Ginormous

David Simmonds

I clipped an article from the New York Times, a few weeks ago, because it staggered me. Scientists in San Francisco developed a prosthetic voice or virtual vocal tract, with the potential to enable people that cannot speak to speak. All a patient must do is this: think of what he or she wants to say and the prosthetic voice does the rest.

Thought is action.

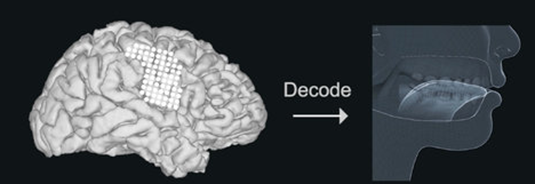

The research that prompted this breakthrough, also from San Francisco, found there are differences in the brain regions that produce the sound of speech and the areas that control vocal movements. This study focussed on the latter. The study built on recreating the sound from the movement.

The prosthetic voice test used five epilepsy patients, chosen because they had already had electrodes implanted in their brains in preparation for neurosurgery to control seizures. The control group retained the ability to speak. The patients recited hundreds of sentences for the scientists, who recorded them and watched how neuronal patterns in the motor cortex matched movement in the tongue, lips and larynx.

The researchers then used the principles of linguistics to reverse engineer vocal tract movements to produce those sounds, such as pressing the lips together here, tightening vocal cords, shifting the tip of the tongue to the roof of the mouth and then relaxing it. A decoder analysed the detailed mapping of movement-to-sound; it transformed brain activity patterns produced during speech into movements of the virtual vocal tract. A synthesizer converted these vocal tract movements to synthetic approximations of the voices of the study participants.

Study subjects then just had to think what they wanted to say, in much the same way as a Segue rider only needs to think of turning left for it to happen. The result was remarkable. Slurred, but nonetheless recognizable speech at a natural pace, of up to 150 words a minute.

Previously, some people, with severe speech disabilities, learned to spell out their thoughts letter-by-letter using assistive devices that track very small eye or facial muscle movements; think of Stephen Hawking. Producing text or synthesized speech with such devices is slow, typically about ten-words-a-minute. The new system is a significant improvement.

Ginormous implications.

Presumably, the need to pre-capture vocal patterns from patients will evaporate as a bigger speech database is generated and the algorithms set smarter; meaning in turn that is can help; people who have already lost their voices as well as people in danger of losing them. A wide group of conditions stand to benefit from this development: stroke, traumatic brain injury and neurodegenerative illnesses such as such as Parkinson’s, MS and ALS are the examples cited by the researchers.

That is fine, as we are talking about the ability to assist a person, otherwise trapped-in their bodies, to speak. There are also technologies under development that will extract my thoughts from me even though I would prefer to keep them private. This I don’t like so much.

There are products available that can determine, with a confirmed accuracy, levels much higher than human judgment; sixty-to-seventy-five per cent accuracy compared with fifty-four to sixty per cent for human judgment. For example, am I lying may be determined based on the contortion of my facial muscles or the movement of my eyes, which it already is, just not with sufficient accuracy. Although the immediate and obvious uses in the courtroom, such technologies are useful in such fields as border security and job interviews. Just think if someone were to be able to coerce me into having electrodes strapped to my brain: my thoughts would feed directly into a machine that could almost unerringly divine my truthfulness or untruthfulness in no time flat.

Once a product can tell if I am lying or not, it is only a hop, skip and jump away from it determining just what I am thinking. This may be awkward, if I am being outwardly polite to someone, but keeping my inward sour thoughts about him or her to myself.

If I can’t take any consolation from the privacy of my thoughts, what substantive privacy do I have any more? I might as well just learn to accept my inner and outer thoughts must merge, which would be a shame, as I would never be able to engage with people I don’t like. Much to my chagrin, I might discover many more people that don’t like me than I thought.

Always be wary.

Let’s toast scientific innovation. Yet, we must keep the proviso that the risks always need monitoring, closely. Those are my extracted thoughts, I promise.

Some readers seem intent on nullifying the authority of David Simmonds. The critics are so intense; Simmonds is cast as more scoundrel than scamp. He is, in fact, a Canadian writer of much wit and wisdom. Simmonds writes strong prose, not infrequently laced with savage humour. He dissects, in a cheeky way, what some think sacrosanct. His wit refuses to allow the absurdities of life to move along, nicely, without comment. What Simmonds writes frightens some readers. He doesn't court the ineffectual. Those he scares off are the same ones that will not understand his writing. Satire is not for sissies. The wit of David Simmonds skewers societal vanities, the self-important and their follies as well as the madness of tyrants. He never targets the outcasts or the marginalised; when he goes for a jugular, its blood is blue. David Simmonds, by nurture, is a lawyer. By nature, he is a perceptive writer, with a gimlet eye, a superb folk singer, lyricist and composer. He believes quirkiness is universal; this is his focus and the base of his creativity. "If my humour hurts," says Simmonds,"it's after the stiletto comes out." He's an urban satirist on par with Pete Hamill and Mike Barnacle; the late Jimmy Breslin and Mike Rokyo and, increasingly, Dorothy Parker. He writes from and often about the village of Wellington, Ontario. Simmonds also writes for the Wellington "Times," in Wellington, Ontario.

- A Puffed Up Problem

- The Bagpipe Incident

- While You Can

- High-tech Hub

- The Unknown Saviour

- An Ideal Community

- The New Rock Stars

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- No Kornacki Gnome

- Heavy on the Fluff

- Stompin' Tom

- Sjef Frenken

- Modes of Transportation

- La Vie en Rose

- Point of Entry

- Jennifer Flaten

- World Gone Mad

- Hoover Heaven +1

- Little Elvises

- M Alan Roberts

- A Loveless Life

- I'm on Fire

- Self Rules Love

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- WABC-AM Sold

- Middle Class Screwing

- Birthday 2012

- Streeter Click

- Dr Michael Sandal

- Support Us

- WBZ AM 22 May 74

- JR Hafer

- Rosko

- Tell Me All About You

- Why and Wherefore

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- Fun at Lake Eola

- Winnowing

- Rock Springs

- Jane Doe

- Watchman

- Guitar Woods

- US Debate 1 2016

- M Adam Roberts

- Lazy Bones

- My Eraser

- No Quitter

- Ricardo Teixeira

- The Unicorn

- Harmony

- There is a Light