of the lucky people in the world. I found something that I always wanted to do and I have enjoyed every single minute of it. I want to thank the gentlemen who've shared this stage with me for thirty years, Ed McMahon, Doc Severinsen, and you [who are] watching. I can only tell you that it has been an honour and a privilege to come into your homes all these years and entertain you ... I hope when I find something that I want to do, and I think you would like, and come back, that you'll be as gracious in inviting me into your home as you have been. I bid you a very heartfelt goodnight."

The "retirement" show, tellingly, was about everybody, except Carson.

Final Performance Show

The final performance show was 21 May 1992. Robin Williams and Bette Midler guested. Williams, obviously honoured, contained himself, a bit. The final "Tonight Show, starring Johnny Carson" performance was Midler singing, "One for My Baby" to a tearful Johnny, one of his two favourite songs.

Earlier, Midler sang and "camp-ed" a cabaret poem for Carson. The poem is worth reproducing. It reveals more about Carson than anything else.

"Dear Mr. Carson," sings Midler, "I'm writing this to you. I hope you'll read it, so you'll know, my heart goes pitter-patter, and I stutter and I stammer, every time I see you your TV show. I guess I'm just another fan of yours, and I thought I'd write and tell you so.

"You made me watch you. I didn't want to do it. Jack Paar had put me through it. You made me watch you.

"I love the jokes you're flogging, when you're monologuing. I watched your hair turn, slowly, from dark to white. When I can't sleep, I could your ex-wives at night.

"I'd drop my drawers for the kind of bucks you're making for simple double-taking. Before you bid adieu, don't' be cheap, put de Cordova to sleep. [de Cordova was the "Tonight Show" producer and director.]

"Just the thought of your leaving me, gives me the shivers. Arsenio’s at the gate, and so is Joan Rivers. You know they make me watch you.

Ah gee,” she camps, “Mr. Carson, I don’t want to bother you. It’s just that when I heard you were leaving, well, it kind broke my heart. I mean, I can’t tell you how many nights I laid in bed, watching you, thinking to myself: should I change the colour of my toenail polish?

“You know, Johnny, I got to tell you, you’re the greatest straight man that ever walked the earth, and I’ve known my share of straight men.

“I got to ask you, though, ‘Johnny, what are you going to do with all that free time?’ I mean, Wimbledon comes only one week a year.

“And did you ever stop to consider what’ll become of [slight pause and drops voice] ‘Ed,’ not to mention Doc, and [slight pause and drops voice] ‘the band.’

“Well, maybe I’m just being selfish, because, after all, my life is going to change the most. I mean, how am I going to get by without you – you sexy thing – your charm, your wit, your talent, your civility and all your fabulous, fabulous guests?

“How I’ll miss,” Midler sings, “the social intercourse, so varied. Now I have to have it with the guy I married. You know I’d rather watch you.”

The “poetic” style, at first, seems unlike Carson. It’s too New York, too ethnic, too off-Broadway, too camp, too liberal. As Midler emotes, you realize Carson’s thoroughly enjoying it. Then you remember he gave it the go ahead, as he did all “Tonight Show” content.

Midler relays what Carson wants us to know about him. He’s intelligent, open minded and has a strong sense of his image and purpose. Nothing sums 30 years of the “Tonight Show, starring Johnny Carson” as effectively, efficiently or lovingly as Midler singing and camping.

Carson and Midler also sang an impromptu duet of “Here’s that Rainy Day,” one of his two favourite songs. His other favourite song was “I’ll be Seeing You,” which Steve Wonder had performed for him in February. More evidence to the point made by Steve Parker, “The Car Nut,” that the final weeks or months were good show business, planned to finest detail.

“Carson was the last of the Steve Allen line,” says Dick Summer, who currently hosts a syndicated podcast, “A Good Night’s Sleep,” and you see it in the last two shows. “You could trust him to be there, even in your bedroom. You knew he’d share some laughs with you, while pretending he didn’t notice the woman in bed with you, until he gave you one quick wink, just before “Doc” started the theme music out. Leno [is a] comedian. Carson was Carson, the ultimate pro, always in control, until that single tear, at the very end, showed he was even more human than we ever knew. I loved [him]. You did, too. Carson was you and me, the way we wished we could be.”

We Heard the News, Today, "Oh, Boy"

Johnny Carson passed away at 6:50 am, on 23 January 2005. He was 79. The cause was emphysema.

At his request, his remains were cremated, and there was no public memorial service. The biggest mega-church wouldn't have held the family and friends of Johnny Carson. The throng of mourners, maybe more than a 100 thousand, would've caused chaos for blocks around the site of his memorial. Carson certainly knew it'd be a spectacle, and didn't want to cause a fuss.

More to the point, perhaps, he didn't care much for funerals. In the mid-1980s, about the time his mother, Ruth, passed away, Carson took a comment by guest, Dr. Ernest Dichter, the motivational researcher, as the chance to criticize the fact and business of funerals. His comments were harsh. Funeral directors likely still cringe from his anger.

Countless tributes arrived. Long, mostly glowing obituaries dominated all media. Those who “knew” Johnny paused and reflected for a moment or ten.

On the “News Hour, with Jim Lehrer,” for 24 January 2005, spoke of Carson, with eloquence. He noted Carson wasn't the guy at the party with the lampshade on the head, dancing around on the coffee table. He was the witty guy, on the couch laughing [with] that person. Carson really became a star reflecting the performances of other stars, and it's why we could not get sick of him for 30 years. He was a born showman. He was studying it when he was a kid. He wrote a thesis at the University of Nebraska on Jack Benny and timing, I think it was. And he was nice to have in the room with you.”

A Public Man

Most of what we know about Carson is public knowledge. Even ostensible insights about Johnny Carson, the man, are public and thus suspect. Ed McMahon travels America, with a show called, “A Tonight Show Evening,” that allows him to talk about Carson, the show, the guests and the fun. The McMahon show is a fitting tribute to Carson, but reveals little about the man.

This is expected. Carson was a public man, most comfortable, it seems, working an audience. Insights about the private Carson are few, but here are some.

Howard Lapides met Carson twice. “The first time, ”he says, “was in Atlantic City, about 1980. Paul Brownstein, Geoff Fox and I were at a Carson show. Always somehow connected, Paul got us invited to join Carson, in his suite, after the show.”

The second meeting was in 1989, says Lapides. “I was at the “Tonight Show,” with a friend, Richard Jeni. Coming out of the dressing room, I met Carson. He was coming up the stairs from his office. I introduced myself and reminded him we’d met before, in Atlantic City. I’m sure he didn’t remember, but acted as if he did.

“Both times [I met Carson], he was warm, genuine to a fault.”

A blogger, named SJ, posted a revealing antidote about Carson, on TMZ for 8 March 2007. "I remember, says SJ, "moving to LA about the time Johnny retired (1992). I was out very late, [my] first night in town. When we stopped for gas [at a station in] Santa Monica, this wicked ghost white Corvette [pulls] into the pumps beside of us. I was admiring the car for a few seconds before I realized that Johnny Carson was getting out, to pump his own gas." A simple act says much about a great man.

“After Johnny took ill,” says Steve Parker, “The Car Nut,” I had an unusual ‘personal’ experience with him.

“I was admitted to St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica, CA, on the same day Carson was discharged. I was wheel-chaired down a long, underground tunnel. At the other end of the tunnel, about 200 feet away, I could see a small group of people huddling around a wheel chair.

“As we approached, they turned and headed towards us. Carson was sitting in the wheel chair. I knew he’d been in St. John’s. Now, here he was in that wheel chair coming my way.

“Almost everyone in the group, of 6 or 7, was crying. Carson was not. “As the group approached, I could see he Johnny looked gaunt, pale and gray. As he came closer, I realized that now might be my opportunity, perhaps, to cheer-up Johnny, as he had done for my family and me countless times.

“As we passed, two guys in wheelchairs, Carson heading for an exit, me heading for my room, I gave him a “thumbs up” signal and said, “Hang in there, man!”

“Damned if Johnny didn’t smile as he passed, sick as he was.

“He didn’t die for many months after that meeting. It was a strange, very personal and satisfying experience for me, and I hope for him, too. Who knows? Maybe some stranger offering encouragement, in a hospital tunnel, helped Johnny Carson keep going for even one more day.” Carson built strong ties, with viewers.

Larger meaning always flows from small details. Howard Lapides knew the civil, warm and classy Carson. Desperately ill, perhaps aware more intervention was useless and heading home, for the last time, Carson had a moment to thank Steve Parker, with a brief smile. Habits, maybe, bred of the Midwestern ethic and a full life in the limelight, Carson confirmed the graciousness we saw nightly on television, that Stan Klees had felt 45 years earlier, was true.

Notably, Carson bequeathed $5 million to his alma mater, the University of Nebraska. In 2004, he donated $5.3 million to the school. His generosity to the University was singular and significant, creating the Johnny Carson School of Theatre and Film. Carson also seeded the John W. Carson Foundation, which donates millions of dollars, including animal conservation groups, medical causes, youth groups and education. He contributed to the Carson Regional Cancer Center, in Norfolk, Nebraska, among others.

Comments

It’s hackneyed, but true, to say there’s nobody like Carson, now. We’re too pretentious, too self-righteous and too frightened of the dark. Carson derided such attitudes and fears. He wouldn’t let the delusion consume us.

"Did ya notice," Carson might inject into a monologue, "it's the 'Tonight Show, with Jay Leno.'" In his day, it was the "Tonight Show, starring Johnny Carson." There's more prominence in the word, starring, than the word, with; maybe, when Conan O'Brien takes over, it'll be the "Tonight Show, and Conan O'Brien."

Carson knew the worth of an open-mind and subtle satire. He’d a gimlet eye for social perils. His sense of social responsibility demanded he say, “Watch out!”

Carson continued the vaudeville tradition of Steven Allen. Jack Paar used the Allen mold, but was more interested in guests than schtick. After Carson, the show veered to a convention or trade show style. The vaudeville mantel moved to David Letterman. If Conan O’Brien takes over the “Tonight Show,” in 2009, a 21st century version of the Allen, Paar and Carson style may reappear on the “Tonight Show.”

Disguised as a Midwestern good-guy, Carson promotes an eastern liberal agenda. Midwestern means everybody has a say, and you go slow. Eastern liberal means make decisions that benefit all, especially those who aren’t so well off. The combination is efficient and effective.

Dick Cavett tried for the same balance. Carson was self-effacing and a tad edge. Cavett was too often serious, even insufferable. Cavett interviews meandered, the audience rescued by a commercial break. Carson knew how to cycle the parts of a show. Cavett chased ideas, often forgetting the point, and his shows stalled. Nebraska only gets you so far.

Carson was the voice of many generations. When he arrived, boomers were coming of age. Their parents comprised the bulk of his audience. When Carson retired, children of the boomers were entering college and tuning in to him.

Success for Carson came via hard work. Holding an audience of 20 million, three nights a week, is a mighty task. Many top 10 prime time shows, today, barely reach that mark. Carson did it at 11:30 pm.

Open, honest and warm, Carson was no fool. The duplicity, which passes for much media content, now, wouldn’t have escaped his Midwestern wrath. The Chinese, supposedly, say that laughter ensures you learn well and remember. Carson surely agreed.

Carson spoke the mind of America. Everybody had the same basic set of freedoms, Carson seemed to say, the right to work, speak freely and choose. Earned differences, such as success and wealth, flow from freedom. Choose you goals, he might say, work hard and you’ll succeed. Carson led by example.

Carson ran the gamut of emotions. He laughed, easily, and cried. Often surprised, he was seldom bewildered. When a young leopard took a swat at him, he ran across the stage, jumping into the arms of Ed McMahon. The tabloids evoked his anger. He took enormous joy holding a baby gorilla or orangutan.

Monologues, shtick and interviewing came natural to Carson. Yes, as Evanier and others note, he toiled. Nonetheless, Carson seems an unusual blend of nature and nurture. Jack Benny and Fred Allen share the blend.

Carson knew how to interview, too. The art of the interview also comes naturally to Dick Cavett. Cavett, as interviewer, isn’t as disciplined or tempered. Whereas Carson moved apace, Cavett preferred to linger. No one, before, during or after the Carson era, commanded all elements as effectively as did Carson.

Cavett and Carson shared a dubious honour, in 2006. The Omaha Press Club (OPC) celebrated its 50th anniversary, with a star-studded “Face on the Barroom Floor” ceremony. Carson and Cavett were the 103rd and 104th Faces to go on the OPC floor. This was the first double-face ceremony in OPC history! Cavett spoke, and unveiled both faces (sic). In a tribute to Carson, local radio announcer, Gary Sadlemyer, of KFAB-AM, performed as “Carnac the Magnificent.” Omaha Mayor, Mike Fahey, portrayed Ed McMahon. It was surely a sight.

Carson didn’t pine for prime time, as did Allen and Paar. His audience was ten or twenty times larger than was the audience for Allen or Parr. His paydays were huge. The pressure, stress and risk of prime time offered little reward. Carson made late night respectable. As Steven Parker, “The Car Nut,” said, “Carson always seemed a bit uneasy, especially with success.” In late night, he was as comfortable as he could get.

A few comparisons are inevitable. Cavett, Letterman and Leno help expose one aspect of Carson and his work. Groucho, Jack Benny and Fred Allen are a natural fit, purposively forged by Carson. Least obvious company for Carson includes Bill Hicks and Richard Jeni.

Benny brought the class, and the timing. Groucho and Fred Allen are satirists for all time, even if Allen was too topical to escape his era, the 1930s and 1940s, intact. The influence of these satirists on Carson is clear.

Allen had a problem Carson didn’t share. As "Uncle" Jim Harkin told me, more than 40 years ago, “Allen constantly prowled for work, as he was fired [from vaudeville jobs] every few days for doing comedy that shot over the heads of the audience.” Carson often shot over the heads of viewers, but television gave him the chance to reach out and pull viewers up. Vaudeville didn’t give Fred Allen this chance, but radio did.

The Carson style was to wrap satire in bad jokes or give a sidelong glance of obvious disapproval. His message was clear, if you listened. He maintained decorum and dignity, at all times.

Some mistook the Carson satire for a chill. He certainly despised blatant deception and ideological foolishness even more. To these and similar antics, he was cold.

Hicks conveyed many of the same messages as did Carson. His style was aggressive, demanding and blunt. Carson used stealth, injecting his point before you knew it.

Jeni worked an area between Hicks and Carson. He shared their point of view, it seems. Avoiding the outright aggression of Bill Hicks, Jeni never quite managed the stealth of Carson.

Carson and Lenny Bruce had nothing in common. Bruce worked a poor me angle, well. Carson was always about us.

Carson told a biographer, Paul Cockery, “I can't say I ever wanted to become an entertainer. I already was one, sort of – around the house, at school, doing my magic tricks, throwing my voice and doing ‘Popeye’ impersonations. People thought I was funny; so I … took entertaining for granted .… It was inevitable that I'd start giving little performances.” What might Carson have said if asked about making people think?

On his final show, Carson said, “I found something that I always wanted to do.” This is a mild contradiction to what Cockery reports. His final comments didn’t convey any sense of taking anything, himself, his audience or his work, for granted. Evanier noted Carson felt everything was at stake on every show, which doesn’t support Cockery, either.

Separating Carson from other entertainers, tying him to a small, select group of ostensible comedians, is that he makes you think. Before you finish laughing, an idea takes root. Be wary of narrow-minded politicians or those who put themselves first and you somewhere down the line. Think twice about your health, and media content. Differences in success or wealth are acceptable, if you’re sure the least successful, the most needy, aren’t suffering.

In a democracy, the best anybody can do is remind us of what’s right and hope we act accordingly. Most of the time, we act on advice from significant others. Therein resides the lasting effect of John William Carson.

Sources and Notes

Some consider the Congressional Gold Medal equivalent the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Satire is used, with purpose, to describe the work Carson. Jokes amuse, and cause you to smile. Comedy rouses laughter, and, as an old-time movie, makes you feel happy. Irony reveals action worthy of ridicule. Sarcasm is the penalty hypocrites pay for their hypocrisy. Satire includes amusement, comedy, irony and sarcasm, coming together to cause change. The depth of satire ensures satirists have a lasting effect. The ideas they tender cycle through the mind, for a lifetime and across time. Satire, not satirists, last.

Peter Bart (1992), "We Hardly Knew Ye," published in Variety on 18 May 1992.

Jack Boulware, “Johnny Carson,” posted on Salon for 20 February 2001.

Tom Buckley (1989), “His Wives and Other Strangers,” is a review the Learner biography of Johnny Carson, published in the New York “Times,” on 23 July 1989.

Dick Cavett (2005), “Online NewsHour, with Jim Lehrer” transcript of “Remembrance” for 24 January 2005 is available at PBS.

Paul Cockery (1987), “Carson, the Unauthorized Biography,” published by Randt Company.

Stephen Cox (1992), “Here's Johnny!: Thirty Years of America's Favorite Late-night Entertainment,” published by Harmony.

Fred de Cordova (1988), “Johnny Came Lately: An Autobiography,” published by Simon and Schuster.

David Edelstein (2005), “Johnny Carson: the naughty genius of late night,” on Slate, 24 January 2005.

Mark Evanier (1991), “Johnny Carson,” in “Hollywood Superstars No. 3.” Article currently posted on Provon Line.

Stefan Kanfer (2001), “Groucho: the life and times of Julius Henry Marx,” published by Vintage. Pp. 359-360.

Sy Kasoff (2000), “More than Laughter: my days on the “Tonight Show, starring Johnny Carson,” published by Authorhouse.

Erik Knutzen (1992), "Celebs Say Thanks, Johnny," published in the Boston Herald on 21 May 1992.

Laurence Learner (1989), “King of the Night: the life of Johnny Carson,” is published by William Morrow & Company.

Officially, the “Tonight Show Band,” during the Allen, Paar and Carson runs, was the "NBC Orchestra.” "Doc Severinsen and the NBC Orchestra” was an alternative name for the band, from the late 1970s.

Ed McMahon (2005), “Here's Johnny! My Memories of Johnny Carson, the Tonight Show and 46 Years of Friendship,” published by Thomas Nelson andRutledge Hill Press.

Mark Rahner (200), “A former Mrs. Carson releases the classic ‘Johnny Carson Show’ on DVD,” published in the Seattle “Times” for 2 March.

Tom Shales (2005), “Johnny Carson, the Late-Night Host Whose Best Act Was Himself,” an obituary published in the Washington “Post” for 24 January 2005. P. C1.

Ronald L. Smith (1987), “Johnny Carson: an unauthorized biography,” published by St. Martin's.

Don Sweeney and Ed McMahon (2006), “Backstage at the Tonight Show,” published by Taylor Trade Publishing. “Forward” credited to Ed McMahon.

James Van Hise (1992), “40 Years at Night: The Story of the Tonight Show,” published in the Las Vegas Pioneer.

Richard Zoglin (1992), “And What A Reign It Was: In His 30 Years, Carson Was The Best," published in Time magazine for 16 March 1992.

“The Tonight Show, starring Johnny Carson” and “Johnny Carson” are available from Wikipedia and Johnny Carson On-line.

dr george pollard is a Sociometrician and Social Psychologist at Carleton University, in Ottawa, where he currently conducts research and seminars on "Media and Truth," Social Psychology of Pop Culture and Entertainment as well as umbrella repair.

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- Pitching Justinio and Jolanda

- Charitable Space Invaders

- Das Scandal

- Sjef Frenken

- Multiple Choices

- On Being Even-handed

- La Vie en Rose

- Jennifer Flaten

- Bend Over, Cough

- Catastrophe

- Baby, It's Cold Outside

- M Alan Roberts

- Thin Skin

- Passive Aggression

- Lies and Fear

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Fire Alarms

- Stop the Madness

- Just Wondering

- Streeter Click

- Why Grub Street?

- Summer & Bradley

- Social Effects of COVID

- JR Hafer

- Rosko

- The Kingston Trio

- Scott Muni

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- What Might have Been

- Coin Diving

- My Four Susans

- M Adam Roberts

- Humble Pie

- Nick the Busker

- Last Stand

- Ricardo Teixeira

- Harmony

- Monkey Business

- The Future