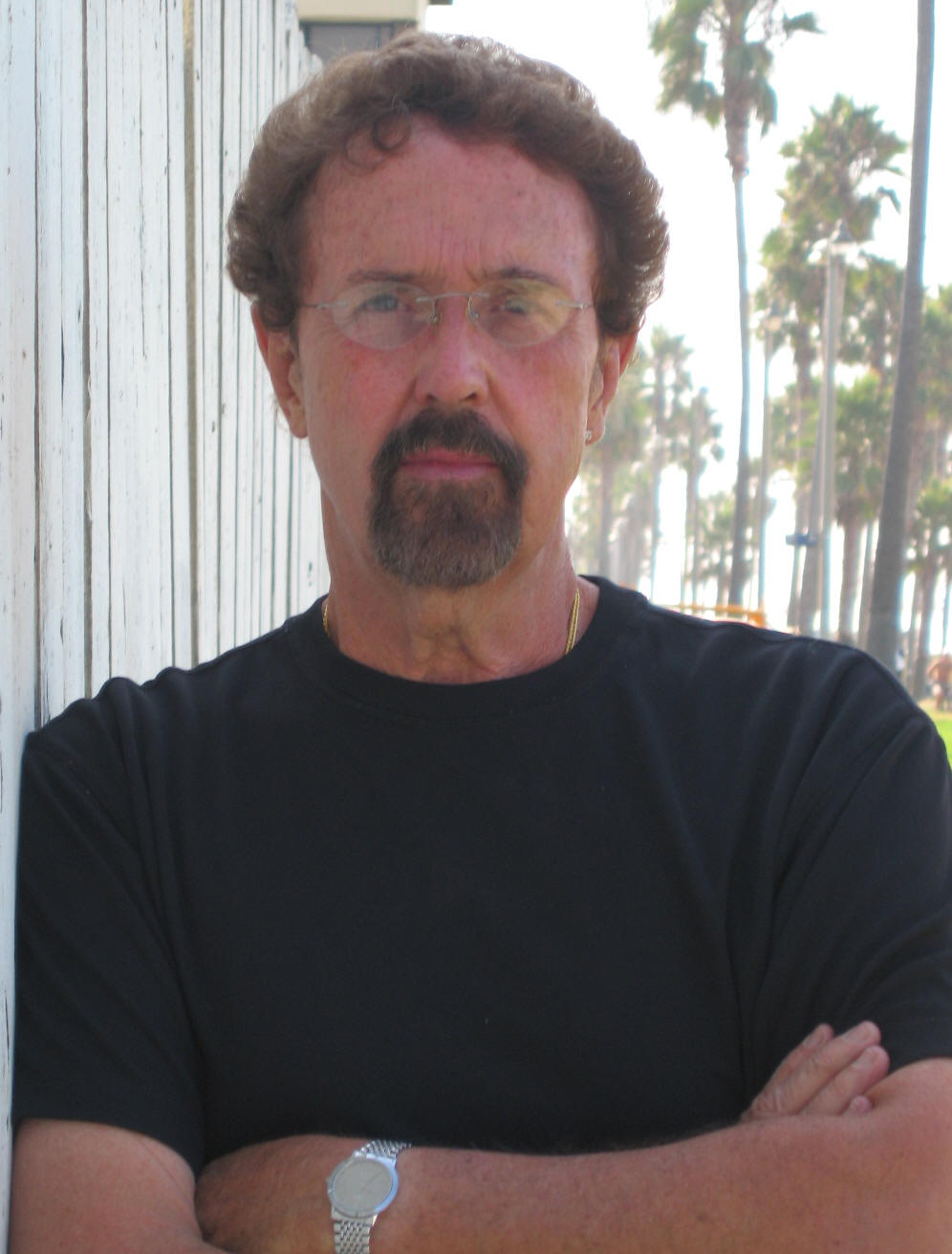

Timothy Hallinan

Rich Knight

Introduction

Shadoe Stevens*

Timothy Hallinan is simply the smartest, most creative person I know and the most inspiring. When we met, we became instant friends. Tim has been one of my best friends, all my adult life.

I met Tim, in 1970. I came to Los Angeles to work KHJ-AM and Tim was doing station promotion. He came up with some of the most innovative, creative campaigns Bill Drake and RKO General, which owned KHJ-AM, delivered. We met when Tim took some head shots, of me, for station promotions.

A year or two later, we were neighbours in Topanga Canyon. I was creating the “World Famous” KROQ-FM and Tim had formed Stone Hallinan Consulting. Stone Hallinan was an international public relations (PR) firm, with offices in LA, New York City and London, England.

Despite his success in PR, all Tim wanted to do was to write. He wrote and wrote. Every novel he’s written has received critical acclaim.

About his new novel, “Breathing Water,” Maddy van Hertbruggen writes, it’s “truly an excellent book – I don't know how Hallinan can get any better – he set the bar … high for himself! Hallinan sprinkles perfectly wrought phrases throughout the narrative, like gems falling on to the pages, never failing to delight. In some ways, it's harder to write a review for a book you love …. The tendency is to want to put out all sorts of superlatives, to gush with adjectives. Please indulge me for a moment: the book is extraordinary, magnificent, exceptional, heart shaking, heart breaking, brilliant. As I read this book, I laughed, I cried, I gasped, but I never … yawned. “Breathing Water” is a great book. Period" (from ReviewingTheEvidence.com, August 2009).

“Breathing Water” is the latest book in the Bangkok Series. This may be the only thriller series, in the world, in which the hero is a family. The family includes Poke Rafferty, an American writer living in Bangkok; his wife, Rose, a former bar worker, and Miaow, the ten-year-old street child they adopted.

At the core of these books by Tim Hallinan, there’s the love and tenderness of a family trying to stay together, while separated by culture, language, religion and, often, hair-raising events born out of real-life. Tim writes multilayered stories. His stories are rich, with colours, engaging, unforgettable characters and love. The love is of the family, of life and of the Thai people.

His mysteries are compelling and unpredictable. A novel by Tim is hard to put down. As thrillers, his books are riveting. At the same time, Tim writes with incredible wit and unexpected, laugh-out-loud humour.

I recommend "Breathing Water." After reading it, I'm sure you'll rush out to pick up the other novels in Bangkok Series. I'm certain you'll find them so rewarding, you'll forage used books stores for the six novels in his Simeon Grist Series, too.

There's no one like Tim Hallinan. He's one of the finest writers, of our time, and among the best storytellers. Read this exclusive interview, with Tim Hallinan, to find out why.

GrubStreet (GS) Thanks for giving us your time. I know you’re busy, getting ready to go back to Thailand.

Timothy Hallinan (TH) I’m ready to leave, but I started writing a piece for “Blog Cabin.” I’m also doing about twenty guest blogs for other sites. Nothing is harder than thinking of twenty subjects that have something to do with your book.

GS What do you write for these blogs?

TH To answer that, I need to take half a step back. The Bangkok Series is my second series. My first series, starting in 1989, was about Simeon Grist, a private investigator, in Los Angeles. What I liked about Grist was the books had no sequence. You could read the last one, after the middle one and before the first, without losing anything.

I imagined the Bangkok Series the same way, but I made a massive mistake. A child, a former street urchin, Miaow, is a continuing character, in the Bangkok Series. Miaow grows up, changing faster than do the adults.

You can’t read the Bangkok Series out of order. Miaow is eight years old, in “A Nail Through the Heart,” ten in “Breathing Water” and so forth. A random reading order doesn’t work for the Bangkok Series.

That’s some of what I’m writing about for “Blog Cabin.”

GS There are three books, so far, in the Bangkok Series. “A Nail Through the Heart” and “The Fourth Watcher” are out. “Breathing Water” released the other day. I read you have a fourth book in the works.

TH Yes, I’m about 45,000 words into the fourth book, “The Rock,” in that series. This is the point where I wonder why I’m writing another book. It happens to me every single book.

GS A crisis of confidence is common among creative talent.

TH I wonder why I think I can do creative writing, for a living. Is this arrogance? I’m in despair when I hit 45,000 or 50,000 words. This is true for every single book I write.

GS Why do you think your confidence wanes at this point?

TH It has to do with the way I work. I’m a seat of the pants writer. I get an idea and go.

GS The Raymond Chandler style; sit down and start. Dashiell Hammett blocked out his stories, meticulously, before he wrote, as does Robert B. Parker, today. What was the idea that ignited the book you’re writing now, “The Rock”?

For this book, the basic idea focuses on Rose and her past, her days working the bar. A nightmare character from her past suddenly shows up. The reader learns he existed. Earlier books left open the question of his existence.

Rose believed she killed him. She had many good reasons to kill him. She tried to kill him.

The return, of this nightmare character, puts the family in physical danger. It also creates stress, in her marriage to Poke. Phillip “Poke” Rafferty, the main recurring adult character and her husband, didn’t know about this part of her past.

Miaow is now 11-years old, in the next book, and desperately trying to fit in at school. Her school is full of middle-class children, whereas she’s a small, a tiny, former Bangkok street urchin. What Miaow doesn’t want is for her classmates to find out her mother was a prostitute.

The stress, of the returning nightmare character, threatens everyone. The fault lines, in the family, come out in sharp relief. In fact, I think, at this point, the family may break apart, in the next book, but not in the “The Rock,” which is the book I'm working on now.

GS You write thrillers that are as much about the family as adventure.

TH Yes, I wanted to write thrillers. More and more, I discovered my interest in families. The adventure runs alongside the passages the family goes through, rather than the other way around.

I want to explore the family. The family, in the Bangkok Series, desperately loves one another, but faces huge gulfs, in life stories, expectations, religion and culture. Rafferty is an American. Rose is a former bar-worker, in Patpong, the main red-light district of Bangkok. Miaow was a street urchin. They must work hard at forming a unit, under normal circumstances, and the adventures add to their difficulties.

Suddenly, a danger confronts the family. The danger, a nightmare from the past, say, threatens each family member differently. Still, the family, as a whole, strives to cling together. So far, it has stayed together.

In the next book, “The Rock,” Rose feels shame about her past. She knows her past might affect her marriage to Rafferty. Rafferty feels jealousy and begins to wonder to what else he doesn’t know about her. Miaow is deeply upset because the new threat goes right to the part of her life she most wants to put behind her.

That’s how I start. There’s potential for family and adventure plots and sub-plots. Still, my starting point, for “The Rock,” is Rose confronting the return of a nightmare from her past.

GS How does a book fill out for you?

TH The entire plot, all the subcharacters and everything else comes to me as I write. I don’t outline. I don’t have any clear sense of how the book finishes, when I start.

GS Your style is an adventure.

TH Yes, I let the characters, take me through the story. When I start, there are characters, who I know, such as Rafferty, Rose and Miaow. Other characters, who I don’t know, when I start, join along the way.

Someone said, fiction is telling ourselves stories and this is how I work. When I start, I don’t want to know the ending. I want to enjoy the story, its twists and turns.

GS The Raymond Chandler approach.

TH This style makes the beginning easy. All I need write is, “Once upon a time, in a country full of rocks, there lived the princess who had hemophilia and couldn’t touch any rocks.” From there, I go anywhere.

By 50,000 words, the possibilities narrow. When I’m at the middle, which is where I am, with the next book, in the series, I realize I have no outline or no idea of where I’m heading. I start to wonder how I got this far.

GS On your blog, “Blog Cabin,” you mention Charles Dickens wrote this way, too.

TH Yes, Dickens did it in a much more dangerous way than do I. He published as he went along, every month, say. I can go back to change whatever I wish. Dickens had to endure his first 5000 words when he was at 220,000 words.

I don’t know how he did it. What a scary thought, but Dickens wasn’t alone. Anthony Trollope, my favourite 19th century writer, William Makepeace Thackeray, George Elliot (pseudonym of Mary Ann Evans) and other Victorian Era writers serialized their novels. There were eight or nine magazines, which ran a chapter a month, say, and published the completed work as a book.

GS Paper was expensive, then, and serializing was good hedge against a novel that might not sell.

TH That was the publishing model in those days. They learned to prosper from it.

GS Serialization suggests a writer knows where she or he is going, from the outset. Otherwise, a mess seems almost certain.

TH Using notes, stringing out plot lines and character development was likely more common than we want to believe. We’re sure Dickens was a pantser, that is, he told himself stories, which played out by the seat of his pants. When he passed away, he hadn’t completed “The Mystery of Edwin Drood” and nothing existed to hint at where he was going with the story.

GS Hammett is a documented stringer. Chandler is a documented pantser. Is one style better?

TH There’s always been a division between people who outline and people who write by the seat of their pants. I think, on the most basic level, it’s a personal matter. Are you more interested in the story or are you more interested in the characters?

If you’re more interested in the story, I think you’re likely to be a stringer, a writer who prepares an outline before starting, approaching characters through the story. If you’re more interested in the characters, you write the characters and you let them give you the story. This is the only way I can write. I can’t outline.

GS If you don’t like stringing, how do you pitch publishers or get a publisher interested in your work?

TH When I sign a book contract, I give the publisher an outline of the novel. I create fluff I think sounds exciting and add a catchall sentence, such as “and questions arise about the motives of ….” A smokescreen ends the outline; for example, “The realization even love can’t hold back the darkness,” or some generic movie trailer language, which the lawyers gush over.

My editors understand what I do is make the lawyers happy. Editors know I’ll never look at the outline, again. I never do.

GS That’s funny.

TH Yes, it’s funny. The fluff, on the outline, lingers in my consciousness. If you’ve done a quasi-outline, on the first third of the book, even though you’re not following that outline, it lingers. The fluff always lurks, in your mind.

The outline is like a hopscotch pattern, chalked on the sidewalk and then erased. You always know when you’ve stepped outside it. Any outline is a pain, but you must do it, to some extent.

That’s how book publishing works, today. If I surveyed my novelist friends, I guess 75% work the way I do; the rest outline. If you were to do a survey of screenwriters, I think you’d find 100% of them outline.

GS Have you ever started a novel and changed your ideas or the plot line?

TH Yes, many times, anyone who writes, the way I write, continually gets new ideas. I’m always tempted to follow fresh, new ideas. Sometimes, the ideas, which originally set my imagination in motion, grow old, fast.

I had to learn to deny this temptation, every time it appeared. Two types of ideas appear. Interesting ideas are sometimes attractive because of newness. Other ideas improve what I’m writing; make it fresher, for example.

A fresh idea might appear because I’m tired of the ideas I’m working. A fresh idea might offer a new and better direction for my writing. I had to learn to recognize the difference.

GS How do you tell the difference?

TH It’s hard because I have to be open to creativity, even when it presents itself as a challenge. Sometimes, in the middle of writing a book, a challenge presents to a basic or central idea. How do I get Rafferty out of this jam?

Right now, I’m writing a scene, for “The Rock,” which I realized, a couple of days ago, has an enormous difficulties tied to it. From this realization came a different way to handle the scene. The new approach, to this scene, changes the next 30 or 40 pages, of the book.

I’m not a hundred per cent certain these changes are right. I don’t know if the changes work. What I’m going to do is write it and see where it takes me.

If I don’t like where it takes me, there are other choices. I might drop the scene or back up and find a different way to cure the problem. This is a chase scene, I’m writing, maybe one character is too smart to chase the other into an unknown area.

Still, I have to engineer a physical conflict between these two characters. The solution, to this problem, I think, is a new character that appeared in front of me; she may be the solution.

GS She, the new character, appeared and solved your problem.

TH Yes, and if she’s not the solution, I’ll back up and figure out what else to do. You caught me at a point, in the writing of this particular book, where I’m open to anything.

If someone said, “You know, maybe what you ought to do is have the Log Cabin Republicans arrive, en mass, in Bangkok. They’re after somebody who’s outing political figures via the web. They ask one of my characters for help.”

I’d say, “That sounds interesting.” Let me give it a go. It wouldn’t work, but might lead to something better.

Therefore, I’m just at a bad point, with the new book. I’ll remain at a bad point until the story starts to move on its own. If I try pushing the story, it won’t move.

GS You can always write yourself out of such holes.

TH Years ago, a journalist asked a famous writer, “Doesn’t [writing] get easier after 5-to-8 novels?” His answer was priceless, No, because I get harder to please.” The more your write, the more difficult writing becomes.

GS That’s a wonderful problem.

TH Yes, the more you write, the harder it is to write, which is the bad news. The good news is you know, in your soul, you have what it takes to finish a book. This is the big question until you finish a book.

GS Seems you plunge ahead, into the great wide open, no matter what confronts you. Why do you think so many writers can’t finish a book?

TH The big problem, as a culture, is we don’t like delayed satisfaction. If there’s a creative impulse, certain to involve delayed satisfaction, it’s writing a novel. A novel it takes a year or more to write. Maybe you can get away with it in eight months, but that’s still a long-time. Then there’s another six months to two years to publish.

By comparison, one of my siblings is a successful painter; in three or four days, he finishes an important painting. My other sibling is an illustrator, of books for children; his projects are two or three weeks long. I take a year or more, to complete a novel, after I write the first sentence. A novel is a major investment and takes up to two years to see the light of day.

Finishing a novel thus calls for dedication, which is difficult to preserve. A daily commitment to writing is necessary. A serious writer needs to write every day or at least five days a week.

If this commitment to creativity doesn’t exist, you can’t get up to speed. Once up to speed, you can keep the energy going for the time it takes to complete a novel. Many people think you can write a novel in your spare time; maybe one day out of four or five days, but few finish that way, it just doesn’t work.

GS I have a friend who published a new book every year or so. At the time, he had a senior administrative job in a comprehensive research university. He got up at 5 am, seven days a week, wrote for three hours and went to work.

TH Yes, to finish any book, you must work it every single day and realize it’s going to take a long-time. You have to keep the world, of the book, open all the time. The only way to do that is to visit it often.

Writing isn’t a digital switch. You can’t just turn it off and on. The more you write, the better you write, usually. The more familiar you become with the landscape you’re creating, the more comfortable you are living in it and so forth.

GS Can you talk, a bit, about how the writing differs from editing.

TH Writing is managing my daydream for a year. Herding my daydream, ensuring it has a good beginning, a compelling middle and an ending, which makes sense. By making sense, I mean the ending is someway consistent with the beginning and I’m happy, with what happens to the characters.

Editing is looking at how you’ve done what you’ve done. Could you make the word pictures more vivid? Does this little arc of action take too long to finish? How long has it been since a man came through the door, with a gun in his hand?

GS Yes, in case of doubt have a man come through the door, with a gun in his hand. That’s Chandler.

TH Yes, it was Raymond Chandler, who wrote excellent crime noir. He said, “When in doubt have a man come through the door, with a gun in his hand.” He was joking and he wasn’t. It’s important to make the reader sit up straight, but not too often.

GS Joke or not, it worked, all the time, for Chandler.

TH Editing is an emotionless study, of writing. When I rewrite, I go back into my daydream. When I edit, I stay outside my daydream.

When I rewrite, I’m improving on material that is already there. When I edit, the pages come to me filled, with ink or pixels. When I write, there’s nothing except the white of the page.

GS Writing or editing, do you prefer one or the other.

TH William Faulkner, the American writer, said he wrote drunk and edited during a hangover. It’s important, I think, not to allow your inner critics too much sway, when you’re writing. Inner critics whisper, in your ear, “That’s not good. You can’t do this. Why do you do think you can write a novel? Oh my god, look at that sentence. Look, you didn’t even put a comma where it belongs.”

Inner critics are likely the reason Faulkner wrote only when drunk and Chandler, too. Ignore inner critics while you write, but maybe not when you edit. I say write hot and edit cold.

Pour out creatively, without questioning your words. Question your writing when you rewrite and edit. Otherwise, the risks are high that you’ll second-guess yourself out of a book.

GS You focus on time and place. Some writers prefer editing, as it means the hardest work is behind them. Others hate editing. Some enjoy writing, where all their creative energy releases. Which do your prefer?

TH I enjoy writing. I enjoy editing. I like it all. I hate it all.

Halfway through my next book, I hate writing. It’s too hard. It feels like I’m paving a road. I don’t sense I’m building anything. It feels like I’m pressing my ideas flat, trying to make everything fit.

What I learned, from writing a dozen novels, is it doesn’t make any difference what I think as I write. I won’t know if my writing is good or not for weeks, when I read it. When it comes to the editing, I hate cutting the pieces; cutting to bits, what I worked so hard to create. Yet, I love it when some elegant, simplifying solution suddenly presents itself for something overwritten. I usually overwrite.

GS Most of us do.

TH Editing is partly an act of sanity. The first draft, of a novel, intended to run about 90,000 comes in at 140,000 words. In such cases, which are many, I need to edit.

Nor do I need five lines to write the sky is grey. In “A Nail Through the Heart,” when Miaow runs away, I wanted to describe a grey sky that makes the trees seem electric green. I wrote graphs and graphs, then one line, “A slight, light grey sky, a sky low enough to scrape a fingernail on it” was all it took. This editing I enjoy.

GS The “AT Series” is a prominent part of “A Nail Through the Heart.” Can you talk a bit about how you came across such infamy and how you work it into the story?

TH The “AT Series” is an honestly vile strain of child pornography. It’s sadomasochism, with children. The criminal, who shot these videos, is a paedophile.

The “AT Series” filmed in the old days, when there was more child sex available in Bangkok. Child sex is almost gone from Bangkok. There was a community of full-time residents and regular tourists, all paedophiles. They lived in Bangkok or came on vacation for the child sex. Now, they either are not as active or are so deep underground, no one can find them.

I knew about the “AT Series,” but figured it was a rumour or legend. Then I found it on-line. My hair stood on end, when I saw the vileness of the videos.

Still, I needed an evil identity for a central character, in “A Nail ….” The character is dead before the story begins. The reader has to hate this character, without meeting him.

I knew this fact before I started to write. His vileness couldn’t emerge in scenes, with other characters. I needed a timeless way to show his evil.

I looked for the most atrocious character I could find. If the character sold home siding, he was far less intriguing than was the creator of the “AT Series.” From this discovery came the most important character in the book, “Donught.”

Donught is a young woman. “A Nail …” is about her avenging what she suffered at the hands of paedophiles, in Bangkok. The villain came first. Then I stumbled on the idea about the murderer.

When I began “A Nail …,” I wanted to flip a convention upside-down. I wanted the murdered people to be guilty and the murderers to be innocents. This meant the crimes had to be so terrible that killing those who committed these crimes was easy to justify.

“A Nail …” is about how the guilty are innocent and the innocent are guilty. I needed horrific crimes to make the point. The “AT Series” was the most horrific crime I found.

GS It’s interesting Donught went free, after the killings.

TH In part, “A Nail …” is about acculturation of an American expatriate, into Thai society. Sometimes the extremes, of good and bad, are obvious, but most often the grey areas dominate. When is it all right to overlook a murder, of anyone, regardless how odious their abuses.

GS In the west, we find any murder hard to overlook.

TH We delude ourselves that morality is black-and-white. It’s not. Morality is grey when you don’t have enough to eat or the best housing you have is a tin shack.

Morality is grey when someone sets fire to your tin shack to replace it with a skyscraper. Morality is a more intense grey in extreme circumstances than it is in the little white picket fence town, which is the Hollywood background for America. We live well, in the West; belief in a non-existent black-and-white morality is one our luxuries.

GS Poke Rafferty, the central character in the Bangkok Series, is a farang, a foreigner living in Thailand. Do you see yourself, as a farang, in Thailand and Cambodia?

TH Yes, exactly the way it reads in “A Nail ….” Poke talks about having been to many places and entering other cultures. Yet, he saw other cultures through a pane of glass, as a display in a store window. Now, his life depends on getting to the other side of the glass.

I don’t kid myself. I don’t believe Im on the other side of the glass, in Thailand. I think I know much more about Thailand than a tourist or someone who believes what they see and doesn’t realize it’s a show for tourists.

Tourists notice the accent, the smoke and the mirrors, not the facts of Thai life. I think many people, when theyre travelling anywhere new, not only to Thailand, think, “Oh, isn’t this quaint?” There’s nothing quaint about another culture. That’s daily life for many women and men: exploitation, hardship, brutality.

Understanding daily life, in other places, is the goal of travelling. Tourists don’t make much effort trying to get on the other side of the glass; they enjoy the delusion. Travellers, as opposed to tourists, try to make it through the glass.

I aware I’m an outsider in Bangkok and Cambodia. The residents, of both countries, have generous spirits. They do the best they can to let you into their world.

GS In “A Nail …,” you write a lot about the tsunami. Did you see the after-effects of it? Have you seen a difference, in Asia, since the tsunami?

TH I was in the USA when a tsunami hit Thailand, in December 2005. The first footage came from Phuket, the largest Thai island, about 450 miles south of Bangkok. As I watched the footage, I realized I knew exactly where the cameraperson stood. I knew what was behind it. I knew the names businesses, around the camera. It was as if I were there.

About four months later, I was back in Thailand. Almost everyone I knew lost a family member or friend to the tsunami. The aftermath was terrible.

Thailand depends on tourism. Tourists are magnets, for kids from poor families, and ripe to buy most anything. The country is terrifically poor. In the north, of Thailand, many families exist on $500 USD a year, compared with $47,000, for each person, in the USA and $86,000 in Qatar. The tsunami slowed tourism, to a crawl, for a long-time, and the effect doubled the disaster.

Hundreds of thousands of women and men depend on tourism. These women and men, who work in bars, rent bicycles or sell artwork, on the street, live off tourism. The tourist money also allows them to send money home, to help their families.

Many Thai won’t go to Phuket, any more. There’s a strong belief about ghosts haunting Phuket. In the Thai pantheon of ghosts, those who died violently, such as in Phuket, are most terrifying.

The Thai call these ghosts “hungry” or soul eaters. If able, hungry will eat your soul. The hungry leave only a husk.

GS The idea, of hungry, is scary.

TH My friend, Jim Newport, lives in Phuket, on the mountain. After the 2005 tsunami, he had no idea, whatever, about the extent of the damage. When he saw the damage, it floored him.

Newport drove into town, the afternoon the tsunami hit. He wanted to buy food, but there wasn’t a town. The town was gone. He worked for 36 hours, without stopping, trying to pull bodies out of collapsed buildings.

“For months afterward,” he says, “in every temple, in all over the island, the smell of incense was intense. People were trying, desperately, to put to rest the spirits of the people who died in the tsunami.”

There were rites going on 24 hours a day, in the temples. The Thai believe certain kinds of purification, certain kinds of acts of forgiveness or acts of gawd-speed eventually send the hungry away. “I could smell the incense, everywhere,” said Newport, “even up the mountain.”

GS Switching topics, can we talk about your inspiration for your central characters, Poke Rafferty, Rose and Miaow.

TH In 2001, I was in Bangkok for New Year’s Eve. I decided to walk the city during the night. I left my hotel about 11 pm, walking until I found a Starbucks at 9:00 am.

I went way, way, way off the beaten track, into areas of Bangkok that keep much of the character of little villages. Residents, of these areas, migrated from small villages to the slums of Bangkok. The families, of some of the women and men I saw, had known each other for generations.

Everyone invited me, a farang, to his or her party. The Thai are undoubtedly the sweetest, most generous people in the world. I thought how no one writes about the generosity of the Thai. Nobody writes about anything that’s outside the topiary version, of Thailand, which exists to impress tourists.

As I walked, I had a thought. A few minutes later, I had the idea for a book. The protagonist is a traveller and a writer.

He writes about rough travel. He focuses on going off the bright streets and avoiding tourist traps. His focus gives him a skill most writers don’t have: insight.

I imagined he had a few books in print. He’d been to the Philippines and Indonesia. Still, Thailand blind-sided him, the way it did me.

At 9 am, in Starbucks, I knew this character had a wife, Rose, who once was a bargirl. They adopt a street urchin. I like to write in coffeehouses and Miaow, the street urchin, comes from a young girl who’d sit by me as I wrote.

GS I find it interesting that many writers prefer to work in public places.

TH Yes or so it seems. When writing my first books, the Simeon Grist Series, I wrote in a little coffee shop called, “The Tip Top.” It’s a 24-hour coffee shop, in Patpong, where I wrote from about 4 pm until 10 pm, most days.

A little girl used to peer through the window, at me. She had a big cardboard box hanging around her neck, which was full of chewing gum she was selling. She riveted on the computer.

One afternoon, I brought her into the Tip Top and got her something to eat. When I took a break, from writing, I brought up a pinball game, on the computer. I showed her how work the flippers and play the game.

I went to the bathroom. When I can back, she was batting the pinball around like there was no tomorrow. You know, kids and computers are mystical. She’d never even seen a computer, but she could work it better, on instinct, than I could after learning.

She came by the Tip Top, twice a week, for a year. I’d buy all the gum she was selling. She’d play with the computer, when I wasn’t writing, and then go home.

One day she vanished. She stopped coming to the Tip Top, but I never stopped wondering about her. I wonder how she got to the Tip Top. I wondered why she was on the street and what happened to her? She became Miaow, with a Hollywood ending.

The description of Miaow is a physical description of that child. Miaow has a factual base. Rose, too, has a factual base.

GS Did you meet the archetype for Rose, in Patpong?

TH When I first went to Asia, I was a middle-class, white American. The first time I went to Patpong, the main red light distinct of Bangkok, was 1981. I thought, “Oh my god, a red light district.” My heart was pounding. I felt like Mr. Daring.

Patpong is the oldest, most garish of the red-light districts in Bangkok. There are bars, with dancers, in Patpong, and not much else. It gained fame during the Vietnam War, when American troops started going to Bangkok for rest and relaxation (R ‘n’ R).

I didn’t have the nerve to go into a brothel. Instead, I went to a restaurant. I had wonderful a meal. The server, a woman, was sweet to me. I left her 100 Baht tip. That’s a large tip, as it was only about 200 baht meal.

GS What would a Baht equal?

TH A Baht, then, was five cents: a five-dollar tip for a ten-dollar meal. After leaving this dingy, little restaurant, in the biggest red-light district, in Thailand, I’m halfway down the street and I hear somebody yelling. I turn around and the server is chasing me.

She’s waiving the Baht tip. She thinks I forgot it. I told her that it was her tip. She couldn’t believe it. She gave me a big Y (the hands together and the prayer), turned around and went back inside; she was ecstatic.

I thought, “This place isn’t as sleazy as I thought. If a waitress chases me when I leave money on the table, there's more to Thailand.”

All the people who worked in Patpong, all the young women who work in Patpong, are doing something, which from a Buddhist perspective, is admirable. They’re fulfilling a primary duty as children to take care of their parents and family. This is of major importance.

These young women are making merit, left and right, by sacrificing themselves. Sacrifice means they can send money home to momma and dad. This helps prevent younger sisters from having to come to Bangkok. It also keeps her younger male siblings in school. Overall, the family does better from her sacrifice.

GS Appears most admirable, but westerns likely don’t understand.

TH In Thailand, prostitution exists in a different emotional climate than it does in the USA. In the USA, prostitution is self-destructive. Drugs are a large part of prostitution, in the USA.

When I went to Patpong, there were no drugs at all. The young women didn’t smoke or drink, but, now, tattoos are as popular as speed. When I first went, the young women in Patpong were kids, 18 or 19-years old, and mostly not abusing substances.

These young women came from small, “two buffalo” towns to the big cities. They bought jewellery and cell phones, with the money they made. They also put their younger siblings through school.

After four or five years of working, in the big city, they went back home. Mom and dad had built a bigger house. The young women often married a bit higher than expected and didn’t carry a lifelong stigma, as in the USA.

A wonderful part of this form of Thai prostitution is the women are free. They can say, “No, I’m not going with you. You smell bad. You’re too drunk. I don’t like the way you look.”

They don’t need to give an excuse. They don’t have to go with anybody, as long as some money comes into the bar from drinks they encourage customers to buy. If a prostitute doesn’t like a bar, she moves to another one.

There are no pimps, in the bars. There’s no force. Thailand was a big education for me.

Rose came out of that background. As I said, the book I’m writing right now is about Rose. It’s about how she came to Bangkok. It’s about what happened to a young woman, from a village, when she got to the big city.

GS How did you learn, from observation or did you ask?

TH I spent much time in the bars. All the bar-workers want to speak English and are eager to practice. You can buy a soft drink, which costs about $2.50 USD, for three or four young women and talk with them for hours.

You can buy them lunch at noon. They’re delighted to have lunch bought for them. Then you can talk all day long. These are not secretive acts because there’s little shame involved.

Prostitution is always a second choice. They prefer not to do what goes on in hotel rooms. They accept the hotel rooms because they’re helping their parents and families. From a Buddhist perspective, the sacrifice, for others, removes any sin associated with an act. They don’t think about or see it in the Western sense.

GS How do they view it?

TH It’s what a young woman does to help her family. She likely doesn’t have other skills. There are some benefits to the big city, too.

In villages, the day ends when the sun goes down. Families huddle, during twilight and maybe candles burn, for a while. Everyone is asleep by 8:30 pm because it’s dark.

The next day, you lead the water buffalo around. Schooling stops after the fourth or sixth grade, depending on gender: males need more training for their job.

In the villages, you plant rice. You dig irrigation ditches. You work hard for little return.

Suddenly, a young woman is in a big city, where there are more people in the restaurant, across the street, than live in her village or town. She meets other young women who know how to apply cosmetics and dress up. Now, she’s wearing high-quality clothes, too.

She’s free, at least of the farm drudgery. She has one unpleasant duty. Yet, that duty earns her merit, in Buddhism, because it helps take care of her family.

When I first went to Thailand, there were no movie theatres. There wasn’t television in the north of Thailand, either. Today, the big cities are media and entertainment havens.

GS Is prostitution the only choice for migrants from the villages.

TH No, prostitution isn’t the only choice. When someone migrates from a village, they can work, for 12 hours a day, in a garment factory. Factories don’t use air-conditioning and the machinery is unsafe. The pay is low, about $3.50 a day, for a seven-day week.

Alternately, she can go to an air-condition bar or hotel, with a foreign visitor. There she earns $35 for half an hour. When you think about exploitation, you must consider the larger picture.

GS What’s your view? Is one choice worse?

TH I think both choices are exploitive. In Thailand, they don’t share our Judeo-Christian ideas about sex and guilt. The young women in the bars probably have a better time, make more money and help their families more. This is especially true now that everyone knows how to avoid HIV.

As well, Patpong is different, today, than when Rose arrived. The women are older, middle to late twenties and in the life longer. They make more money, too.

Around 4 pm, every day, there’s a bargirl at every computer, in the Internet Cafes. They’re firing-off e-mail after e-mail to men around the world. These men are sending the bargirl $500 or a $1000, each month, to keep her from having to work; they pay for her temporary virtue.

GS That’s an interesting variation on the oldest theme.

TH Each man, who gets an e-mail, believes he’s the only one. At 6 pm, the bargirls are with other men, who are paying them to say out, all-night. Some of these young women earn more than a middle level executive.

GS Why did you originally go to Bangkok?

TH I went by accident. I was working on a Public Television (PBS) series about the first tour of Japan by a western symphony orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic (LAP). I was on the road with the LAP. It was February. It was snowing. The tour was over.

I was going to visit the north, of Japan, to Hulkaido, to rest at a hot springs resort. I planned to sit in hot water, up to my nose, and watch the snowfall, while I read a classic Japanese novel, “The Tale of Genji.” This may be the first novel ever written.

I wanted solitude, after four weeks, of cramped quarters. My mistake was telling others about my idea. Suddenly, the string section, of the LAP, was joining me.

I called my travel agent in Los Angeles. I said, “Just book me someplace, here in Asia, where I don’t need a visa.” My choices were Thailand or Taiwan. Thailand struck me as more interesting.

When I deplaned, in Bangkok, the temperature was 97 degrees Fahrenheit. I was wearing earmuffs, a down jacket and mufflers. Halfway across the airport, I saw the immigration officers falling off their chairs, laughing at me. I think, “Well, this is different, I’ve never seen immigration laugh before.” After three days, I fell in love with the Thailand.

Yesterday, I wrote, for my next book, about Miaow playing Aerial, in a school version of “The Tempest.” She’s trying to transform herself and wants the kids, at school, to like her. What I wrote, yesterday, was about her drama teacher arriving in Thailand.

The teacher talks about what she first noticed in Thailand. She had a Korean reaction, seeing the Thai as lax, lazy and chaotic. Her face began to hurt from smiling too much.

This was my first reaction to Thailand, too. I returned smiles and my face muscles hurt. Then I grew curious about Buddhism because it made its followers happy.

About 97% of Thailand is Buddhist. Thais are among the happiest people, in the world. I was curious. I rented an apartment, deciding to stay on a while. I made friends. I return regularly to Thailand, but the first visit was an accident.

GS Do you stay in the same place when you go back to Thailand.

TH I stay at one of two or three hotels where I can leave some baggage, safely. The hotel stores my belongings and I move around freely. I do have an apartment in Phnompenh, Cambodia.

GS I have a typical Western reaction to Phnompenh: “M*A*S*H.” Everyone, from the “4077,” went to Phnompenh for R ‘n’ R.

TH These days, I do most of my writing in Phnompenh. Bangkok is distracting, whereas Phnompenh is boring. When I need to write, distractions and excitement are less attractive.

GS Can we talk about your life before you started writing full-time.

TH I was a principal in Stone Hallinan, the biggest television-based public relations and consulting firm, in the world. That was a long-time ago. The Stone Hallinan client list included many “Fortune Top 50” companies, such as IBM, General Motors, Xerox, Exxon Mobile, Ford and Hallmark.

Our job was to help these companies decide which television shows to sponsor. Each company had a target audience. Each television show had a target audience. Stone Hallinan made matches.

Stone Hallinan also represented the PBS, in the USA, and the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), in the UK. Overtime, we became involved only in quality television. Stone Hallinan didn’t do network series. We didn’t do junk. Stone Hallinan did television that at least tried to be serious.

I began to think there was much television programming that could be useful to teachers, if they had a way to know about it and materials to use. I started a company, Hallinan Consulting, which got IBM, General Motors or Xerox, for example, to fund free teaching materials related to shows each company supported. I sent the materials to teachers across the country, free of change, which was novel.

When the Internet came along, I figured, “Why am I spending all this money on printing and postage. I put the all the materials online. We created extraordinary websites for teachers. PBS ran a six-hour series on slavery in the USA. We created a web site for teachers, full of relevant materials.

GS You helped many teachers. How and why did that come about?

TH Let’s take the example of Joseph Papp, in 1970. He produced wonderful version of “Much Ado About Nothing,” for Shakespeare in the Park, in New York City. If you want to teach Shakespearean comedy, “Much Ado …” is a superb play for teaching. Bringing the Papp production to television filled a huge void.

I went to IBM. I said, “It’ll take $350,000 to put together the ultimate Shakespearean comedy teaching package, themed on “Much Ado ….” IBM agreed, sponsored the PBS show and paid for the teaching materials.

We sent the package to English teachers, free. We asked the teachers to tell us what they thought, of the materials. We provided a small postage-paid card, in each package. Thousands of cards came back. Almost all the teachers said, “This is great, we loved it, we loved using it.”

Overtime, we did the same for the thirty-seven plays by Shakespeare. The BBC produced the television versions. Exxon, Metropolitan Life insurance and another company, which slips my mind, paid the costs. We did the same for the Ken Burns series on the USA Civil War.

In sum, useful, practical and free materials for teachers. A market for videos and DVDs, of these shows, was a corollary. PBS made money, which is rare.

GS Did you always want to write?

TH My whole life I wanted to write. I wrote my first six novels while I worked, full-time, at Stone Hallinan and Hallinan Consulting. I published six novels, writing from 6 pm until 1 am, most evenings. I love to write.

GS Why did you think that to write the Bangkok Series, you couldn’t continue to workday jobs?

TH There was no need to work two jobs. I got to a point in my life where I asked myself why I was doing anything except what I most wanted to do most, that is, to write. I couldn’t think of a reason. I didn’t need the money. My wife and I are not making anything like the money we used to make, but we don’t need as much, either. We’re fine

Why not write full-time. Why not give all my energy to becoming a better, happier writer. Having published books is not enough. I want to be a better writer. The best way to become a better a writer is not to do anything but write and that’s the origin of this experiment.

GS How is the experiment going?

TH I think it’s going well.

GS From what I’ve read, of your work, each book gets better.

TH That’s my hope. There are authors and readers who always like the first book, best. I can understand that because the energy around the characters was brand new, at that point. Among my books, I like “Breathing Water,” which released a day or two ago, the best of the Bangkok Series.

GS How does “Breathing Water” begin?

TH A 17-year-old young woman, “Da,” leaves her poverty-stricken village, running away to Bangkok, where she becomes a beggar. She doesn't know gangster syndicates control Bangkok beggars. Grabbed off the street, by gangsters, Da meets a top gangster, the boss of the street beggars. He sees her beauty and gives her a piece of pavement, from which to beg. For good measure, he gives her a baby, too. Women beggars, with babies, make more money than do those without babies. “Breathing Water” is about Da, her life and deepening attachment with the baby, whom she names Peep.

Da is at the bottom of the socio-economic scale, in Thailand. She seemed a good entry point. Through Da, I can delve into questions about how the corruption hurts the poor.

GS I understand why “Breathing Water” is your favourite, but maybe that’s a version of the first is the best; the latest is the best.

TH Maybe, but in “Breathing Water,” I was successful in presenting an honestly wide range of characters. The goal was to bring the elite into direct conflict with the lowest of the low. Who is lower than is a beggar? Lower than a beggar is the stolen baby she must hold in the street. The baby creates sympathy and passers-by give her more money. Intentionally, this book contains a full range of characters along the axis of wealth and power.

The inspiration, for “Breathing Water,” is the current mayhem in Thailand. Although the mayhem remains below the surface, it may lead to the end of the Kingdom of Thailand. When Thaksin Shinowatra, the Prime Minister of Thailand from 2001 to 2006, extended the vote, he irrevocably changed Thailand.

GS Didn’t Shinowatra win by pandering-for or buying votes.

TH Well, yes, Shinowatra won by spending millions. He was the richest man in Thailand. He was not a member of the power elite. He was a successful entrepreneur.

Shinawatra became prime minister buying votes in the north and northeast, the poorest parts of Thailand. He succeeded beyond his wildest dreams. He’s the only prime minister, in the history of Thailand, elected by majority vote, in the highest voter turnout in Thai history.

GS He’s the only Thai Prime Minister to complete a full term.

TH Yes, every other prime minister had to work with a coalition. Shinawatra won more than half the popular vote. What he lacked was any support from the establishment.

Those who run Thailand have done so for 250 years; they built Bangkok, in the 1760s. The power elite disliked Shinowatra. He wasn’t a member of their club. He didn’t want to be a member, of their club. That may have been the source of his downfall.

The corruption, in Thailand, is staggering: hundreds of billions of dollars a year. A major concern is who gets to dip their scoop into the corruption pool. The elite, who scooped for 250 years, didn’t allow Shinowatra to the pool. They ousted him from office and the country.

In the next election, the poor, in the north and northeast, realized their votes counted. They elected an alternative version of Shinowatra. In fact, Shinowatra, himself, placed second, in the voting.

To make a long short, short, the elite bribed seven Shinowatra supporters, members of the assembly his cabinet, to change sides. Today, the elite have a tiny majority, in the Thai legislature. In the next national election, the elite may lose, badly. Every Thai knows what the elite did. You can’t put toothpaste back in the tube.

In the middle, of the mess, is Bhumibol Adulyadej, the 81-year old King of Thailand and Head of State. He’s the longest-serving Head of State, today, and the longest reigning King of Thailand. Adulyadej took office on 9 June 1946.

The King is the primary stabilizing force in Thailand, today. When he passes, no one knows what will happen. Someone, much like the character, Pan, in “Breathing Water,” may eventually replace Shinawatra.

GS About “Breathing Water,” wasn’t the original title “Misdirection”?

TH That’s right.

GS Why did you change the title?

TH Nobody liked “Misdirection.” I have yet to devise a title the people at William Morrow, my publisher, like. Most of my published titles are third or fourth choices.

I think “Breathing Water” has much in its favour. The word combination is interesting. There’s one other book, with the same title, but it’s a collection of short stories. I came to believe “Breathing Water” fit the Poke Rafferty character.

I wrote a long scene, with Poke and Arthit, his friend and a police officer, in a coffee house. Arthit gives Rafferty the dummies guide to the revolution. The point of the scene is to make the title work.

GS Titles seem a problem for all authors.

TH True, a dozen may have the same title. There’s no copyright protection for a title. That’s part of the challenge.

GS Switching topics, “The Fourth Watcher” was your second book in the Bangkok Series. Can you give us an idea of its central theme?

TH Poke is about to let his series of travel books end. His lifestyle, which arises from his books, is too dangerous. He wants to settle down, with Rose and Miaow. Then a character, which Poke prefers not re-enter his life, appears. Gangsters, from Chine, are after this new character. As well, Rose finds she’s involved in a North Korean forging scheme, without knowing it. “The Fourth Watcher” is a mess for Poke to resolve.

GS The character, on the run from Chinese gangsters is the father of Poke. Is this more of an autobiography? I read your father travelled Asia and had and Asian heart.

TH The story about his father going to China, never talking about his experience or eating Chinese Food is my father, a little bit. For her entire life, my mother believed my father had a family in China. We don’t know if it’s true or not.

The elder Rafferty is not my father. He’s vile and my father was a gentle person, in all ways. Poke and his father are relevant because my books are as much about adventure as family.

What I thought interesting was what might happen when a father destroys the family of his son and reappears after the son has built another family. This was my goal when I began “The Fourth Watcher.” I knew the elder Rafferty would come out of China, when I began. His half-sister, Colonel Chu and the other characters developed as I wrote the story.

GS What did your father do, for a living?

TH My father was in business. My mother kept house. I have two siblings, Michael, a painter, and Patrick, an illustrator of books for children.

We’re fifth-generation in Los Angeles. My maternal relatives settled in LA in the 1880s. We still have a Homestead, of land, near Bakersfield. Poke Rafferty had to grow up somewhere, so I based him in Lancaster, California, near Bakersfield.

GS Writers decide. The ethnicity, of Rafferty, is an interesting decision. Why did you decide to make him a mix?

TH Rafferty is half Filipino. I did it for an unpublished book: “Bangkok Tango.” This was the first book in the Bangkok Series, which I wrote to get to know the characters. I didn’t expect “Bangkok Tango” to find a publisher and it remains unpublished.

In “Bangkok Tango,” someone frames Rafferty for the murder of a Bangkok police office. He must blend into the city. If he’s half Filipino, he blends more easily on the streets of Bangkok. As I developed Rafferty, I realized his yellow heart” makes more sense if it is part genetic, not only emotional and intellectual.

GS Do you think Rafferty, as half Filipino, affects your chances for movie or television versions of the Bangkok Series.

TH Yes and no, it depends on casting. For a while, a top actor, a major figure in Hollywood, optioned the Bangkok Series. He wanted to portray Rafferty. The actor sells many movie tickets, but is archetypically Anglo; he would destroy the character appeal. I was all right when the deal fell through.

GS What actor do you imagine portraying Rafferty, in a movie, effectively?

TH Johnny Depp, who’s not Asian, but his ethnicity, Native American and Portuguese, make him the ideal choice. I think it’s important for Poke to look different. Readers and editors think Poke is half-Asian. This idea may work, may save his life, in another book, but not in the current or next book.

GS Is the Bangkok Series finite. Do you intend to keep going?

TH As long as there’s a market, for the Bangkok Series, I’ll keep it going. There are so many stories to tell, about Rafferty, Rose, Miaow and the other characters. The problem, for the Bangkok Series, is Miaow, a child, who must grow up, with time.

GS A child grow up may offer opportunities and challenges.

TH That’s true, in “Breathing Water,” a character returns from “A Nail …” that helps show how Miaow develops. I needed a way to dramatize her transition from street urchin to a middle-class child, of ten or eleven years old. As I developed this part, of the story, I realized no one sees the urchins. Rafferty needs an army to survive his dilemma. What better than Rafferty engages the invisible street kids?

GS Conan Doyle comes to the rescue. Did you foresee that character coming back or not?

TH No, but I’ve never had more reaction to anything I’ve written than to how that character ended in “A Nail ….” I probably got 300 letters and emails from people stressed out by the way the story of that characters ends. Every one hated it.

GS Yes, I, too, thought the end of that character surprising.

TH My editor tried to get me to change it. I couldn’t. A “happy ending” was impossible for that character, in that book. I didn’t want to do a Hallmark or Hollywood, in this series.

I had no idea he’d come back. I’m glad he was available when I needed him. It’s funny that when I needed him he was there.

GS In “Breathing Water,” a principal character dies. Did you plan that event? Did it merely happen?

TH I knew I was going to do away with this character when I started the book. I knew from the beginning, of the Bangkok Series, this character would disappear. The Series will lose another character, down the road.

What I like to do is declare no bets are off. Everything is on the table, as in real life. These are not cozies. This is not a safe world, where everybody we like always does well.

Now, I’m dealing with how not to give away the death, of this character, for people who read the Bangkok Series out of order. This is a major concern, needing much caution.

It’s a difficult line to walk. I don’t want to annoy readers, so they don’t return. At the same time, this world has authenticity, in my mind, which has nothing to do with me managing it.

Rafferty runs into some trouble and I don’t know how to help him. Then a new character tugs at his shirt. I had no idea she’d appear in the story. She appeared, suddenly and naturally.

She’s going to be important to the story. I wrote as fast as I could. I’m not controlling what’s happening.

GS That’s interesting. How do you explain such uncontrollable?

TH A friend, Rob Royer, once suggested a great metaphor for these uncontrollable appearances. Royer is a songwriter and musician, a one-time member of “Bread.” He co-wrote, “For All We Know,” with Jim Griffin. “The Carpenters” recorded the song, which won the 1970 Oscar� for Song of the Year.

When Royer writes, he claims, he isn’t an architect, but an archaeologist. He’s not building anything new, but slowly uncovering what exists.

GS That’s a great metaphor.

TH Yes and I feel like the world, of the Bangkok Series, is in my mind, complete and going on even when I’m not paying attention. My job is to reveal that world, with enough care, that I don’t break it or force it into shapes it doesn’t want to form.

There will always be a story in or about that world. As I said, writing is a precarious line of work because you’re flying on faith. The faith is the story exists; I can find it and tell it to the reader.

I discover a world, a new part of a world, with each book. Yes, I discover, I don’t make up the world. I report on that world.

I watch events unfold as I write, I witness. In one scene, in the next book, “The Rock,” Rafferty runs into the side of a moving car when he’s chasing someone on foot. Now, he's standing outside the building where his prey hides. His elbow perhaps broken, it hurts, a lot. What’s he going to do? I have no idea.

Nursing his elbow, on the street, a young child, a girl, tugs at his shirt. Rafferty, in fright, whirls around. She stumbles and sprains her ankle. I watch this happen.

Sounds a bit insane, I know, but all writers talk about their work in much the same way. We’re journalists or archaeologists. When we attach meaning, to what we witness, we’re sociologists.

GS When you write you listen to music. You point out what music influenced you, at the end of each book. How does music help you write?

TH It’s energy. Music is an energy source. As I like to write in public places, I like having the energy of people around me. It helps keep me from distraction.

If I write in a coffee shop and someone drops a plate, I don’t hear it. I’m with the music. Mainly music is an energy source. I have about 6000 songs on my iPod, which is one of my most valued possessions.

GS Does any singer or musician give you more energy than do others?

TH Yes, Van Morrison, I’d miss his music, most, if I lost my iPod. When I listen to music, especially Morrison, it keeps my energy up. For some scenes, I change the music. In “A Nail …,” when Rafferty proposes to Rose, that scene called for different music.

GS Tom Petty talks about strangers approaching him and saying, “Thanks for providing the soundtrack of my life.” Does your iPod provide the soundtrack for your stories?

TH Yes, but I hadn’t thought of it that way, exactly.

GS Do you use the shuffle, so different songs play. Do you prefer hear certain songs you want those certain scenes to come up?

TH I have about 15 playlists. Some of the playlists are 50 songs and some are 750 songs. My playlists, no matter the length, share certain characteristics.

If I’m writing a long scene, such as an interior monologue, which has tender feelings and such, I listen to a playlist that has “Vienna Teng,” “The Fray” and other piano-based rock. For a different scene, I use a different playlist. I like to think I define my playlists by emotion.

The minute I download a new song, I know the list it’s joining. If I get music from a web site, I know before loaded where it’s going. I think the ability to get music from the web is a gift from gawd to music lovers.

GS You mention your wife, often, can you talk about her a bit.

TH Her name is Munyin and her last name is Choy, C-h-o-y. Koreans spell the name Choi. Every Korean, to whom I introduce Munyin, thinks she’s Korean, not Chinese.

We met at UCLA. I was a guest speaker, in a public relations class. I saw her, in the class and thought, “Wow!” We married.

Munyin is my first reader, my first audience. Before I send a book to an editor, I read it, aloud, to Munyin. She lets me know if the story follows and flows, is understandable and interesting. If Munyin says the story is all right, I’m more confident sending it an editor.

Sometimes, she falls asleep, as I’m reading. This tells me the story needs more work. She’s hugely valuable and I thank gawd for her.

I probably learn as much, reading the book aloud, to Munyin, as I do from any part of editing. It’s necessary to read your writing aloud, to someone else. It’s as if there’s a rope between reader and writer. If the rope slackens, the writing has weakened. If the rope tightens, the story and writing are on mark.

The first time I read “Breathing Water” to Munyin, she didn’t like it. The story was hard to follow and too complicated. There were too many characters, with confusing names. I was in despair.

GS What did you do?

TH I rewrote the entire book, of 130,000 words. When I read the new version, she thought it was fifty per cent better. I rewrote and changed until Munyin and I agreed it was good to send the manuscript off.

GS You’re a better writer for the rewrites.

TH Yes and I also find it useful, when I write, to imagine I’m telling the story to someone. This helps keep the language simple and the storyline intact. Munyin is the person to whom I imagine I’m telling the story as I write.

GS I think you mentioned another series, of books, you had in mind.

TH I’m talking, with publishers, now, for a series about Junior Bender. He’s a crook, who lives in San Fernando Valley. The twist is Bender is a private eye for crooks.

If someone steals from a crook, there’s no police involvement. The crook, the victim, turns to Bender, who solves crimes among crooks. “Bad Money” is the title of the first book in the series.

Bender is different from Rafferty. He’s divorced. He has a 14-year-old daughter, Rena.

This Bender Series is funny. Each book moves along fast. The Bender books are shorter than in the Bangkok Series, too.

GS Readers probably think Rafferty is easiest to write, since he is also a writer.

TH Poke Rafferty is reasonably interesting and fun to write. I also find Miaow easy to write, by far.

When I write about Rafferty or any protagonist, I know the reader is with him, us, for 325 pages. I have to hold back, slowly leaking information about him. This holds reader interest and is the way life works: we slowly leak information about ourselves to others.

Writing the other characters, I throw all I can into a scene. These characters come and go, in any book. I have to write about them as I can, when I get the chance

Poke is front and centre, for the whole book, but not at full volume all the time. Miaow, for example, might have nine scenes in a book. She has to go full volume, for her few scenes, otherwise readers can’t empathize with her.

Readers expect and understand this style. I slowly leak much about the main character. I quickly write much about other characters.

GS You write series, do you think, when you write, this is a series, I can cover this or that in the next book.

TH I don’t know. I like series. I like reading the book, knowing there are five or six more, coming. I like the challenge of creating a character and taking him or her through eight or ten stories.

It’s less work, I think, to write a series. I don’t have to invent a hero or cram all my ideas into one, stand-alone book. New facts, about characters, pop-up in every new book and the period is long.

My favourite novel, “The Pallisers,” by Anthony Trollope, is six volumes. Is that not a series? Trollope writes about an arranged marriage; how the newly-weds can’t stand each other, but grow into one of the greatest love stories in English fiction.

When I finished reading, “Can You Forgive Her,” the first volume, of “The Pallisers,” I thought, “Five more books to read.” It elated me, as if I had a million dollars in the bank. I couldn’t believe the joy.

I felt the same joy when I discovered Phillip Marlow, created by Raymond Chandler, and knew there were five or six novels in that series. My editor wants me to write a stand-alone, but I’m not sure. The temptation, to write a stand-alone, is strong: only a few book series, such as Lee Child, Patricia Cornwall or Robert B. Parker, make the best-sellers lists.

GS Will you succumb to the temptation to write a stand-alone novel?

TH What I want to do, right now, is the story of Poke. I also want to explore Junior Bender: I love the idea of crooks in the San Fernando Valley. For me it’s an exotic environment.

GS Your first series focused on Simeon Grist. Can you give us a brief idea of the central theme of those books?

TH Simeon Grist, a thirtyish, hip private eye, in Los Angeles, knows the city as the back of his hand. He knows about the prostitution and the pimps and South Central; the chic seductiveness of the endless availability of drugs, parties and perversions; the client list at every bar from Hollywood and Vine to Venice. At least he believes he does.

Grist gets around, but not as he imagines it. His home overlooks Topanga Canyon and he drives a clunker, called “Alice.” Grist is prone to mild substance abuse and too much introspection; he’s not the tough, unflappable truth-seeker of his self-image, more than is Marlowe.

The first book, in the Grist Series, was "The Four Last Things," in 1989. The last installment, in 1995, was "The Bone Polisher." Four other books appeared in that series, "Everything but the Sequel," in 1990; "Skin Deep," in 1991; "Incinerator," in 1992 and "The Man with No Time," in 1993.

GS You were busy, those years, especially since you were working Stone Hallinan and Hallinan Consulting.

TH Yes, but, as I said earlier, if you can write every day, it's possible to work, write and publish. It's not easy to do. This is why many writers give up and stick with the sure-money provided by their day job.

GS Has the Grist series ended.

TH I thought Grist had run its course, but, in the last few days, there’s renewed interest. A publisher wants to reprint the series, with introductions by other writers. I hope it happens, but I’m sure I couldn’t write another book, in that series.

Grist reflected who I was when I wrote about him. That was a long-time ago; the last book, in that series, published in 1996. I’m no longer that person.

Today, I like the ambiguity of Poke and Bangkok. I like the moral landscape, which is more equivocal. In Bangkok, what the women and men have at stake are the basic needs, of life, not luxuries and wants.

Bangkok is a wonderful place for me, in my mind and on the ground. I’m going to keep writing the Bangkok Series, for a while. I have a long way to go.

Junior Bender has issues I want to explore. He’s a challenging character, solving crimes against criminals by criminals. Bender holds my interest, tightly.

Rafferty and Bender need a series to satisfy me. This adds to the difficulty of writing a stand-alone novel. I think my characters are more complex than one novel can develop.

GS Who are you’re favourite writers?

TH I read everything. I mean I read everything. In thrillers, I like Lee Childs and Brett Battles whose third book, “Gone Tomorrow,” just came out; I think he’s a great writer.

I think the best American mystery writer was Raymond Chandler. He invented the entire style. Chandler usually gave the credit to Dashiell Hammett, though.

Both Chandler and Hammett came from “Black Mask,” the magazine that birthed hard-boiled thriller and mystery fiction, in the 1920s. Earle Stanley Gardner, who wrote “Perry Mason,” and John D. MacDonald, who wrote Travis McGee, also started with “Black Mask.”

Chandler had the most wonderful description of Hammett. He said, “Hammett gave murder back to the kind of people who commit it.” It’s a priceless line.

I don’t only admire Raymond Chandler as a mystery writer. He’s my favourite writer about writing. When I read the Chandler letters, which are widely available, I learned more about the basics of writing. He generously wrote about how he wrote, what worked for him and so forth.

GS Do you have one favourite novel?

TH My favourite American novel is the “The Recognitions,” by William Gaddis. When I was in college, I happened on it. “The Recognitions” published in the 1950s. The book is 900 pages, without a single quotation mark.

“Recognitions” is about forgery in every regard: art forgery, medieval forgery, personality forgery, spiritual forgery and so forth. I educated myself using “Recognitions,” for about three or four years. I learned about Flemish painting, the Jewish Diaspora, all sorts of ideas and events.

Among current writers, of thrillers, I think Bret Battles is the best. His three novels are superb.

GS Does he know that you think he’s a great writer?

TH Yes, I told him when we met at “Thriller Fest,” in New York City. He’s disgusting, in a good way, only 35 years old or something. Nobody should write a good book until at least 50-years old.

GS Right and you’re a great advertisement for that philosophy.

TH Somebody like Tom Rob Smith, who’s probably eleven years old, comes along and writes “Child Forty-Four.” I mean it’s not fair. Smith should’ve written a few bad books, first, as I did. Everybody should write three or four bad ones first. My first three novels were horrible.

GS Finally, I’d like to talk about your blog, the “Blog Cabin.” What a help for writers or anyone trying to write a book or short story. You and others offer much good advice, for writers, on that blog. What gave you the idea to make “Blog Cabin” more than a promotional site for your books, but as a helpful tool for writers?

TH Well, I think any web site that doesn’t bring value to those who use it is a waste of bandwidth.

GS If true, several million web sites will shut down, this moment.

TH I couldn’t create a web site solely for self-promotion, “Gosh, I’m terrific. Here’s my book. Buy it.” It’s not me. Why would anybody want to build such a site? Why would I want to waste my time doing it?

The web site is an opportunity for me. There’s discussion of my work. Most important, to me, are the “Finishing Your Novel” pages. I try to help others write and improve my writing.

For years, I taught a class called, “Finishing Your Novel.” It was mostly for adult writers, who wanted to work in long form, such as memoir, non-fiction or whatever. The challenge is the same as for a novel.

I put the information I used in the course on the “Finishing Your Novel” pages. I added what I learned from my students and my writing experiences. Three recently published books give credit to this part of my website.

GS You have an intriguing story about the writer, Leon Uris.

TH A long-time ago, I met Leon Uris. He was a top writer in the 1950s and 1960s. Uris wrote “Exodus.” Most of his books were 800 pages long.

When he finished a book, he performed the bravest act, of any writer, ever. Uris took his manuscript, turned it upside-down, so the blank side of the page was up. He’d count, from the left side of the typewriter.

He’d go, one, two, three, moving page to the right-hand side. The fourth page he’d crumple up four and toss in the wastebasket. Then five, six, seven and page eight would go to the wastebasket. He gave himself one paragraph to link the missing pages.

GS This sounds as a version of the Rudolph Flesch writing technique. Flesch advised writers to remove every second word, from their text, replacing only necessary words.

TH Uris cut a manuscript by 25%, without reading a word. What nerve does that take? His method meant that if his darl ing phrase or sentence was on the crumpled page, he lost his darling.

I learned so much from meeting. Uris was an exceptional person. I don’t know anyone as gutsy as him.

GS Thank you, Tim.

-----

Click here to read a review essay, "Rainy Nights in Bangkok."

Click on title, below, to read a review of other books by Timothy Hallinan

Crashed, the first book in the Junior Bender series.

The Fear Artist, a Poke Rafferty thriller set in Bangkok.

Fourth Watcher, a Poke Rafferty thriller set in Bangkok.

Breathing Water, a Poke Rafferty thriller set in Bangkok.

Nail Through the Heart, a Poke Rafferty thriller set in Bangkok.

Queen of Patpong, a Poke Rafferty thriller set in Bangkok.

Click here to buy books by Tim Hallinan

*Shadoe Stevens is a regular on "The Late, Late Show, with Craig Ferguson."

Click here for a list of all Grub Street Interviews.

Interview edited and condensed for publication.

Rich Knight teaches English, in Dover, NJ.

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- Bacteria and Greece

- Valises

- The Special Christmas

- Sjef Frenken

- Dog Heaven

- Je Regrette

- Jack the Poet, Redux

- Jennifer Flaten

- Gardening 2011

- A Parrot on a Leash

- School's Out, Forever

- M Alan Roberts

- Fit to Survive

- Seasonal Musings

- Health is Wrong Here

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Time to Chill

- Top DJs Part 1

- Whither the Idol

- Streeter Click

- Social Effects of COVID

- Orhan Pamuk

- Grub Street Philosophy: 2

- JR Hafer

- Scott Muni

- Why and Wherefore

- Fantasy of Flight

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- Pennies on a Rail

- Top Three GOP Sins

- The Queen is Back

- Jane Doe

- Recovery Redux

- A Coffee Mug

- Argo

- M Adam Roberts

- Nick the Busker

- A Father's Heart

- One More Round

- Ricardo Teixeira

- Harmony

- There is a Light

- Monkey Business