An Essay on Art

Melissa Yue

Introduction

Streeter Click

Art plays a central role in our social life. It's everywhere; in our homes and offices; on television and radio; in museums and galleries. Art defines and reflects our world.

We experience art. Billboards and bus boards flash past us, on the street; buy me, it urges. Architecture defines the city; Chicago is the Sears Tower. Literature shapes our ideas; a rose by any other name is still a rose.

We express importance through art; religious icons, flags of nations and product logos, and the artist, too, who says, "I am what I create." Art soothes, caressing the mind, with images, sounds or smells. The aesthetic carries meaning, balancing hope against the harsh day.

Art ensures connections across generations. Museums and galleries display the work of artists from long ago. Differences emerge through art. The early 16th century relied on religion. The early 21st century celebrates science. You see it in the paintings.

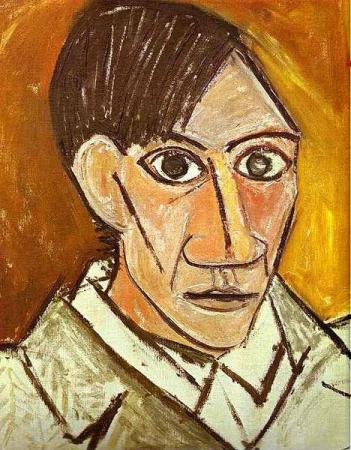

The uses of art are many. Hitler, Stalin and Mao used art for propaganda, to express cruel ideas about the world. Robert Mapplethorpe enraged conservatives, with his erotic photography. Picasso made us think and Matisse calmed us, as they earned a living.

Art is a status symbol. Owning the Blue Boy, painted by Thomas Gainsborough, about 1770, confirms your wealth and power. A limited edition print, signed by the artist, implies you are an up-and-comer. A poster, of dogs playing poker, suggests warm draught and pizza may be your idea of fine dining.

The photograph seems a modern favourite. Black and white stirs our imagination, said Marshall McLuhan, to infill the colour. We imagine colourful brushstrokes, texture in gloss.

Sculptured antlers, bones and stone, honed into the shape of a woman, may be the oldest know forms of arts. Still, the wall paintings, deep inside the Lascaux Caves, in France, get the most attention and date to 18,000 BCE. The Caves, discovered by 4 teenagers and a dog, Robot, in 1940, contain 2000 paintings, at least 900 of animals.

The cave at Arcy-Sur-Cure dates to 28,000 BCE. These paintings depict Mammoths and prehistoric rhinos. Off, away from the main paintings is one of a small hand, outline by red; a child, at play, all those eons ago.

Medieval technology focused on painting to satisfy the interests, of artist and consumer. Experiments in perspective, with inks or brushstrokes, too, created masterpieces. A closing dusk turned a widening dawn.

The status symbol held wealth. Although subject to great highs and lows, in price, masterpieces held value. Today, 25 million dollars is not an unheard-of price, for a van Gogh or a Picasso, if any ever comes to auction.

Despite recent turmoil in the financial markets, there are no signs the art market is softening. Art is hot, especially paintings. The fall 2007 auction season, in New York City, reported the Associated Press (AP), saw robust prices across most categories. Post-war and modern works lead the way. Seems a new record shattered at every art auction.

Several facts help explain the strong showing in the art market for originals. A weak US dollar and growing world wealth top the list. Less noticed, but important: new buyers from countries not known for art collecting community. Over the last five years, wealthy buyers from Russia, China, India and the Middle East have helped fuel the art market.

Prologue

Jen Gerlach

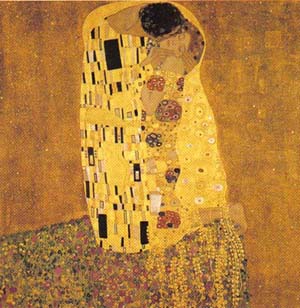

AP lumps original, with unique, in what it calls the "Art Market for Originals." A unique work of art is one of a kind. The Old Guitarist (1903) by Picasso and The Kiss (1907-1908), by Gustav Klimt, are unique. Total involvement, by the artist, defines a unique work.

An original, which need not be unique, features some artist involvement. A limited edition Klimt may be a silk screen copy, 80% the size of the unique painting. It is original, not unique. Klimt had no role in its production.

Art may be original and unique. Monet painted The Japanese Bridge twice, once before and once after cataract surgery. The paintings are strikingly different, each an original and each unique.

Most costly are unique works of art. The price of an original depends on the extent of artist involvement. More involvement, by the artist, raises the price of an original.

A few wealthy individuals and many well-funded institutions buy most, of the high end, art, today. Clear and consistent pricing lends credibility to an artist. On this point, the art market differs from no other market: buyers want straightforward pricing.

Clear, consistent pricing assigns value to works of art, such as paintings. The value reflects the category, such as Impressionism or Pop Art, and the artist, such as Manet or Warhol. The value or price depends on other works, in the category, and other works by the artist.

Similar paintings thus sell for similar prices. This is the goal clear, consistent art pricing. The artist chooses the basis for evaluating his or her work. Assessing his or her work and setting a price stems from this basis.

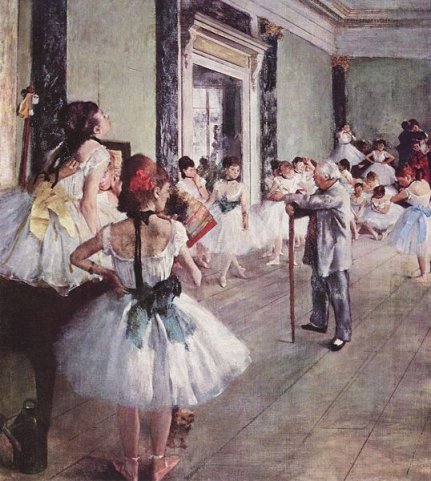

Impressionism, for example, was the first modern style of painting (above, left). A reaction to the formal, rigid and studio style, preferred by traditional institutions, such as l' Academie des Beaux-Arts, in Paris, Impressionist painters worked outside. They actively studied the effect of light on objects, preferring to paint landscapes (above, centre) and scenes from daily life. The showing, of Dejeuner sur l'herbe, by Edouard Manet, caused a scandal, in Paris, in 1863. It showed at la Salon des Refuses, founded by artists rejected by l'Academie des Beaux-Arts. The best know Impressionists include Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro and Pierre Auguste Renoir, in France, and Alfred Sisley in England. Sketches and paintings, by Impressionists, cost from $1,500 USD to several million. Usual pricing for Manet is $4,500 to $12,000, according to Sotheby's auction house. Works by Degas start at $40,000 and can cost as much as $6.7 million.

Fauvism (above, right) is another style of painting. The name, Fauvism, comes from the French word for "wild animals." This new, modern art style is abit wild. The dominant colours are strong and vivid. Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh took Impressionism to the limit, using expressive colours, but Fauvism went further. Simplified designs combined in an orgy of pure colours dominate Fauvism. The first showing, of Fauvist art, was in 1905. Among the best-known Fauve artists are Henri Matisse, Andre Derain, Maurice de Vlaminch, Kees van Dongen and Raoul Dufy. Prints and paintings, by Matisse, recently, auctioned at Christie's, range from $23,800 to $33.6 million.

Exprssionism, simply put, was a German version of Fauvism (above, left and centre). One group of Expressionists, Die Bruecke, the bridge, worked in Dresden and included Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein, Otto Mueller and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. After the First World War, Der Blaue Reiter, The Blue Rider, displaced Die Bruecke. Based in Munich, Der Blaue Reiter artists included Franz Marc, August Macke, Gabriele Münter, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Alexei Yavlensky. As recently as February 2008, originals, by Franz Marc, sold for between $1.6 million and $24.6 million, at Sotheby's.

�

�

Art Nouveau (above) or New Art, features a decorative style and dedication to natural forms. Art Nouveau was popular from 1880 to 1910, and was an International art movement. Germans called it Jugendstil. Italians called Art Nouveau, Liberty. Austrians called it Sezessionsstil. In Spain, it was Arte Joven.

Art Nouveau expanded to all forms of art, including architecture, furniture, jewellery, glass and illustration. The subway entrances, in Paris; glass work, of Emille Galle; Louis Comfort Tiffany, in the USA, and posters by Alphonse Mucha are typical examples of Art Nouveau. Gustav Klimt may be the most widely known painter, working in the Art Nouveau style. After the First World War, the style lost appeal. In part, Art Nouveau, rooted in high-quality handicrafts, couldn't meet the limited standards needed for mass production. The style was also expensive. Today, the cost of an Art Nouveau unique runs from $12,000 to $2.7 million, recently paid for The Kiss, by Gustav Klimt (above, right).

Art Deco was a design style, popular in the 1920s and 1930s. In simplified terms, the Art Deco movement follows up style on Art Nouveau. In a more simplified style, itw as open to mass production (above, right). The Art Deco movement was dominant in fashion, furniture, jewellery, textiles, architecture, commercial printmaking and interior decoration. Best-known, for working with Art Deco, especially i jewellery and glass-making, is Rene Lalique. The Chrysler Building (1930), in New York City, is an example of Art Deco style in architecture. Art Deco jewelry, such as the work of Rene Lalique, costs from $100,000 to $500,000, for glass jewelry. Pieces, which include special cut stones, cost from $200,000 to $15 million.

Work in Cubism (above), another modern art movement, mostly involves painting and sculpture, but affects all modern art. Post-Impressionist, Paul Cezanne (above, right), inspired Cubism. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braques, in Paris, before the First World War, did the earliest works. Cubism had strong roots in African tribal art. The style favours geometrical forms and splits images into parts, represented almost mathematically. Cubism suggests an inherent mathematical order. Often, several parts of one subject show simultaneously. Viewers must spend more time learning a Cubist work of art than an Expressionist work. Besides Pablo Picasso and Georges Braques, Robert Delaunay, Marcel Duchamp, Juan Gris and Lyonel Feininger are notable Cubist artist. Many Expressionist paintings, such as those by Picasso, are thought priceless. For Cubist works, available for sale, the price ranges from $25,000 to $21 million.

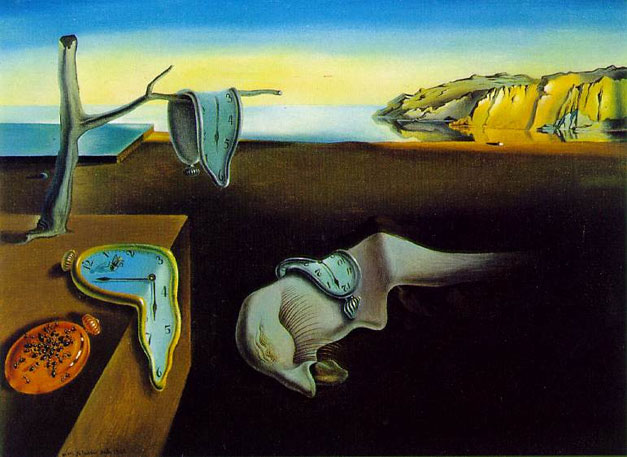

Surrealism is another modern art movement, of the 20th century. Its philosophical father is Andre Breton, a French poet and writer. He subnscious, dreams, and the social psychology of arts. Surrealism became an important movement in the fine arts, literature and in films, by Bunuel. The best-known names are Salvador Dali; Giorgio de Chirico, with his strange and eerie town views; Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Joan Miro, Yves Tanguy, Rene Margritte and Marc Chagall. Work by Chagall runs from $36,000 to $90,000, which is typical for the Surrealistic art.

Cubism (above, right) inspired Abstract Art. Russian-born painter, Wassily Kandinsky, is the father of abstract art. The Lenbachhaus Museum in Munich houses his work, which vary from semi-abstract to abstract. Piet Mondrian, a Dutch painter, is also a dominant figure in Abstract Art. Mondrian used Cubism, when he worked in Paris. During the Second World War, many leading artists emigrated from Europe to the United States, including Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp and Marc Chagall. New York City became the centre of modern art and abstract painting. Works of Abstract Art currently cost between $28,000 and $450,000.

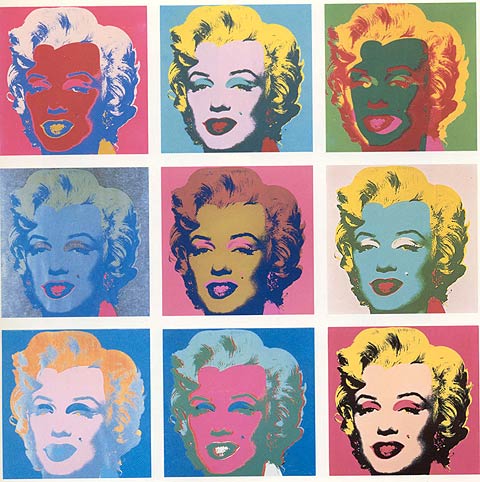

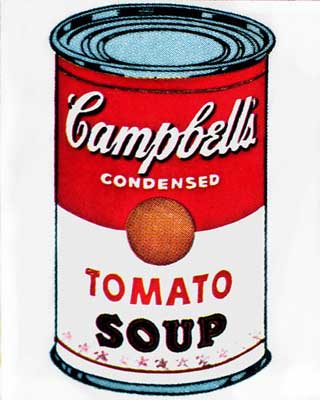

Pop Art, short for Popular Art, wanted to bring art into daily life. Pop Art reacts against abstract painting. Pop Art artists viewed abstract art as too distant, sophisticated and elite. The focus of artists, working in Pop Art, is everyday objects, such as soup cans or comic books. Typical, for Pop Art, is serigraphy (above), a photorealistic, mass production technique of printmaking. Andy Warhol (above left and centre) tried to blend fine arts and commercial arts, used serigraphy. Many album covers, of the 1960s, featured Pop Art. xxxx Mostly an American and British art movement, Jaspar Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, David Hockney, Claes Oldenburg, Roy Lichtenstein (above, right), Georg Segal, Wayne and James Rosenquist are important pop artists. An Andy Warhol original may cost from $75,000 to $190,000.

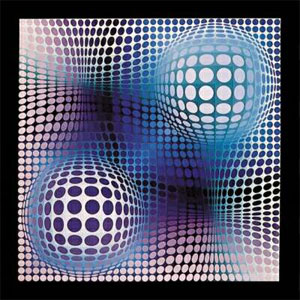

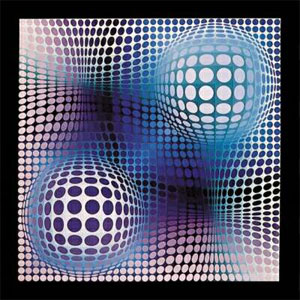

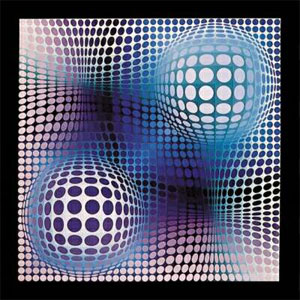

After Pop Art came Op Art (above). Short for Optical Art, Op Art used geometrical forms, as did Cubism, As well, Op Art might use black-and-white contrasts or brilliant colours; all choices are open. In the 1970s, Op Art blended into fashion design. Op Art was not as popular or mass-movement of modern art, as did Pop Art. The most prominent artist, working in Op Art, today, is the Hungarian, Vasarely. Typically, the price, of Op Art, ranges from $1,350 to $21,000.

Brushstrokes

Not everyone can or wants to pay going prices for high-end art originals or unique works. Yet, interest in art and its central role in our lives, creates a demand. The demand for decorative art is so high, for so many reasons, people hang framed pages from magazines on their walls.

Brushstrokes®, an on-line art seller, offers a solid solution for the problem.

Mitch Wine (MW) You go to a museum or art gallery. You see an original or unique you might find attractive. What you get, with an original, is that it's tactile.

GS Mitch Wine (above) is President of Brushstrokes®

MW You see the texture of the brush strokes. You see the mix of glossy and matte finishes of the paint. If you put the painting in the light, the light dances off the brushstrokes.

GS Art is something special. Art can be an emotional experience. People think less of reproductions.

MW Yes, even though the experience can be much the same, if the reproduction is created authentically. Almost no one can afford an original Degas. Anyone can afford one or more high-quality Degas reproductions.

GS Is the problem, with art reproduction, perceptions of quality?

MW All other forms of art, books or music, for example, accept reproductions. At Brushstrokes®, we managed to create quality reproductions. Our reproductions are almost as close or identical to the original, in every art form.

Think about a book. No one thinks twice about buying a paperback copy of a best-seller; it's identical with the hard cover edition or the original manuscript. What you want is the genuine experience. The paperback version provides that experience, as well as the hardback and the original manuscript.

It's the same in music. We used to have phonographs; we had 8-track tapes, cassettes and now CDs. Again, it's to get the authenticity.

GS In art, when you bought a reproduction, you used to get paper.

MW Yes; you bought a poster. The colour wasn't bad, as far as the colour re-creation goes. Still, you didn't get much quality or the three-dimensionality of the original.

If you bought paper, you then went to a frame shop. You framed the paper. Now, you had glass interfering, with the experience. When the light bounced off the glass, all you got was glass, not brushstrokes.

GS Has the art world found new ways to recreate images?

MW What happened, about 15 years ago, is printing has improved. Listen closely. Do you hear the hum, on the other side of the wall? That's our printers.

Now, art publishers use a new process called a giclée. A gicle;eis French for squirt. What happens is publishers print on canvas, not paper. A giclée is more authentic since it has canvas texture.

The problem is there's a fair bit colour loss, with a giclee.The colour of the gicle is not as good as the colour of the original or even the colour on paper reproductions. The canvas is porous. It is a substrate that soaks up the inks. The colour gets deadened a fair bit.

Canvas quality improved, with coatings. The colour recreation is improving, in many ways.

We still don't have three dimensions of the brushstrokes of an original or unique. Neither does paper. Compare that with a Brushstrokes image, which is a three-dimensional reproduction. For our higher end Brushstrokes, we have artists further enhance the image with oil paint.

The Brushstrokes image is close to the original. It's difficult to tell them apart. We have six patents on the product. We, Brushstrokes�, are the only company that can produce these images. If you talk to anybody in art reproduction, they'll speak to the quality of our reproduction process.

GS Was it you who came up with this idea?

MW No, not me, I originally had a partner, Harvey Kalef, a true gentleman. He developed the business. He was a visionary.

Kalef always wore a suit and tie. He never ate at McDonalds, in his entire life. He never wore a pair of blue jeans, either. He always had his fingernails manicured. There are not many men like him, today, or ever, I guess.

Kalef loved Impressionist art. He said, "Why is it that if I love great art, I have to settle for something really second-rate in art reproduction?" He was one of the great entrepreneurs. He put a lot on his own life into developing Brushstrokes®.

GS How did this idea come about?

MW I think it's because art touches people's emotions. People love art. Yet, art has been the almost exclusive domain of the wealthy for years.

If you can share great art, with everyone, which means you have different price points, people respond. If you look at the museum pieces, we know the Impressionists for a reason. You know a Van Gogh, you know a Renoir for a reason. Their art was incredible. People want to be able to experience it.

I have a great story. Our call centre reported someone ordered his 15th image. So I said, "You know, anyone who's ordered his 15th image, I want to call that person and thank him for supporting us." So I called him.

This man lived in San Diego. He was retired. He got on the phone, and his wife got on the phone.

They told me about all the images they bought, all museum pieces. They told which rooms, of their home, had one or more of our images. They went on and on about why and how much they loved our art.

They said, "You know last year, we were in Paris at the Muse d'Orsay and we saw Degas' "Dancers in Blue." We like yours better." I said, "Could you send me a letter, please? I would love to be able to show that to some people." I'm not sure Degas would feel the same way as he did, but it was a great experience, talking with this couple.

GS Besides hearing things like that, what else kind of makes this whole thing rewarding for you?

MW We get many letters, but that one's special. I also enjoy dealing with the artists. I had no background, in art, when I joined Brushstrokes. Since then, I've spent much time with our artists, both established and developing artists. It's just extraordinary to see the talent these people have. So that's fun.

I remember I went to my first trade show, which was in March of 2003. It was New York Art Expo. I walked in, and there was this huge room filled with unbelievable art. I called my wife, immediately, "You know, next year you're going to have to come here, with me, because this is incredible." You get to walk and talk to people about their art and whether they would consider allowing you to publish some of their art in our catalogue. Some say yes and some say no. Either way, it's a great experience.

GS Do you find that more people are buying from your catalogue or from online?

MW We have a strong catalogue following. All catalogue companies have considered whether they should scale back their catalogue. Since the Internet took off, catalogues are expensive marketing tools. I think many companies, selling a certain type of product, realized there's something about the experience of being able to feel the catalogue and read about the products at a leisurely pace. That's something you just can't match on a computer screen. We still get more business from the catalogue than we do with on-line.

GS Is the Internet a new venture for your company?

MW We've been selling via the Internet for as long as the company has been around, a little over five years.

GS What can you tell me about the people who buy these pieces?

MW Our customers skew a little older. Interesting, for a catalogue company, they don't skew as heavily female as do most catalogue shoppers. Our data suggest an even split between men and women.

What we believe based on some surveys and because our price points are a little higher, is women are more involved in picking the image and men are involved because the price is high. The wife doesn't want to make a decision without involving her husband. That's our sense of it: a joint decision.

Our customers also tend to be more affluent. Our images aren't inexpensive. Affluent, up to a point; if they're wealthy, they can buy originals. Our buyers are at a level below where people don't have all originals in their home, but they like to have art that looks like the original. That said, almost anyone can afford one or another of our products.

GS What are the lowest and highest priced items?

MW We have three collections in our catalogue. You can see them on our walls. The first collection, the Designer Collection, is our lowest-priced collection.

The thinking behind the Designer Collection is it's a decor item; it's for decorating. Someone is apt to pick these images because of the colours. It'll look good in a room in your home. So you are picking just for your kitchen or for another room. It's decor-focused, it's not art-focused. The Designer Collection price points are much lower. We have only open editions, not limited editions, in the Designer Collection. Good frames, but not the same quality of frames as we have in the other editions. The price points vary from about $300 to $600, depending on size.

The next collection, our oldest, is the Museum Collection. This company started on the Museum collection. It's just what it sounds like. It's great art by great masters from great museums around the world. It focuses on the impressionists, such as Van Gogh, Renoir and Monet. Van Gogh, Renoir and Monet are our three most popular artists by far. Then you have Pissarro, Degas and a few others who round out that group. We do well with some of the great American artists as our customer base is largely American. The prices, for the Museum Collection, range from $500 to $1,000.

Then there's our Signature Collection. This is our high-end collection. These images are from living artists, collectable artists. These artists have arrived. Their work is popular. We do limited editions, ranging from 50 to 125 copies. The artist signs every image in the Signature Collection. The frames are top quality. Prices, for the Signature Collection, start around $700 and go as high $3,500. A typical image, in this collection, costs between $700 and $1,500.

GS You said your customer base is mostly American. Have you tried to branch out more to Canadian audiences?

MW I'd like to give you a popular answer, but the truth is no. Canadians are not as open to catalogue shopping. I can't remember the number, but the average American gets about 15 catalogues a month. Canadians don't buy from catalogues, but Americans do, in large numbers. The Canadian dollar being so weak for so long didn't help, but that's no longer an issue. Combining these facts, plus two languages in Canada, compelled us to focus on the US market.

GS But hasn't having the business online opened up a lot of doors?

MW Yes; still we see few sales to Canadians. We have a currency converter, on our site. If you want to buy in Canadian dollars, that's fine. I'd guess a small percentage of our business is from Canadians. We do some business worldwide, for the same reasons. Overseas freight is pricey, too.

In the end, most of our business is from the USA. When you combine the product cost, with shipping and access to our customer service, Brushstrokes® makes sense for buyers in the USA. It would make the most sense for Canadians, but they don't buy through catalogues or on-line, as much as do Americans.

GS What do you think it would take to get more people interested in art, in general?

MW I have a personal view. I'm not sure it's correct. I think art intimidates many people.

I always think I should know more. Many of us go to galleries, to look at art. Someone comes over to help you. You are shy, and often the sales help sneer, at you, because you don't know or think so-and-so is a good artist, but the staffer expects you to know. Art can be intimidating.

We've tried, on our site and with some success, to make art comfortable. I don't think we are as successful at this as we'd like, but we are trying harder every day. At Brushstrokest™, we try to make people comfortable with art. That's why the Internet can be great: you don't have to talk to anybody. We try to show ourselves as the art authority, so people are comfortable, with our ability to recommend art.

I recently read a good article. One of the great gallery owners, in New York City, said, "Develop your eye, but buy with your heart." I thought that was good. There is something about good art and you can learn it over time, but buy with your heart.

GS What about reaching out to youth? What would you propose as a way to get youth involved in art?

MW That's a good question too. We start at a disadvantage. We are more expensive, and, as a result, buying power rules out many younger people, who are starting out.

I also think you have to grab younger buyers, with a strong present-day look. I don't see many 25-year olds buying the old masters; more trendy works, maybe. Either way, you have to adapt the collection.

We have to make it something fun and interesting. Art can be boring, especially if you don't know much about it. I tried to take an art history class, in university, and I transferred out because it was so sleepy. We must excite them.

I think the authenticity helps, too. If anyone, young or not, can own the quality of product we sell, instead of a poster, say, it's more interesting. In the end, price is likely what keeps younger buyers away.

GS Can you explain the process of how this all comes together. Do you see something you want to duplicate and then find the artist?

MW It can be a push and it can be a pull. I'm happy to say that we get calls from artists, now. Our catalogue is the dominant art catalogue in the US, for quality art. There are many companies selling more posters and lower-end art, on and off the web. If you are looking for good art, our catalogue is best. One guy I talked to in a smaller town in California said that all the artists in his town wait for the catalogue to see who's going to be in it.

The most common approach is to go to all the shows you can and subscribe to the magazines. Yesterday, I took a bunch of magazines, on the plane, with me. I found a couple of artists I thought, "Hey they're kind of interesting." I tore out the pages. I'll call them or send them an e-mail. Some show interest, and others don't. The art shows are important. Recommendations, from customers and others, are also important for finding new, exciting art.

GS Are the artists generally happy to have their art replicated?

MW Depends on the artist. Some artists are purists, who only want to produce unique or originals. There are fewer and fewer of this type, but they still exist.

I always tell purists, especially those enjoying some success, "You put your heart and soul into your work, and you create one. [Someone] who's wealthy [or investing] ... is going to buy [your work]. Your vision for this piece will be appreciated by one person and a few of his or her friends, maybe.

"If you publish, you will be able to share your vision with hundreds, maybe thousands of people. Isn't that one of the reasons why you love to paint. We are helping you get out to a wider audience."

There are commercial concerns, too. We pay royalties, which help. We pay a fair royalty, but artists don't get rich from us. Often, we don't sell enough, of one artist's work, to make a big financial difference to him or her.

We send out a few million catalogues, every year. We do a good job, I think, of talking about our artists. Buyers, in effect, decide how much an artist earns from us.

At Brushstrokes®, we believe part of our job is selling the artist as well as the art. You'll see, in the catalogue, there is a photograph of every artist. We write, a bit, about his or her background, the inspiration behind the image. If you go to our site, you'll see more.

I've told many artists, Canadian artists who are trying to break into the US, "You know, we'd be a good vehicle for you to introduce your name to the US." We are only selling one image. We only want to do one image of theirs. Remember, people have to go to the artist, personally, or go to their gallery for any images other than the images we are selling. We help you to build up your own reputation, and doesn't hurt you at all. Some artists agree, and some do not.

GS Do the artists, in your company, work here, in Richmond Hill, Ontario?

MW How we manufacture is a trade secret. I can't tell you how we do it. In a nutshell, though, once we get all the permissions, we re-create the original to create reproductions. We create one, and from that one, we create a number of reproductions. In the first one, which is created by artists, not people in suits, we have to re-create the texture, colour and authenticity of the original. Not an easy task, but doable.

When it's a present-day artist, we can often get the original into the plant. We have an artist who works from the original to create our version of it. He can compare the two, side by side. That's easier, but it's hard work.

When dealing with some of these great Museum images, you can see them on our web site, there's no chance we can get the original. In these cases, we get good photographs. There are many sources that supply good transparencies, of important art, from the original. You can get an appreciation, for the brushstrokes, in an old masterpiece, for example, from a good transparency.

We also employ artists who specialize. We have about ten artists, on-site. We have artists who specialize in other artists. We have one artist who loves Van Gogh. He's the go-to person, who works on our entire Van Gogh product. Overtime, he's developed a good eye for how Van Gogh would have done this or that image.

GS What kind of recognition do your artists receive?

MW Not much, in fact; our artists work for us, we are not promoting their work. We are promoting their work on other people's work. No, they don't get personal recognition.

Still, it's a good job for them. Like any of the arts, many talented people struggle to make a living and keep up their artistry. We help them stay in their craft and make a living. I'm not sure they go home and say, "Oh geez, I did a Pino, today, that was the height of my creativity." I don't think they would say that. They might say, "I got to paint all day doing a Pino and now when I go home I can work on my own art." So, it's a compromise, which works for all of us.

GS What are the disadvantages you've noticed about selling on-line?

MW The biggest problem selling on-line is we are selling a three-dimensional product in a two-dimensional medium. It's just as big a problem in the catalogue. Let me take that back, it's laughable almost. It's worse in a catalogue.

We try to make our images look great in the catalogue or on the web. If you could look at it, touch it, the experience is much more compelling. I think, with much creativity, you can do a lot on the Internet, to open eyes up to the faithfulness of the imagery. Still, I think it's a work in progress, and we haven't done a good a job as I'd like to do overtime.

It won't be long before the web is 3-D. This will help us and many other catalogue sellers, in a major way. For now, the 3-D is in the imagination of the buyer.

GS What are the more popular pieces that people buy?

MW Our client base skews traditional. That is, they prefer Renoir, Van Gogh,

Monet and other Impressionists. Today, traditionalists include Pino and James Coleman. I think it's because the heritage of the company is the Museum Collection.

When we try to branch out, successfully, into more modern works, we find traditional pieces still do better. When I say modern I mean, less traditional-looking work. Modern works include paintings by Ford Smith and Adamo.

Given our customer base, you have to focus. You can't just sell anything that has splotches of colour. I think our customer base is more traditional.

GS How many pieces, on average, do you sell a month?

It varies, and we don't share those numbers. We have a call centre that's hectic and, of course, we have the web. Sales are brisk, that's for sure.

GS Are there any companies that are doing the same things as you?

MW There are some successful companies; art-dot-com, is likely the most successful. There's another one called allposters-dot-com, which iss US-based and successful, but sells lower priced images.

GS How long does it take to create a Brushstrokes® painting?

MW If you work only on one, at a time, it takes five or six days. One image involves a solid week of work, at least. The most time-consuming part is creating the semi-original. This involves an artist, working by hand. As the key step, it can take a few days. Afterwards, the work is much more streamlined. It is a manufacturing process. After creating the semi-original, it's more efficient.

GS How has business been going since the business first started?

MW It's been going well. It's always a challenge. Business is tough, today, especially when you are dealing with exports to the US.

You've got to deal with a tough Canadian dollar. When I started in this business, the US dollar was $1.35 Canadian. A dollar of revenue, from the USA, was $1.35 Canadian; a dollar was a dollar, when a Canadian bought a painting. We lost 35 per cent of our margin when the dollar hit par. Thirty-five cents on the base of $1.35 is maybe 25 per cent. It's been tough.

Still, it's a fun business to work in. You said it when you walked into the room; it's a creative space to work. Plus, the letters I get are often wonderful. I like it. I enjoy coming to work.

GS You said that you took an art history course in university. When was it that you started to suddenly get more interested in art?

MW I wish I could give you a great story. This was a business decision for me. The man, who developed the process, needed new capital. This was in late 2002-2003. We looked at the business, and decided it was an interesting investment. I really got involved, with Brushstrokes™ because I thought it was good business. It could have been anything; pots and pans or anything. Then it got to me, it got under my skin. My original idea was to stay involved, for a bit; then leave to do something else. I grew to love this business. I ended up staying and loving it.

GS In your opinion, what does art add to the world?

MW I'm not sure a painting is any different from great music or great writing or anything. There's something about humans. We need to have our emotions challenged and soothed. I think great art does that. It's a hard world, and I'm not sure it's getting any easier. I have an image both in my office and home, which is in our catalogue and on the web. If I'm having a bad day, I turn around and look at it. Someone painted it in Algonquin Park. I think it's peaceful. I like the solitude of it. That's what I think great art does for people.

GS Is this the only Brushstrokes® painting that you have at your house?

MW No, my whole house is Brushstrokes™.

GS And how many would you say you have?

MW Twenty-five or more; it is how I came to buy the business. The story is I started to do work, in this business, with the prior owner, in the fall of 2002. That arrangement wasn't going anywhere.

I said to the guy, "You know, I'd like to buy one of your images for my home. Can I do that?" The name of the image is, "Valley of Light." It's somewhere in our offices, here, and still in my home, in the same place I hung it that first day.

"Valley of Light," when you walk into my home, it's right there. I couldn't get over how people would react when they came to my house. No one would say, "Oh, is that an original? They would say, 'Who's the artist? How much did it cost?" All the questions that suggest that obviously they think it's an original.

When I hear that comment a few times and I start to think, "There's something to this." That was the first Brushstrokes™ image I had in my home. My home is a library. I've discovered I'm allowed to bring them back. I take it home, for a while, and when we tire of one or want to change, I bring it back and take another one. There are a few my wife has been bugging me about and I still haven't taken them home.

GS Have you thought about branching out, into other kinds of art such as replica sculptures?

MW Also a good question. We sold sculptures. Not ours, but we developed a deal with a group in Spain that sells sculptures. I think we did all right, but people know us for art. I'd never want to present ourselves as something that we are not.

Portraits are how we branch out. We started selling portraits about two years ago. You send us a photograph and we turn it into an oil painting for you. On the web site, you can see the photographs sent and the portraits we did. It's going well. The emotion, again, is powerful.

The portrait business is taking off. It's fun for us. That is where we've been branching out.

GS How much do the portraits cost?

MW They range in cost, but they'd be anywhere from $300-$400 for the smaller sizes.

GS Have you tried branching out in other ways?

MW Yes; the other way we've been trying to market it, is to say to people, "Be your own artist." We do well, with paintings from Venice. I don't know why, but we put a painting from Venice in our catalogue, it just sells.

The best conclusion we have is that people love Venice. Many people have had wonderful holidays in Venice, maybe romantic holidays in Venice. This brings back memories so they buy the painting.

All right, but you are buying someone else's interpretation of Venice. Why don't you do a painting of your own interpretation, of Venice? You took a beautiful shot on your honeymoon. We'll turn that into a painting for you. Now, on your living room, instead of having James Coleman's view of Venice, which was in one of our catalogues, we'll have Mitch's view of Venice. I think there are some legs to that. We'll start marketing more strongly, soon.

GS What do you hope for the future of this company?

MW What I'd like is we continue the mission to make great art available to everyone, at an affordable price. That's not only North America. I'd like to focus, over the next few years, on taking the business to Europe and Asia. Doing what we've started here, in Canada. We certainly haven't finished the job here, and there's much opportunity in the USA and Canada. It's a tough economy, right now. Our catalogue business is hurt by the recession in the US, and why not? Many people are worried about keeping their homes. They're not worried about what art is going to go on the walls of those homes. The goal, of course, is to ride out the recession. We will, and we will continue to grow the business and bring great art to people.

GS Thanks, Mitch.

The Miami International Institute of Art and Design could help you understand art better.

Click here for a list of all Grub Street Interviews.

Interview edited and condensed for publication.

Melissa Yue is a former reporter for Reuters. She lives in Toronto.

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- Night Czar Fever

- A Zinger from Singer

- Hockey Poetry

- Sjef Frenken

- Democracy Covered

- A Petard Among Friends

- Of Exes and Owes

- Jennifer Flaten

- Tornado Drill

- Easter Peeps

- Baby Drive My Car

- M Alan Roberts

- Total Devistation

- Culture Salad

- My Bitter Half

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Sklar Rocked America

- Gas vs EV

- Reading

- Streeter Click

- Larry Glick: Cop+Creature

- Dick Summer Top 40

- WBZ AM 22 May 74

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- Pandemonium in Boston

- Gone Too Soon

- A Walk

- Jane Doe

- Vintage Radios

- By the Way

- A Quality Guitar

- M Adam Roberts

- Lazy Bones

- Can You Hear Me Now

- I Owe You

- Ricardo Teixeira

- The Future

- There is a Light

- The Unicorn